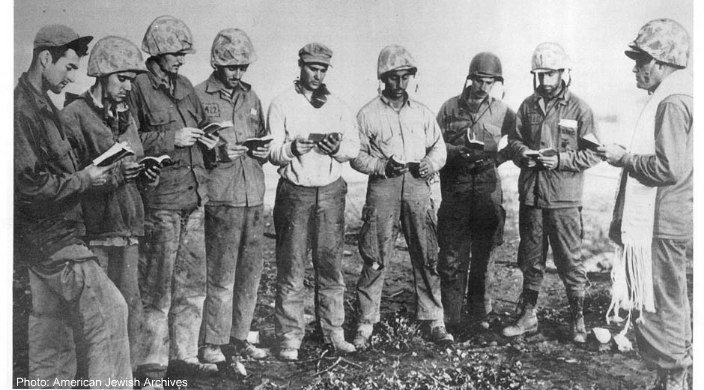

Photo: Rabbi Roland B. Gittelsohn conducting a Jewish service on Iwo Jima, from the Jewish Archives

From conversion-related controversy to conflicts over access to the Kotel, it seems nary a news cycle in the life of the Jewish people passes without a story about intra-Jewish conflict. However, far less discussed are documented instances of intra-Jewish cooperation, particularly those in which Reform rabbis had leading roles in bringing the Jewish world – in its totality – closer together.

One such moment arose during World War II, when American rabbis of all denominations banded together to meet the religious needs of the more than 500,000 Jews serving in the U.S. armed forces. Spearheaded by the Committee on Army and Navy Religious Activities (CANRA), under the auspices of the National Jewish Welfare Board, this effort recruited hundreds of American rabbis from across the ideological spectrum. Although most of America’s Jewish soldiers came from religiously traditional backgrounds, it was two Reform rabbis who supervised much of CANRA’s work: Rabbi Philip S. Bernstein, its executive director from 1942 to 1946 and Chaplain Aryeh Lev, the liaison between CANRA and the U.S. military, who also compiled military chaplaincy records consulted for this article.

Although religious observance in the midst of global war varied according to time and place, ensuring the ways and means of Jewish religious practice was the chaplains’ primary mission, regardless of ideology. This was not such a simple task given the complexity and range of Jewish practice within American Judaism, requiring chaplains to serve Jewish combatants regardless of denomination, theology, or practice. Under the guidance of Bernstein and Lev, most of the chaplains succeeded in developing a broad, inclusive system of Jewish practice for the soldiers they served.

In describing the responsibility, however, Bernstein downplayed the challenge of bringing the Jewish community together:

“We do our best to interpret the concern of the total Jewish community, the chaplains on the one hand, and to explain the realities of military life to civilian religious leadership on the other. This is far from an easy job and I presume no one is ever completely satisfied.”

Despite their small numbers, some American rabbis took a more sectarian stance and attempted to circumvent CANRA, appealing to the U.S. government directly. For example, several such rabbis protested to the U.S. Army Chief of Chaplains that “Reform and Conservative are by no means regarded…as rabbis in the true sense...”

Moreover, throughout the war Bernstein and Lev, alongside Conservative and Orthodox colleagues, faced personal attacks on their religious authenticity. In one missive, a correspondent claimed that Lev, was a “preacher of the Reform sect and therefore hardly the one” to make decisions about Jewish practice, objecting that “crude Reform agents” and “irreligious, ignorant, disloyal ‘Conservatives’” were imposing their “mongrel ‘services’” upon Jews in the armed forces.”

And yet, except in a handful of cases, the reality proved otherwise. As one leading Orthodox rabbi reported “I found some Reformed [sic] chaplains not only thoroughly sympathetic, but truly enthusiastic about the Orthodox men.” In another case, an observant soldier, who happened to hail from one of the most prominent, Orthodox rabbinical families, defended a Reform chaplain against charges of being unresponsive to needs of traditional Jews. The soldier asserted in an internal memo that the Reform chaplain not only provided observant soldiers “his greatest cooperation,” but also that “through him and on account of him, I was able to keep up the Jewish Orthodox way of life I was used to.”

At the same time, there were Reform rabbis who struggled to serve more traditional Jews. As Bernstein wrote privately to one frustrated chaplain “…when a rabbi becomes a chaplain, he is not an Orthodox, Conservative, or Reform chaplain, but a Jewish chaplain serving the needs of all the Jewish men.” Writing to another Reform rabbi struggling with traditional practice, Bernstein explained it was:

“imperative for all of us to make adjustments so that we may find common denominators which, of course, will not be entirely satisfactory to all.... For you or me to cover our heads in prayer involves no serious compromise or sacrifice. But for these Orthodox rabbis…to be compelled to ride on Shabbos and to eat army food is a heartbreaking experience…But on the whole and with rare exceptions, they have fulfilled their promises to CANRA to set the needs of the men in uniform above their personal religious predilections...”

Later, reflecting upon his chaplaincy, one Conservative rabbi recounted that regardless of denomination, the rabbi chaplains:

“were themselves brought closer together by virtue of their Army experience...We shared common hopes and anxieties about the Jewish community on the outside, our religious schools, laity, the plight of our people in Europe, Zionism, etc. It is unfortunate that much of this solidarity could not have been carried over into our civilian congregations.”

Though it is irrefutable that a confluence of unique circumstances fostered such exceptional intra-Jewish cooperation, our tradition has long recognized that there are both constructive and destructive ways to express differences. In the classic rabbinic text, Pirkei Avot (Chapters of the Fathers), the sages – no strangers to intra-Jewish conflict – addressed communal disagreement directly, distinguishing arguments conducted “for the sake of heaven” from those that were gratuitous rancor, teaching that the former have enduring value. Although communal controversy may be endemic to Jewish life, may all of us, in the spirit of the sages, always endeavor to conduct ourselves “for the sake of heaven.”

Photo: Rabbi Roland B. Gittelsohn conducting a Jewish service on Iwo Jima. Courtesy of the American Jewish Archives.