Ruth the Moabite said to Naomi, “I would like to go to the fields and glean

among the ears of grain, behind someone who may show me kindness.”

“Yes, daughter, go,” she replied.

-- Ruth 2:2

It was summer 2014, and Israel was at war. Tourists were sparse and so were volunteers. I was in a field outside Rehovot, picking daloriyot (butternut squash) alongside a dozen other visitors. And I was thinking of Ruth the Moabite.

In the Book of Ruth, which is read on Shavuot, Ruth and Naomi return to Bethlehem from their tragic sojourn in Moab, and Ruth goes to the fields to collect grain for herself and her mother-in-law. Leviticus (19:9-10 and 23:22) and Deuteronomy (24:19) state that the gleanings of the field belong to people who are poor, immigrants, orphans, or widows – and Ruth belongs to at least three of these categories. As a Moabite woman, whose husband died and who has arrived empty-handed in Bethlehem, Ruth is among the most vulnerable people in the land.

The Torah created a radical framework for supporting people like Ruth and Naomi. At a time when wealth was synonymous with land, animals, and crops, the Torah stipulated that a certain part of your fields didn’t belong to you at all, but to people who were in desperate need. What’s more, they were entitled to come and take what was rightfully theirs. These parts of the field were called:

- Pe’ah: the corners of the fields;

- Leket: gleanings that were dropped by those harvesting the field, or were missed the first time around;

- Shikhecha: parts of the field the farmer forgot to harvest.

Rabbinic tradition later transformed these precepts into the laws of tzedakah (using money to do the work of world-repair or, literally, justice).

Early Zionist pioneers came to Israel with a passion to renew the traditions of the people and its land. Rav Kook, the 20th-century Zionist mystic, believed Zionism would renew long-dormant agricultural practices. In 1909 he wrote, “Our spirits are lifted by what we can fulfill of the Mitzvot [commandments] that are connected to the land, even though what we have is still only partial. Now is the time to revive those aspects of the Torah that speak precisely to the revival of the Land.”

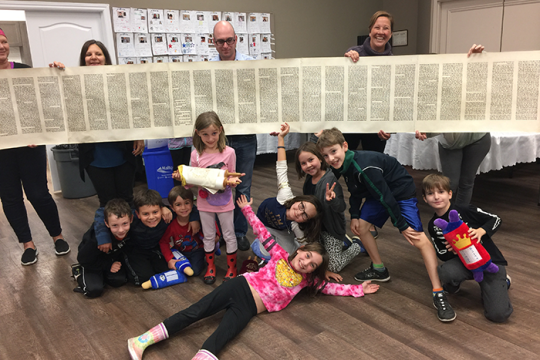

This renewal of Jewish life is happening now, all throughout Israel. Surely the connection between working the land and the Torah’s provisions for the neediest people in our midst should be part of our own Zionist vision. True to Rav Kook’s spirit, leket is alive and well in Israel. My daloriyot harvest was with Leket Israel, the country’s largest food rescue network. Their workers and volunteers glean vegetables in the fields and deliver them to hundreds of anti-hunger organizations around the country.

Modern farming techniques make it financially impractical to revisit every field after the first round of crops has been gathered – which is how I found myself in a squash pasture. The plants had already been picked over once, but plenty remained on the vine; fresh food that would rot if we gleaners didn’t get to it soon. We went to work—a three thousand-year-old echo of Ruth gleaning the leket in fields just a few dozen miles away.

I developed a rhythm. I would identify a ripe squash, snap it from its stem, put it in my basket, and move on to the next one. The sun was hot; the field went on forever. I got very into it, losing myself to the cadence of the harvest. The hours flew by. I looked to the bin that I had been filling and the volunteer coordinator considered my progress.

“You’ve gleaned 400 kilos,” she told me, “Enough to feed 100 people.”

But the fields are so big, and there is so much left that inevitably will rot on the vine if left unpicked.

There also are too many modern-day Ruths and Naomis. We justifiably celebrate the astonishing high-tech culture of modern Israel; it is one of the strongest and most dynamic economies in the world. Yet there are far too many who are left behind. Israel (along with the United States) has one of the largest income gaps between rich and poor in the western world, with one in three children living in poverty. This statistic is hardly the Torah’s standard of economic justice or the egalitarian vision of the early Zionists.

As we hear the story of Ruth on Shavuot, lovers of Zion must ensure that the Torah’s voice of compassion and economic justice speaks in Israel (and in our own communities) today, and that every would-be gleaner has the support she needs to survive and to climb out of poverty.