Manoel Dias Soeiro was born in Lisbon in 1604 into an outwardly Roman Catholic family that had been forced by the Inquisition to abandon its Jewish faith and practices.

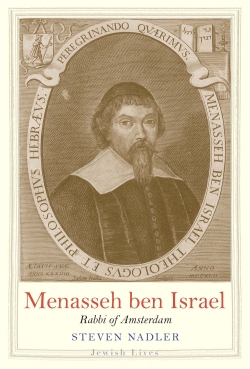

A half century later at the time of his death in Holland, Soeiro was the world’s most famous Jewish personality of his time, widely known to Jews and Christians as Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel.

In his excellent new book, Menasseh ben Israel: Rabbi of Amsterdam (Yale University Press), Professor Steven Nadler of the University of Wisconsin-Madison describes this remarkable transition.

Desperate to escape Portugal (the Inquisition authorities physically tortured Manoel’s father), the family escaped to Amsterdam in 1610, where refugees could reclaim their Jewish names and identities.

Nadler describes the complex political and religious balancing act required for a minority to survive in Amsterdam at that time. While many Sephardic Jewish refugees still had families living perilous lives as Catholics in Portugal and Spain, the Dutch themselves were engaged in the “Eighty Years War” (1568-1648) with their former Spanish political overlords. Yet, Amsterdam, because of its mildly tolerant political and economic climate, emerged as a major center of Jewish life.

At age 18, the intellectually gifted Menasseh, became the rabbi of an Amsterdam synagogue. He knew Portuguese, Spanish, Hebrew, Dutch, and had a working knowledge of Latin. Late in life, he learned enough English to communicate directly with Oliver Cromwell, Britain’s Lord Protector, in order to appeal for the readmission of Jews to England, reversing the royal expulsion order of 1290.

He wrote many books in various languages, including a work that addressed the problems of apparent inconsistencies in the Hebrew Bible. Menasseh drew upon myriad sources in his writings, including those of Moses Maimonides, the Greek philosophers, and Christian scholars. In addition to rabbinical duties, Menasseh established and operated the first Hebrew language printing press in Holland, and his books were distributed throughout Europe.

One of his greatest challenges was arbitrating among colleagues and the community’s lay leaders who lived in constant fear that any move seen by the Dutch Reformed Church as a threat to its hegemony could result in their expulsion from Holland. To complicate matters, the Church was plagued with internal strife and theological divisions.

Amidst the divisions and chaos of early 17th century Amsterdam, Menasseh sensed a unique opportunity. He engaged Christian clergy, theologians, and philosophers in vigorous intellectual and interreligious dialogues. While the fearful Amsterdam Jewish “Establishment” strongly disapproved of such efforts, their security and well being were ultimately enhanced as a result of their rabbi’s many Christian contacts.

On a personal note, as a rabbi who spent much of my professional career building positive relations between Christians and Jews, I regard Menasseh as a visionary predecessor. He faced several of the same issues I did, such as supporting Christians who sought knowledge about Jews and Judaism for their own enlightenment and spiritual growth, while opposing those who used this knowledge to bolster their campaign to convert Jews to Christianity.

Menasseh’s last years were filled with personal tragedy and disappointments. He outlived his two sons, and he did not succeed in his decades-long campaign for the readmission of Jews to England during his lifetime; the edict rescinding the 1290 expulsion decree came seven years after Menasseh’s death in 1657.

This well documented book casts doubt on the belief that Rembrandt and Menasseh were neighbors or close friends in Amsterdam. Nadler writes: “It is certainly possible, …but really we have no idea.” Nor did the famous artist create a portrait of the rabbi.

Menasseh was not among the Amsterdam rabbis who excommunicated Baruch (Benedict) Spinoza in 1656. Menasseh was in London that year dealing with Cromwell, and the rabbi’s controversial work with Christians placed him outside the established rabbinic group that viewed Spinoza’s views as heretical.

Nadler’s research provides the political and religious background for the 1654 arrival in New Amsterdam (now New York City) of 23 Sephardic Jews who fled Recife following the Portuguese capture of that area of Brazil from the Dutch. To escape the Inquisition, which was not far behind, the refugees sailed to New Amsterdam, where the colony’s anti-Jewish governor, Peter Stuyvesant, sought to deny them admission. Going over his head, they appealed to the directors of the Dutch West India Company, which included Jews. Stuyvesant was overruled, and the immigrants remained in New Amsterdam, albeit with certain restrictions.

The significant interreligious work done by Menasseh ben Israel along with the growing influence of the Amsterdam Jewish community arguably contributed to this early victory for American Jewry. We owe him a great debt of gratitude.

Rabbi A. James Rudin is the former head of the American Jewish Committee’s Department of Interreligious Affairs and author of seven books, most recently, Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Stephen S. Wise.

View all posts by Rabbi A. James Rudin