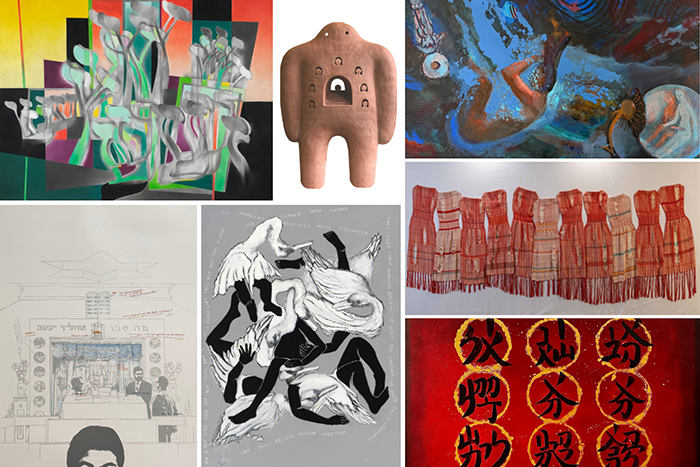

The Heller Museum at Hebrew Union College in New York is proud to present “Children of Ruth: Artists Choosing Judaism,” an unprecedented international group exhibition by artists who have found a spiritual home in Judaism through conversion. Their journeys evoke the message of the Book of Ruth, one of the five megillot (scrolls) of the Bible, which tells the story of a convert to Judaism who became an ancestor of King David.

Curators Nancy Mantell and Susan H. Picker focus on 17 artists’ diverse paths to Judaism and their individual journeys. Artists hailing from New Zealand, Japan, Hong Kong, Norway, the Netherlands, Canada, and the United States employ a variety of media to portray their experiences.

Tetsuya Noda from Japan uses complex woodblock, silkscreen, and photographic techniques to create prints in his Diary collection, which now contains over 500 pieces. “Diary: June 11, 1971: Bet Din for Conversion” depicts the artist standing before a Jewish rabbinical court of three presiding rabbis, along with many annotated symbols of Judaism. The ceremony was shortly followed by Noda’s marriage to Dorit Bartur, the daughter of Moshe Bartur, the Israeli ambassador to Japan at the time.

Yona Verwer’s Immersion series began when she converted to Judaism in the 1990s. Going to the mikvah is the final part of the conversion experience, marking the transition to becoming a Jew. Verwer explains that “Immersion VIII” portrays her “mikvah experience: the joy of weightlessness, the reference to the marriage ritual (before which one also goes to the mikvah), and the feeling of being spiritually elevated.” Verwer is from the Netherlands and includes her interpretations of Dutch artist Hieronymous Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights.”

Carolyn Carson’s family had been ministers for generations, but the artist found her spiritual home in Judaism. “As a resident of Pittsburgh,” she says, “the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre tore at my heart.” She explained that her work, “Daughters of Ruth,” depicts the scars of worldwide antisemitism and her feeling of belonging as a Jew among the Jewish people.

Artist Mary Apikos states, “In some ways, conversion to Judaism is simply like having a key that was always there in my life. It is like returning home.” Her work, “We Can Only Be Human Together,” is a commentary on the harm inflicted on children when adults wage war. The mixed media drawing depicts the Brothers Grimm story of “The Six Swans,” in which enchanted brothers can blow away their feathers and become human for 15 minutes a day if they work together.

Although Kate Hendrickson had a trusted circle of friends and family who supported her exploration and eventual conversion to Judaism, she explained that there were others in her life who were not as supportive. “I could not share this personal journey due to a sense of inevitable disapproval,” she recalled. That internal upheaval led to a series of drawings, Concealed Faith, in which she selected Hebrew words that were meaningful to her, but disguised, leaving only tiny traces appearing here and there. As she became more comfortable revealing her Jewish identity to a broader circle, she began a new series: Revealed Faith, where the Hebrew letters and words became more discernible, as seen in “Tree (EHTS).”

Hong Kong-born Carol Man accesses her Chinese and Jewish identity to create a Chinese-Hebrew calligraphy following the tradition of both languages, in which the text goes from top to bottom in Chinese and right to left as a nod to Hebrew. In “Pirkei Avot 1:10,” she depicts a teaching that states, “Love work, hate acting superior, and do not attempt to draw near to the ruling authority.” This credo, which shares principles from both cultures, was proudly displayed by Man’s son on his dormitory door when he attended university.

Annaliese Rosa turns to the golem, the Jewish legendary creature brought to life through magic, as a mystical protector of the Jewish community. Her “Temple Golem” ceramic sculpture is emblematic of her life as a Jewish person in New Zealand. She explained:

“Golems are creatures on the fringes, accidental queer icons, and safe, sacred spaces. The golem guards the temple within myself, where my Judaism gives fire to my activism and pride. The golem stands up for the Jewish values I was taught during my conversion and after it. The golem reinforces the sacred teachings of community, tradition, and .”

These artists are vital contributors to Jewish culture and esteemed members of the Jewish people, as Deuteronomy 19:9-14 explains:

“You stand this day, all of you, before the Eternal your God...to enter into the covenant of the Eternal your God…I make this covenant…not with you alone, but both with those who are standing here with us this day before the Eternal our God and with those who are not with us here this day.”

View the exhibition catalog to see more artists’ works in “Children of Ruth.”

Related Posts

Poems of Sorrow and Hope

Where Have All the Jewish Movies Gone?