Aaron Hahn Tapper’s new book, Judaisms: A Twenty-First-Century Introduction to Jews and Jewish Identities, takes a unique approach in exploring the multifaceted and intensely complicated characteristics of this age-old, ever-changing community, weaving together the multiple ways Jews identify in terms of culture, ethnicity, nation, nationality, race, religion, and more through the lenses of historiography, political identities, and social psychology.

We chatted with Hahn Tapper, the Mae and Benjamin Swig Professor in Jewish Studies and the founding director of the Swig Program in Jewish Studies and Social Justice at the University of San Francisco, about his book and the detailed, nuanced topic it addresses.

ReformJudaism.org: There are a multitude of books on Jews and Judaism. What prompted you to add yet another?

Aaron Hahn Tapper: When I started teaching an introduction to Judaism class at the University of San Francisco in 2007, I wanted a core book to use that really resonated with my students, who come from incredibly diverse backgrounds, most of them not Jewish. To have a meaningful conversation with my students, I needed a book that used social identity as an entry point, rather than a set of religious beliefs and practices. I was unable to find the right fit. So, I wrote my own text.

What made you decide to include your own narrative as an American Jew in the book?

My own story illustrates the complexity, diversity, and fluidity of Jewish identity I myself have experienced as an American Jew.

I attended 13 years at Jewish day schools (7 at Solomon Schechter and 6 at Akiba Hebrew Academy, both located outside Philadelphia), spent 10 summers at Camp Ramah in the Poconos, studied in Orthodox yeshivot [religious seminaries] in Jerusalem – but then I took a relatively divergent path from other Jews I grew up with.

I backpacked in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, studied Arabic in Fez, Morocco, Cairo, Egypt, and even in Bir Zeit, in the occupied West Bank. Along the way, I completed a master’s degree in theological studies from Harvard and a PhD in religious studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Did you have any eye-opening Jewish experiences while studying abroad that impacted your understanding of the politics of Jewish identity?

Probably my biggest “aha” moment of my twenties was the summer I spent in Morocco. I was able to travel all over the country and sought out Jewish spaces. One weekend, when attending synagogue in the Old City of Marakesh, I finally got what it meant to identify as a Jewish Arab, or Arab Jew: the clothing, the customs, the pronunciation of Hebrew. It was profound.

Over the next decade, I came to realize how marginalization works within the Jewish communities and how Ashkenazi-centric my upbringing was.

Here’s another: I was studying at an Orthodox yeshiva in the summer of 1994 when I was called into the school office and told by a rabbi that I might not be Jewish because my mother converted to Judaism under the auspices of the Conservative Jewish movement.

Eventually, I learned that, from a halachic [Jewish law] standpoint, my mom’s conversion was kosher, but the incident raised a number of questions for me. Can someone’s identities be deleted overnight on a technicality? Does Jewishness depend solely on ritual and legal requirements, or are Jewish identities more malleable than that?

What are some of the different ways Jewish identities are defined today – and who is to judge whether they are legitimate?

There is no overriding authority in Judaism with the final say as to who belongs to the Jewish people and who does not. Different factions have determined their own definitions, and these have changed over time.

Those who define a Jew halachically say you’re Jewish if birthed by a Jewish mother or converted to Judaism by a rabbi or beit din [rabbinic court] they deem legitimate. Some people follow patrilineal descent, others matrilineal. Some people say you’re Jewish if you define yourself as such. And then there’s the definition of a Jew according to the State of Israel.

To make matters more complicated, identity is not simply a matter of self-identification of an individual or even of a community.

In the case of marginalized communities, more often than not, it’s those outside a community who make definitional decisions. Whether it’s African-Americans in U.S. history or Jews under the Nazi regime, dominant groups have commonly had the final say in what’s what regarding subordinated groups.

In 2017, many (if not most) Jews in the world have the luxury of choosing to be Jewish and in what manner. Sociologists call this “social identity performance”; it depends on the behaviors and choices people present to each other and to the outside world.

Are you hopeful about the future of Jews and Judaism(s)?

Yes. I think the cultural adaptability of Jews, or what artist Frederic Brenner calls a “portable identity,” is one of the primary reasons Jews have survived and thrived – and, I believe, will continue to do so.

But, more importantly, I return to the question posed by the renowned twentieth-century rabbi, Marshall Meyer. When asked this same question, he said, “There has been a deep concern with Jewish continuity and with the survival of the Jewish people. Let us begin by asking, survival as what?”

Related Posts

10 Jewish Athletes You Need to Know About

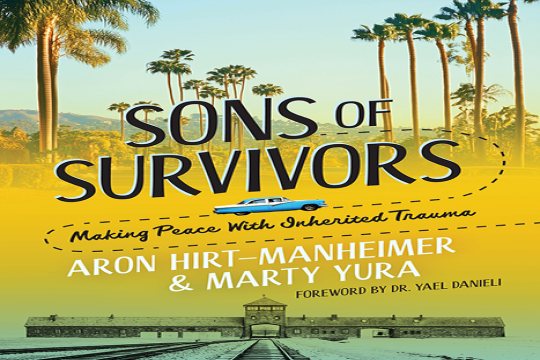

Sons of Survivors: Aron Hirt-Manheimer on Memory, Trauma, and Love