It would be rare today to visit a synagogue and not see a visual portrayal of the two rounded tablets of the law. You might even say that the Ten Commandments have become the visual shorthand for Judaism.

This is a relatively new phenomenon. Among earlier generations of American Jews the public display of the Ten Commandments was controversial, so much so that it split the membership of New York’s Congregation Anshi Chesed, a traditional synagogue soon to cast its lot with Reform Judaism.

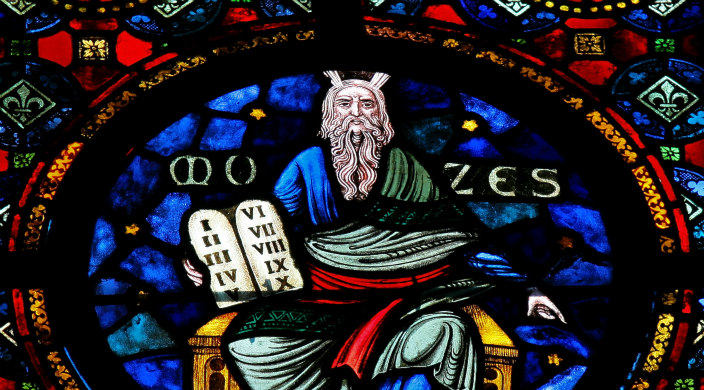

In May 1850, at a dignified ceremony attended by Mayor Caleb S. Woodhull, the members of Anshi Chesed proudly dedicated their new building, located on Norfolk Street between Stanton and Houston in what was then New York’s kleine Deutschland (Little Germany). Designed by the esteemed Berlin architect Alexander Saeltzer, the sanctuary displayed a circular stained-glass window of the Ten Commandments.

“These stained-glass windows have a very pleasing effect,” said an article in the New York Daily Tribune. “The Commandments, instead of being on two tablets, are each on a separate pane of glass, around the window, surmounting the Ark,” The local Jewish press also praised the window, but some particularly vocal congregants questioned this innovation.

Eager to resolve this “weighty problem,” the synagogue’s lay leaders formed a committee to seek rabbinic advice on whether the commandments should “remain as they are painted in a circle on stained glass” or “if it is against the din (Jewish law) and ought to be fixed in the usual way on two tablets.”

But what exactly did they mean by the “usual way”? Were they troubled by the Decalogue being rendered in glass? Or did something else cause their upset?

Since the emancipation of the Jews in the late 19th and early 20th century, stained glass windows were incorporated into many newly built, grand, European synagogues in a self-conscious act of cultural appropriation and affirmation. Congregation Anshi Chesed was no exception.

Perhaps it was not the medium, then, but the way in which the Decalogue was pictured that disturbed some congregants – pane by pane, commandment by commandment, encased in a circle like the spokes of a wheel – a striking departure from the typical symmetrical image of rounded, twin tablets. Or the issue may have been the window’s prominence, situated front and center, appearing to eclipse even the Ark itself.

Eventually, the congregation received an answer to its inquiry: “There [is] nothing in the laws [rabbinic law] which prescribes any particular form; consequently that it is not against the din to have them fixed as they are at present.” All the same, the response did acknowledge that Anshi Chesed’s Ten Commandments were, “as a general thing, fixed differently.” And there the matter rested.

But not for long. About a year later, some synagogue members agitated once again for its removal, the committee was reinstated, and a traditional twin-topped Ten Commandments was constructed in Italian marble and placed atop the Ark. To satisfy those congregants who liked the circular commandments, the original window remained in place until well into the 1970s, when vandals made off with it.

Ironically, though the proponents of the round-topped, twin tablets thought of it as a Jewish concept, this configuration of the Ten Commandments was actually a “medieval Christian invention that gradually spread through western Christendom,” explains the renowned art historian Ruth Mellinkoff. By the 19th century, the twin-topped version became the norm in America, too.

The Jews had a very different historical relationship to the Decalogue. Though it was highly valued, other elements in Jewish culture such as the menorah, were far more widely publicized in visual form. And even when depictions of the Decalogue did adorn an Ark or a Torah mantle, they did not function on their own as autonomous images but were bound to a ritual object.

The Ten Commandments’ bold, ornamental stained glass window at Congregation Anshi Chesed stood all that on its head.

At the time of the synagogue’s dedication, social and cultural exchanges between Christians and Jews had become more frequent, and the prospect of finding common ground was increasingly touted as a social good, a benefit to the Jews as well as their Christian neighbors. How better to usher in a new order of comity than by harnessing the symbolic – and shared – power of the Ten Commandments?

The congregants of the Norfolk Street synagogue faced a choice: to embrace distinctiveness or a shared idiom. In the end, they sought to accommodate both.

We want to see your synagogue's Ten Commandments artwork! Post your photo on our Facebook page or tweet it at us on Twitter.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies and History at George Washington University, is the author of Set in Stone: America’s Embrace of the Ten Commandments (Oxford University Press, May 2017).