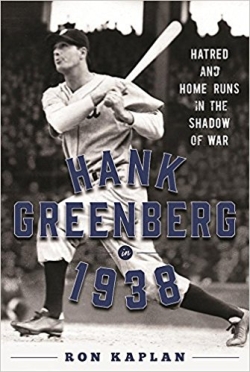

In 1938, Hank Greenberg came three home runs shy of eclipsing Babe Ruth’s record of 60 homers in a season. That same year, Germany annexed Austria and invaded Czechoslovakia, beginning the process of ghettoizing European Jews and setting the stage for the Final Solution. In Ron Kaplan’s new book, Hank Greenberg in 1938: Hatred and Home Runs in the Shadow of War (Sports Publishing), we’re given a time capsule that recounts the entire ’38 baseball season from a Greenberg fan’s perspective, touching on the anti-Semitism he faced, the pressure of the home run chase, and the backdrop of a Europe on the brink of war.

Hank Greenberg had a lot of nicknames — Hammerin’ Hank, Hankus Pankus, Hank the Hammer, and, used more sparingly, The Big Kosher Slugger. He grew up in an observant Romanian Jewish household on the Lower East Side of New York City and attended New York University on an athletic scholarship. From there, he was recruited by major league scouts and eventually landed in Detroit, which was, as Kaplan puts it, “probably the most anti-Semitic city in the U.S.” This was due in part to its most famous resident, Henry Ford, who once “went so far as to publish an edition of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.”

Kaplan’s book is steeped in the old timey-ness of baseball, filled with anecdotes like the Tigers’ owner promising a barber that if his team came back from a 10-run deficit, he’d buy the entire team suits. True to his word, when the Tigers came back to win the game, he bought the whole squad suits to the tune of $125 a pop, a small fortune back then.

Many of Kaplan’s other stories are stark reminders of the hostile racial and ethnic beliefs that were visible at the time. We’re told that Greenberg injured his wrist in 1936 and missed the entire season due to a bigoted player allegedly, “running into him on purpose.” Ben Chapman, a Red Sox player and “unrepentant bigot,” defends his use of racial slurs saying, “Oh, we called [Greenberg] ‘Kike.’ It was all part of the game back then. You said anything you had to say to get an edge.” Though Kaplan asserts that Greenberg never wore his Jewishness on his sleeve, we can imagine in the face of such attitudes, he never forgot it either.

Most of the book’s sources are newspapers of the time, which had their own narratives to craft about the players. As a result, it’s difficult to truly get close to Greenberg. He skipped the ’38 All-Star game, possibly because he sat on the bench behind Lou Gehrig in prior years. Does that mean he was prideful? He wore nice suits and spent as much as $40 on a tie. Was he vain? Kaplan avoids drawing neat conclusions.

What Kaplan does highlight is Greenberg’s importance to Jews of the era as they struggled with unsettling news from abroad and the culture of anti-Semitism at home. Kaplan quotes the Boston Jewish Advocate on the home run chase as it entered its final month: “For the next few weeks, the incidents in Palestine, in Germany, in Czechoslovakia, take a back seat. They are not important. We have had pogroms before; we have had wars before, we have had trouble with the Arabs before. But never before have we had a Jewish home-run king.”

The book’s chapters are divided into months of the ’38 season, with Greenberg’s batting statistics updated at the end of each chapter. As Greenberg gets tantalizingly close to Babe Ruth’s record and the pressure on Greenberg mounts, Kaplan emphasizes the fact that many people in the baseball world didn’t want the record broken at all, especially by a Jew. On the field, Greenberg was walked more and more often. Whether this simply was pitching around a great slugger or something more sinister is up for debate. Greenberg himself, always deferential, simply said, “The reason I didn’t hit 60 or 61 is that I ran out of gas.”

Hank Greenberg in 1938 is, in equal parts, a baseball book and the story of a groundbreaking Jewish athlete. Kaplan has so thoroughly researched his subject matter that one can’t help but feel transported back in time, as if cracking open the morning paper and searching for the box score. It should appeal to baseball fans and armchair historians alike.

Wes Hopper is a writer and reviewer living in Los Angeles.