When the Germans launched their blitzkrieg conquest of France in 1940, they seized only 45 percent of the country. Much of the southern part remained “unoccupied.” To rule that region, the Nazis installed a subservient pro-German puppet regime, led by the aged, authoritarian World War I military hero, Marshall Phillipe Petain. It was headquartered in the spa resort city of Vichy.

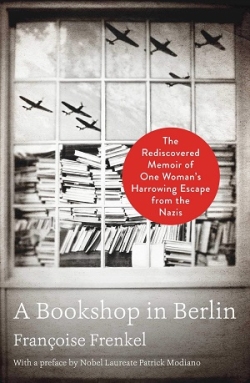

Perhaps as a result of Claude Rains’ portrayal of the corrupt, but benign Vichy French police chief in the 1942 film “Casablanca,” a myth emerged that Jews were somehow physically protected under the Vichy regime. Not so. Francoise Frenkel’s tightly written, highly personal A Bookshop in Berlin: The Rediscovered Memoir of One Woman's Harrowing Escape from the Nazis debunks this myth.

Born near Lodz, Poland in 1889, Frenkel as a young Jewish woman studied music in Germany and art in Paris. But French literature was her first love, and in 1921, only three years after the end of World War I, Frenkel and her Russian Jewish husband, Simon Reichenstein, opened a Francophile bookshop in the capital of Germany, France’s longtime, bitter adversary.

It was a gamble that paid off when the shop attracted a “curiously mixed” group of customers that included “eccentrics, artists, celebrities and well heeled women.” French literary giants Andre Gide and Andre Maurois lectured in her store during the Weimar Republic years that tragically ended in 1933, when Hitler gained power in Germany.

Despite official Nazi antisemitic policy, Frenkel’s store remained open even after the 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom. However, in August 1939 – less than a month before the start of World War II – Frenkel finally shuttered her bookstore and fled Berlin for what she believed was the physical and emotional security of her beloved Paris.

It would not be the last time she was forced to flee for her life because she was a Jew.

Frenkel became a refugee again when the Germans occupied the French capital, and she made a hazardous escape to the French Riviera city of Nice. There she joined other refugees in living a tense, worrisome life for two years under the increasingly anti-Jewish policies and actions of the Vichy authorities.

On August 26, 1942, Petain’s police and security gendarmes began rounding up Jews in Nice for deportation to concentration camps in France. To escape capture, a bewildered and terrified Frenkel used what little money she had left to bribe her way from one “safe house” to another. A Bookstore in Berlin describes the terror, despair and fear she faced as a 53-year-old woman on the run, constantly in fear of betrayal as the dreaded Vichy authorities closed in on her.

It was her good fortune to gain the protection of Monsieur and Madame Marius, a married couple who owned a hairdressing salon in Nice. She writes, “They spared no effort in their care and consideration of me.”

Frenkel was ever fearful that she would be turned over for a bounty to the gendarmes, who announced publicly: “We’re hunting humans now.” Especially high on the hunted list were Jewish children.

Frenkel describes one frightening scene in which, “…Mothers cut their wrists, others threw themselves under the [police] buses just as they pulled away with their tragic cargo…”

Desperate to escape to neutral Switzerland, in December 1942 Frenkel is betrayed at the border by her French “guide,” who turned out to be a treacherous smuggler who was paid by the Vichy regime for her capture and arrest.

Thanks to her hairdresser protectors and a still viable legal system, Frenkel was released. Finally, in June 1943 she managed to jump the barbed wire border to the safety of Switzerland.

Frenkel recounted her dangerous odyssey in a book published in 1945 with the title, Rien ou poser sa tete (No Place to Lay One’s Head). The book was subsequently lost to the world until 2010, when it was discovered in an attic in southern France. Five years later Frenkel’s book was republished in France followed by Smee’s recent excellent English translation.

Frenkel’s husband, who is never mentioned in the book, was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942, and most of her family living in Poland, including her mother, also was killed during the Holocaust.

There is a wonderful Hebrew expression that best describes Francoise Frenkel’s life after the war: Af al pi chen (Nevertheless to the contrary and despite everything). She returned to Nice, where she lived a quiet, unnoticed life until her death in 1975 at age 86.

I can imagine her spending the last 30 years of her life surrounded by leather-bound volumes of works in French by Gide, Maurois, Blaise Pascal, Francois de La Rochenfoucauld, Nicolas Chamfort and Paul Verlaine – just a few of Francoise Frenkel’s literary loves.

Francoise Frenkel’s remarkable memoir provides an eyewitness account of a frequently neglected aspect of the Holocaust: Vichy France and the Jews.

Rabbi A. James Rudin is the former head of the American Jewish Committee’s Department of Interreligious Affairs and author of seven books, most recently, Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Stephen S. Wise. He served as a U.S. Air Force chaplain in Japan and Korea