While my daughter, Mimi, was walking in a Brooklyn mall recently, pushing her baby in the stroller, she was approached by a modestly dressed girl of about 12 years old. Speaking with a slight accent, the girl asked, “Are you Jewish?”

When Mimi answered yes, the girl called out excitedly, “She’s Jewish, she’s Jewish!” Suddenly Mimi was surrounded by seven or eight Lubavitcher ’tween girls who offered her a pair of Shabbat candlesticks.

“I already have candlesticks,” my daughter said, so the girls instead handed her some money to put in their tzedakah (charity) box, saying, “It’s a mitzvah (commandment).”

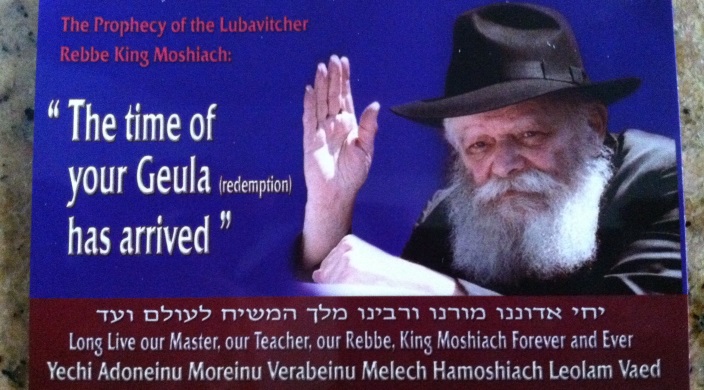

“It’s a bigger mitzvah to put in my own money,” Mimi responded, inserting some coins. As my daughter was leaving, one of the girls placed a picture of the last Lubavitcher rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, in her son’s little hand.

“It will bring him joy and peace,” they assured her.

When these girls grow up, its likely that some will marry rabbis, and the newlyweds will be recruited and dispatched as emissaries to just about every place on earth where Jews can be found.

No town is too small for the establishment of a Lubavitcher-Chabad center. I was not surprised when the Lubavitchers opened a center in my town of Ridgefield, CT, which has only 200-250 Jewish families and already served by a Reform synagogue. The young Lubavitcher rabbi and his wife offer Jewish families in our town worship services, classes, and summer camps at no charge, relying on tzedakah contributions both to fund the growing family’s livelihood and the center’s operational costs.

What’s behind this drive to connect with Jews - and only Jews - from Ridgefield to Riga and to more than 1000 other locations across the planet?

The answer lies in the writings of Shneur Zalman (1745-1812), the progenitor of this Hasidic sect, which derives its name form the early center of its activities in the Belorussian village of Lubavitch. Zalman was the only founding figure of Hasidism who wrote a systematic account of his religious teachings. Commonly known as the Tanya and studied to this day by Lubavitcher Hasidim, its climactic doctrine is the prophetic teaching that the coming of the Messiah is drawing near, and that every Jew, from the most unschooled and alienated to the most learned and pious, has a role to play in the redemption of the world.

Shneur Zalman borrowed from the mystical writings of the16th-century kabbalist, Isaac Luria, who taught that Jews need not wait patiently for the Messiah, but can instead hasten his advent through the ritual observance of mitzvot. New in the Tanya is the democratization of Lurianic Kabbalah by giving every Jew a vital role to play in the messianic drama by engaging in tikkun olam (healing or perfection of the world).

As the 37th chapter of the Tanya states:

Now this ultimate perfection of the messianic era…is dependent on our actions and [divine] service throughout the period of exile….the general vitality of this world will also emerge from its impurity and sickness and will ascend to holiness, to become a chariot for God….”

It is noteworthy that the messianic idea imbedded in Reform Judaism is also heavily influenced by the Lurianic Kabbalah idea of tikkun olam. We agree with the Lubavitcher Hasidim that every Jew has a role to play in perfecting the world.

Reform Judaism, however, differs from the Lubavitcher messianic idea in three essential ways. First, we emphasize engaging in social justice rather than in ritual observance. Second, we do not envision the coming of an individual Messiah, but of a messianic era. Third, we have no deadline for bringing about the “Sabbath of the World.”

For the Lubavitchers, in contrast, the timing of the Messiah’s arrival is a matter of utmost significance.

Shneur Zalman, who lived in the sixth millennium, according to the Jewish calendar, predicted the Moshiach (Messiah in Yiddish) would come in the seventh millennium. Menachem Mendel Schneerson became the Lubavitcher rebbe in 1951, just as the seventh millennium was approaching. Feeling a sense of great urgency, the Brooklyn-based rebbe dispatched his disciples on a world-wide campaign to “bring the Moshiach now.”

Many Lubavitcher Hasidim regard Rebbe Schneerson, who died in 1994 with no successor, as the very incarnation of the Messiah. His visage adorns the homes of his disciples, and exuberant ‘tween girls sometimes place images of the “King Rebbe Moshiach” in the hands of Jewish babies to bring them “joy and peace.”

This piece includes excerpts from JEWS: The Essence and Character of a People by Arthur Hertzberg and Aron Hirt-Manheimer.

Related Posts

From Scared to Sacred: Healing Our Collective Trauma in the New Year

Two Years Later: Memory and Meaning on October 7th