Decorate your Sukkot table with Ethiopian, North African, and Sephardi breads full of fall colors and tantalizing spice mixes while broaden your palate with the customs of Jewish communities around the world. Laden with seasonal honey, pumpkin, or orange, these breads don’t need braiding and make perfect gifts.

1. Orange Flavored North African Boulou (pareve/no dairy)

Throughout the Hebrew month of Tishrei, Jews from North Africa enjoy this orange-scented boulou bread. Boulou is also called "pandericas," "mounas," and "petit pain." It is a citrusy and golden addition to any Sukkot spread.

Sephardi and North African Jews were among the first Jews to experience oranges when they were brought through North Africa to Spain near the end of the 9th century. Jews contributed to early citrus businesses as distributers and wholesalers. Ashkenazi Jews peddled oranges in Europe and England. Israel’s Jaffa oranges were a big business for a good part of the 20th century.

2. Honeyed Ethiopian Yemarina Yewotet Dabo (dairy)

On the , the dough for this Ethiopian bread is doused with honey and the slices are drenched with more honey. Initially baked in a clay-covered pot lined with banana leaves over embers, this dabo bread is enriched with butter and milk, as reflected in its Amharic name: yemar = honey; yewotet = milk; dabo = bread. Some Ethiopians believe that bee honey was one of the many gifts that the Queen of Sheba brought to King Solomon (II Chronicles 9:1).

The focus on honey in this tasty loaf makes sense, given that Ethiopia’s honey manifests regional subtleties from its biodiversity. This includes a highly valued white honey derived from sage plants in the Tigray region. Honey also forms the base of the national fermented honey wine, tej, and the related honey water, birz.

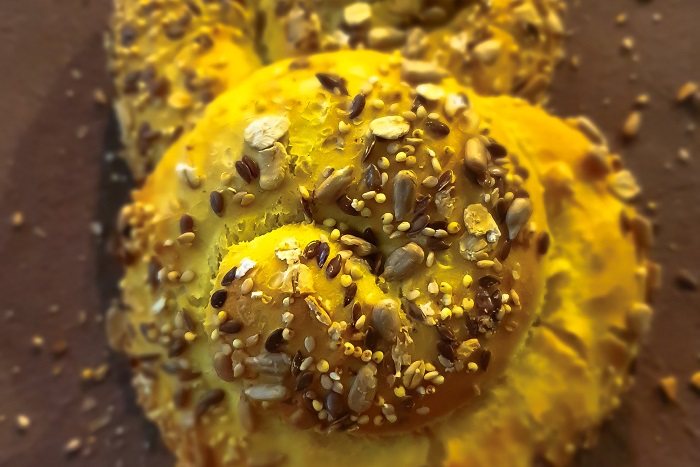

3. Pumpkin Challah or Sephardi Pan de Calabaza (pareve/no dairy)

Pumpkin is a popular ingredient in Sephardi dishes, according to food writer Emily Paster. Leah Koenig, author of "The Jewish Cookbook," argues that Jews helped normalize foods like pumpkin when they were new to European menus. In the "Encyclopedia of Jewish Food," Gil Marks notes that in Italy, pumpkin came to be associated with Jews. Pumpkin made early appearances in Mediterranean foods via Sephardi Jews in Syria, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Libya, Morocco, India, and Bukhara. Award-winning chef and cookbook author Joyce Goldstein suggests that the Sephardi community may have embraced pumpkin because the texture resembled meat and could be used for dairy and meat meals.

Pumpkin had seasonal appeal, especially during the High Holidays. As Gilda Angel, an expert in Sephardi foods notes, “Food made with pumpkin is served to express the hope that as this vegetable has been protected by a thick covering, God will protect us and gird us with strength.” One Hebrew word for pumpkin or squash, "qara," provides the pun for “tear or rip” -- any evil decree of the new year should be torn up. The word also sounds like the Hebrew for “called out.” That is, good deeds should be called out and recognized. Since a pumpkin contains many seeds, it also came to symbolize fruitfulness and fertility.

This Sukkot, reclaim these diverse autumn-infused baked goods from legendary and resilient Jewish communities around the globe.

Related Posts

Nourishing the Soul and Body with Bread

Tips to Fill Your Cup: 36 Ideas for a Rejuvenating Shabbat