In 2006, the State of Israel proclaimed Martha and Waitsill Sharp “Righteous Among the Nations” – an honor bestowed by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum and memorial in Jerusalem, upon non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. The Sharps became two of only five Americans so recognized.

In presenting the designation, Mordecai Paldiel described the Sharps “an example of the minority among our righteous. The rescue operation was not thrust upon them. This is not a case where a person knocks on the door and says, ‘Help me! I just escaped from a ghetto, I need sanctuary. Can I stay in your home?’ In such a case, the rescuer becomes a rescuer on the spot…. the Sharps were motivated from the beginning to go into the kingdom of hell and try to get some people out. For this we honor them.”

In the wake of the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia in March, 1939, Rev. Waitsill Sharp of the Unitarian Church in Wellesley, MA, received a surprise call from the Rev. Everett Baker, vice president of the American Unitarian Association. He invited him and his wife, Martha, to travel to Czechoslovakia to help provide relief to people trying to escape Nazi persecution in “the first intervention against evil by the denomination to be started immediately overseas.” The mission would involve secretly helping Jews, refugees, and dissidents to escape Europe’s expanding Nazi threat. The Sharps would risk imprisonment, torture, even death. Seventeen other church members had declined. Though they had two young children at home, the Sharps accepted. They expected to be gone for several months. Instead, their mission would last almost two years.

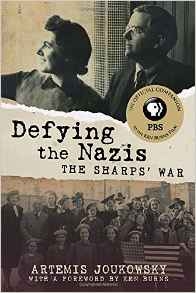

The Sharps never published their own memoirs and rarely spoke in public of their accomplishments. Their story would be told by their grandson, Artemis Joukowsky, author of Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War (Beacon Press, 2016), the companion to a Ken Burns PBS documentary (airing September 20, 2016).

As one reads Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War, one cannot help but conclude that the Sharps were a morally exemplary couple, though one can certainly question their decision to leave two young children behind. On the other hand, making that kind of personal sacrifice is what makes the Sharps’ so exceptional as heroes.

Their story reads like a spy novel, full of unexpected turns; yet it is also nuanced and complex.

The Sharps were not trained in espionage; they were two “ordinary” people—a minister and his wife, a father and a mother— who left the quiet, secure world of Wellesley, MA – a town in which few Jews lived at the time – for prewar Prague and later Vichy France. They learned the secrets of intelligence on the job, outwitting the Nazis at every turn by devising codes, avoiding surveillance, laundering money (Waitsill’s specialty). They smuggled several hundred people, people to safety, from toddlers to so-called Kulturträgers – artists, intellectuals, and scientists on the top of Hitler’s most-wanted list.

The motivation for the Sharps’ heroic work remains a mystery. Perhaps they would have refused the assignment had they known the toll it would take on their marriage and the damage it would cause their children. Upon their return to America, the Sharps’ marriage fell apart. Waitsill left Wellesley, serving in several Midwest churches until his death in 1984. Martha continued doing humanitarian work until she died in 1999, including fundraising for Hadassah and serving as the liaison between the Zionist women’s organization and the liberal Christian community. Her commitment to creating a safe homeland for Jews, particularly children, was unswerving, and witnessing the as-yet-unborn state of Israel as it began to flower in the desert had a profound impact on her.

Martha once said that neither she nor Waitsill saw themselves as anything but ordinary, claiming that anyone in their circumstances would have done the same. Such an explanation characterizes many of those who have been honored in Israel as righteous gentiles. They just did what they felt was the right and decent thing to do.

The story of the Sharps reminds us that when faced with the opportunity to act righteously, we should at least try to make a positive difference in the world.

Rabbi Robert Orkand, who retired from the pulpit rabbinate in 2013, lives in the Boston area. He is immediate past-chair of ARZA, the Association of Reform Zionists of America.

Give to the URJ

The Union for Reform Judaism leads the largest and most diverse Jewish movement in North America.