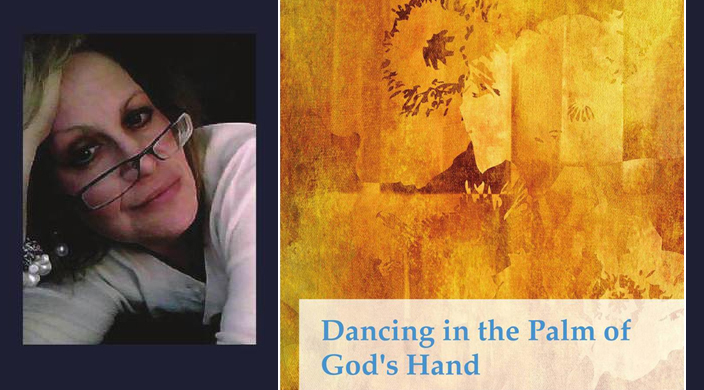

The essays and poems in Stacey Zisook Robinson’s Dancing in the Palm of God’s Hand (Hadassa Word Press) reveal a writer grounded in self-awareness, drawing readers in toward a comfortable intimacy.

In one moving essay, Robinson captures a poignant moment that many can relate to, as she describes the raw emotion of chanting Torah with her then-13-year-old son. In the poem “Twenty Three,” saying goodbye at a burial, Robinson captures another universal emotion – the wistfulness of loss.

This volume delicately cuts to the heart of what Robinson has dissected and pieced back together. Her words gracefully display private thoughts and places in which she has found escape from despair:

And then one day, after my long, self-imposed exile, I walked into a synagogue...I found something, through my voice - through music and song - that I didn't know was possible. I found a connection to God that was startling in its simplicity. It was prayer and forgiveness all at once.

We sat down with Robinson to discuss her new book, her writing process, and, of course, her Judaism.

ReformJudaism.org: When did you discover that you were a writer and what role has it played in your life?

Robinson: I love words. I love the shape of them and the magic of them. I love their power. I’m transfixed by stories and have always wanted to be able to do what fine writers can: transport and change and hold a reader with words. When I was newly sober, I used to say, over and over, “I want to be a writer!” A friend finally grumbled, “Stacey. A writer writes!” Oh, that. Still, I didn’t write for many years. I kept putting it off – I wasn’t good enough, old enough, funny enough, real enough to be a writer. I’m still surprised when I read something I’ve written and think, “Hey, that’s kinda good. That could’ve been written by a real writer!”

Many Jewish parents will be able to identify with the essay in which your son asks you to chant with him to help him prepare to become a bar mitzvah. You capture a moment and make it timeless and quite moving. Did you realize it was something you’d write about as you were living it?

There are times I am seized with an idea, or a sentence comes, completely unbidden, and my only response is to write, then and there. Someone once said to me, “I wish I was in your head as you were writing!“ My response was that all you would hear and see would be a great whoosh of air, travelling through nothing. I am absolutely sure that my subconscious is busy all the time, storing images and words, so that when the essay or poem is ready, it’s all there, capturing whatever moment in time moved me.

A recurring theme in your essays is your struggle with drinking. When and why did you first start writing about this revealing part of yourself?

It seemed natural to me to write something – in tribute, in remembrance, in gratitude. I write about the challenges I have with sobriety, even several decades into it, in part because I do still struggle. I write about struggling not just with sobriety, but with faith and doubt and God and parenting and working and everything in between. Writing is my way to figure stuff out, to stay sane, to quiet the voices in my head.

Most of your poems can be read as prayers. Is writing them a spiritual experience for you?

One of the most spiritual experiences I’ve ever had was writing “Twenty Three,” my interpretation of the 23rd Psalm. A friend’s son was dying, and it was a painful time. I could have sworn, when I was writing that poem, that I was consciously leaving God out of it; I was so angry with the idea of praising God in the midst of such pain. It wasn’t until later that I realized that God sang from every letter, every word, even with all of that anger.

Many of your poems and essays deal with your faith in God. Tell us about that search and how it led you to discover the power of Jewish communal prayer. What draws you to your congregation?

The jury is still out on the “faith in God” topic. That is an eternal dance, a wrestling match – sometimes a shouting match. It is my constant conversation with God – sometimes a whisper, sometimes a shout of anger or pain. It was less my faith and more my singing that led me to the concept of, and comfort with, communal Jewish prayer. I used to tell my students, “I came to services so I could sing. In time, I came to services so I could pray; singing is a bonus.” I sing and pray with others in the same way I study with others: To pray or study on my own, all I would hear is the sound of my own voice.

Stacey’s newest project is a poet-in-residence program. Learn more on her blog and website.