Marsha Bryan Edelman, Ed.D., author of Discovering Jewish Music (Jewish Publication Society), is a professor of music and education at Gratz College in Melrose Park, PA. A graduate of Columbia University and the Jewish Theological Seminary, she holds degrees in general music, music education, Jewish music, and Jewish studies; she is also active as a choral singer and conductor, and has worked with the Zamir Choral Foundation in various musical and administrative capacities for more than 35 years.

We interviewed Edelman about the Kol Nidrei melody associated with the High Holidays.

ReformJudaism.org: What is the origin of the Kol Nidrei melody?

Marsha Bryan Edelman, Ed.D.: The melody that stirs the heart of Ashkenazic Jews is of unknown origin, but is part of a body of music known as "MiSinai melodies" that emerged in Germany between the 11th and 15th centuries. "MiSinai" literally means "from Sinai." Of course, we know that none of these tunes came from anywhere in the Middle East, but the hold they have had on Ashkenazic Jews has made them as venerated as if they "came down from the mountain."

How would you describe the melody, musically?

It combines syllabic chanting, one note per syllable, with melismatic passages, in which one syllable may be extended over several notes. Many of the musical phrases used in Kol Nidrei are related to (or at least reminiscent of) other themes that are used throughout the High Holiday period. Observers say that the MiSinai melodies are "majestic" and "lofty" and are therefore appropriate to the liturgical themes of the day.

In fact, the extensive use of melisma throughout the High Holidays makes the period and its music quite distinctive. Given the importance of Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur, and the emotional "baggage" that most people carry as we contemplate "who shall live and who shall die," this music adds a degree of theological weight to the service.

When the Reformers of the 19th century abandoned the rest of traditional Ashkenazic nusach (the traditional melodies and motives for chanting the liturgy) as being too old fashioned and unsuited to congregational and choral singing, they still preserved the MiSinai melodies, most of which are associated with the High Holy Days.

Can you explain the marriage of this particular text and tune?

The text of Kol Nidrei – the nullification of personal promises that cannot be fulfilled – has none of the beautiful poetry that characterizes so much of our liturgy (and it was not included in Reform prayer books until the 1978 publication of Gates of Repentance). So the question of why we have such a lofty melody for such a pedestrian text is a good one.

The reason lies less in the actual text than in the significance of the moment. Since the beginning of Rosh HaShanah, we have been engaged in a period of self-reflection known as the "Ten Days of Repentance" (Aseret Y'mey Teshuvah). On Yom Kippur, we have reached the last lap in our spiritual marathon: It's now or never.

There is a certain electricity in the air as the synagogue fills – usually to its full capacity. The recitation of Kol Nidrei actually comes before Yom Kippur begins (since one is forbidden from negotiating business on a festival), but the custom is to repeat the chanting of Kol Nidrei three times – both to fill the time until the sun sets, and to be sure that any latecomers to the service can hear it at least once.

Obviously, the recitation of anything three times has a built-in capacity for boredom, so various customs have emerged to enhance the chanting. Typically the cantor will sing it softly the first time, and sing progressively louder with each repetition. It is also customary to raise the key with each repetition. As the music gets progressively louder and higher, there is an increased charge in the synagogue atmosphere.

With all of this emotional drama playing out, it is not surprising that, over time, a fairly elaborate musical composition has emerged.

Does the chanting of Kol Nidrei vary within the Ashkenazic community?

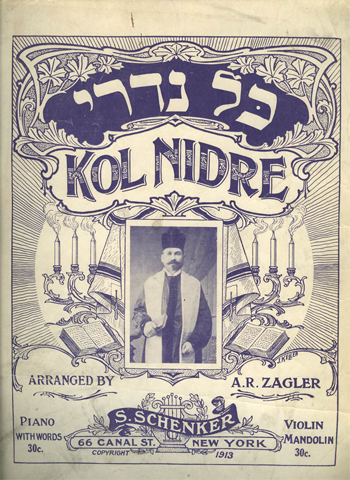

To be sure, there are variations in the way different cantors chant the tune. As with any "folk" melody transmitted over time, each "performer" evolves his or her own style. By the time versions of the Kol Nidrei melody began to be notated (in the late 18th century), there were significant differences in the texting (which syllables correspond to which notes) and in the placement and particular pattern of each individual melisma.

But notwithstanding these variations, there is a clear consensus over the broad outlines of the tune, as well as quite a number of details, especially the distinctive intervals that mark its haunting opening.

How do Ashkenazic and Sephardic versions differ?

Considering the fact that over the past millennium Ashkenazic Jews have lived on several continents and among quite different majority cultural influences, there is a surprising degree of uniformity in the tune used in Ashkenazic congregations.

On the other hand, Sephardic versions of Kol Nidrei vary both in melody and performance practice from one community to the next. Sephardic variations range from fairly simple chants from the Babylonian (Iraqi) tradition to a whispered chant with no melody at all in the Carpentras (Provencal) tradition of southern France to a fairly elaborate melody of the Spanish-Portuguese Jews which is stylistically reminiscent of the Ashkenazic tune but substantively different.

