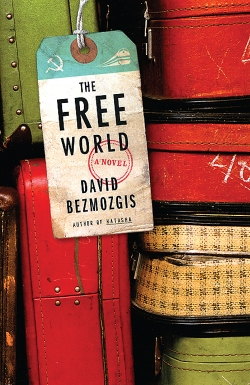

David Bezmozgis, winner of the 2004 Reform Judaism Prize for Jewish Fiction for his story collection, Natasha, returns to the theme of Soviet Jewish immigration in his first full-length novel. The freeing of Soviet Jewry—a cause that captured the hearts and minds of American Jews—generally brings to mind the heroism and sacrifices of the refuseniks who paved the way for other Jews to leave. The characters in Bezmozgis’ novel are Jews who left the Soviet Union when the trickle of emigrants had already become a flood; their heroism resides in their willingness to take a huge chance to make their lives better.

In the summer of 1978, the Krasnansky family is stranded in Ladispolis, a suburb of Rome, along with hundreds of other Soviet Jews waiting for visas to the United States or Canada. The Jews who chose to use their Israeli visas flew directly from Vienna to Tel Aviv. But brothers Karl and Alex Krasnansky, who left Soviet Latvia because of its stagnant economy, hoped to find more opportunity in the West and their parents, Samuil and Emma, came along mainly not to be left behind. In Samuil’s case, the transformation of his life from a respected Party Member to a stateless refugee is devastating, particularly when his medals for bravery as a Red Army captain during World War II are confiscated by a Soviet border guard.

Ladispolis—a seaside town of wooden bungalows and cheap apartments—represents the immigrants’ first heady encounter with the Free World. This is a pivotal moment for a temporary community of refugees, still stunned that they were able to leave the U.S.S.R. and uncertain where they would wind up. In need of cash, many take up dubious jobs, such as self-made tour guides and rental brokers, and shadier ventures, like the auto-body shop that Karl fronts for some Russian thugs. Meanwhile, Alex, a handsome, charming 26-year-old, can’t stop womanizing despite the presence of Polina, his non-Jewish wife who has joined him in exile. Freedom, as Alex will soon discover, carries the burden of responsibility for one’s choices.

While Alex is the prime mover of the plot, the heart of the novel is Samuil, a character who bears the full weight of Soviet Jewish history—under the czars, through the Russian Revolution, World War II, and the Holocaust. A true believer in Communism, Samuil is the kind of man who helped build the Soviet Union; he is also a man with great fidelity to his own values. Watching his wife and his Jewish daughter-in-law, Rosa, recite the Sabbath blessings they just learned from the Lubavitch rabbi, he laments the reversal of “two generations of social progress.” It is clear Samuil will not adapt; in Ladispolis, he spends his days at the Club Kadima, a Jewish community center, in the company of Josef Roidman, a one-legged veteran who was able to keep his medals. “The young generation is quick to criticize,” he complains to Roidman. “It is easy to criticize if you never experienced life before communism.”

Rich in history and understanding, this novel captures images of a transitory community, like an old Kodak movie camera recording an extended family gathering before everyone scatters in different directions.

Bonny V. Fetterman is literary editor of Reform Judaism magazine.

Give to the URJ

The Union for Reform Judaism leads the largest and most diverse Jewish movement in North America.