Book Review: ...And Often the First Jew

Rabbi Stephen Fuchs and his wife, Victoria, had a choice to make, a choice that would transform their lives. Should they cut all ties with Germany, where their parents were born and survived the Holocaust, or should they begin a positive dialogue with Germans?

They opted for the latter, devoting themselves to a simple yet profound message of reconciliation and hope: Wir können die Vergangenheit nicht ungeschehen machen, aber wir können gemeinsam an einer besseren Zukunft arbeiten. (We cannot undo the past, but the future is ours to shape.)

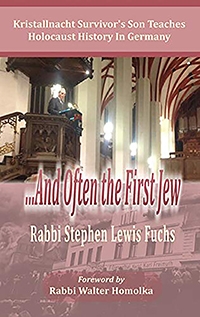

The couple’s bittersweet mission is laid bare in …And Often the First Jew (Mazo, Jerusalem), a 136-page collection of diary-like essays. The title represents the sad fact they are the first Jews many people living in postwar Germany had ever met.

Every time Victoria visits Germany, she can’t help wondering what German men and women “of a certain age” were doing while Jews were being persecuted and murdered by their countrymen during the years between 1933 and 1945.

Interestingly, although the husband and wife team returned to Leipzig (where Stephen’s father was arrested in November 1938 on Kristallnacht and later imprisoned in Dachau), and although Victoria’s mother, Stefanie Steinberg, was born in Breslau (now the Polish city of Wroclaw) and her father in Essen (home of the Krupp armaments factories), the Fuchs’ concentrated on medium-sized cities and towns that were “off the beaten path.”

Having established positive interreligious relationships with a host of Lutheran and Roman Catholic clergy and laypeople, the American couple has been able to examine aspects of the Holocaust with thousands of Germans, many of them born after the war, through sermons and educational programs. Rabbi Fuchs has spoken in more than 20 churches where no rabbi had ever spoken before.

Perhaps one of Rabbi Fuchs’ most poignant public sermons took place on October 26, 2014 in Kaltenkirchen, a picturesque village where 700 prisoners had died during the war in a nearby concentration camp and where the local pastor had shed his ecclesiastical robes for the uniform of an SS officer. (After the war, he was tried and convicted of war crimes for the murder of 2,000 to 3,000 Jews.)

After visiting the camp, Rabbi Fuchs preached in the local church. He recalls the experience:

During the church service people looked back and realized the horror of the era with genuine regret. There was visible emotion, [because] …most of those in the congregation had lived most of their lives [during the Holocaust]…[in addition]… some 80 students listened with rapt attention – some had tears in their eyes – as Vickie spoke about her mother and I spoke about my father. We emphasized how her mother and my father were among the truly lucky ones to escape the inferno before it engulfed Europe’s Jews. Still both Vickie’s mother and my father suffered, and it is important for students to understand their history…

Victoria’s artistic mother, who lives in San Francisco and still paints, emerges in the book as a true heroine. Underlying her daughter and son-in-law's teaching in German schools is a traveling exhibit about her terrifying personal experiences before she found safety in the United States.

Rabbi Fuchs, who is currently the rabbi of Congregation Bat Yam on Sanibel and Captiva Islands in Florida and is a past president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, tells us that his beloved father, Leo, had never spoken to him in detail about his horrific ordeal in Nazi Germany. He writes:

I am so thankful, my father, that you made it out of Kristallnacht – and out of Germany – alive…and I hope you are proud that I am standing here today (in a Leipzig church). But I cannot be sure.

I cannot be sure because you never, ever spoke to me of the night I have come to this place to commemorate.

You spared me the trauma that – as I now know – scarred you. But I thank you, for though you were scarred, you persevered…

To this land of those who perpetrated the greatest horror that I can imagine, I come to say: Remember!

And indeed, I shall remember.

Much has changed in Germany since Rabbi Fuchs first visited Leipzig in 1982. At that time, only 67 Jews lived in the city. Today, the number has expanded to about 1,300, and it is estimated that Germany’s Jewish population now numbers 130,000.

This extraordinary demographic growth rate increases the odds that, going forward, Stephen and Victoria Fuchs will not be “the first Jews” Germans meet.

Rabbi A. James Rudin is the former head of the American Jewish Committee’s Department of Interreligious Affairs and author of seven books, most recently, Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Stephen S. Wise. He served as a U.S. Air Force chaplain in Japan and Korea.