How have Reform synagogues shaped Kol Nidrei?

Modern congregations have found ways to adapt the chanting of Kol Nidrei to their evolving sensibilities about the role of music in the synagogue. Composers like Salomon Sulzer (Austria, 1804-1890) and Louis Lewandowski (Germany, 1821-1894) were among the first Jewish music professionals with organ accompaniment at their disposal.

At the same time, both of these men – and apparently their congregations as well – appreciated the role of nusach in general, and the MiSinai tunes in particular. Lewandowski's setting of Kol Nidrei for cantor, choir, and organ has become the standard in many congregations; composer Sholom Secunda's (1894-1974) setting (famously performed by opera singer Richard Tucker) is a somewhat more recent addition, still faithful to the original melody but with richer parts for the choir.

It is also interesting to note that contemporary congregations have become increasingly open to the use of a wide variety of accompaniments for the service in general, and Kol Nidrei in particular. Many congregations add winds and/or strings, and some include an adaptation of Max Bruch's (1838-1920) setting of Kol Nidrei (for cello and orchestra) for at least one repetition of the text.

Have women cantors influenced how Kol Nidrei is sung?

There is as much variety among women's voices as there is among men's, and obviously no one piece of music can possibly sound the same sung by everyone. But whether it is the emotional weight of the moment or the nearly infinite ways that Kol Nidrei has been performed, women have demonstrated that they can deliver artistically beautiful and spiritually meaningful renditions of this classic.

Does Kol Nidrei practice differ denominationally?

It is hard to make general statements about practices across the streams of Jewish practice because there is nearly as much variation within denominations as there is among them.

That said, Reform cantors tend to be more likely to add choirs and/or instrumental accompaniment to their renditions than Conservative cantors, but both are sometimes used in Conservative synagogues. In Reconstructionist synagogues especially, the emphasis on congregational participation and often the absence of a formally trained cantor leaves the musical performance limited to a lay solo singer.

Orthodox synagogues of the past were frequently at the core of the Golden Age of hazzanut that saw virtuoso cantors, such as Joseph "Yossele" Rosenblatt, Moshe Kusevitzsky, and Gershon Sirota, presiding over choral synagogues with large male choirs. Yom Kippur services became "events" that would draw such crowds that the police would be called in to control them! These days most Orthodox synagogues have an unaccompanied solo cantor on the for the recitation of Kol Nidrei.

There have been many stage performances too.

Yes, and often these compositions have nothing directly to do with the Jewish community.

The Bruch work of 1880 is the most famous example. Although Bruch learned the melody from his friend, Cantor Abraham Lichtenstein (whose colleague at the Oranienburgerstrasse Shul in Berlin was none other than Louis Lewandowski), Bruch never intended his concerto for ritual use. In fact, famed Jewish ethnomusicologist Abraham Zvi Idelsohn pronounced the Bruch concerto a brilliant masterpiece, but noted that the melody had entirely lost its Jewish character in its translation to the concert stage.

The main theme in the sixth movement of Beethoven's String Quartet Op. 131 also appears to be based on the Kol Nidrei melody. Beethoven was apparently approached by leaders of the Jewish community in Vienna to compose music for the inauguration of a new synagogue. Since they were looking for music of a "Jewish character," they supplied the composer with what they considered important examples of Jewish music, among them Kol Nidrei. The commission was never completed, but since this is the only formal connection that can be established between Beethoven and the Jewish community, this brief contact is the likely source of the composer's inspiration.

Has the melody crossed over into pop culture?

Al Jolson sang it in The Jazz Singer, the first "talking" movie. Neil Diamond sang it in the 1984 remake. The Kol Nidrei theme is now part of pop music as well. Perry Como recorded the Kol Nidrei (with Johnny Mathis doing "Eili, Eili, Lamah Azavtani" in his 1956 album I Believe).

In 1968 a rock band called the Electric Prunes produced a "composition" called "Release of an Oath" and subtitled "The Kol Nidrei: A Prayer of Antiquity," but its title track by David Axelrod featured an English adaptation of the text, and the music was only loosely based on the MiSinai tune. Perhaps the most unexpected performance of Kol Nidrei I've heard was recorded on an island in the Caribbean by a band playing sitar, tabla, oud, dumbek, and other instruments.

I admit to having conservative, almost parochial tastes when it comes to liturgical music. I can be stirred by new approaches to Jewish texts: some of Ernest Bloch's work in Avodat HaKodesh (Sacred Service) is breathtaking. But I suppose I'm a creature of habit and, yes, habituated to the notion of "if it ain't broke, don't fix it." The Kol Nidrei melody has been an integral part of Jewish tradition for hundreds of years, and will no doubt continue to be one of the most beloved melodies of our people.

Listen to recordings of the Kol Nidrei melody: