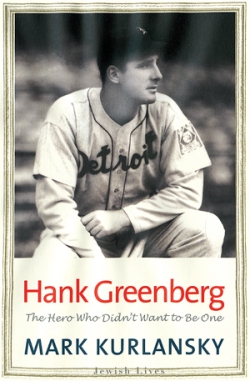

"Hammerin’ Hank" Greenberg of the Detroit Tigers is widely considered the third most important hitter in baseball history, after Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig; he almost beat Babe Ruth’s record for most home runs in a season (with 58 home runs to the Babe’s 60), played on five All-Star teams, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. But throughout his career in the 1930s and 40s, he had to contend with antisemitic taunts on a daily basis from players and spectators. He quickly learned to ignore them and focus on winning instead—advice he later shared with Jackie Robinson, the first African-American on a professional baseball team. Mark Kurlansky, author of this biography in Yale’s new “Jewish Lives” series, regards the 6'4" slugger as a giant for his moral stature both on the field and off.

Greenberg was not the first Jew to play in the major leagues or the only one, but he was the first Jewish superstar in professional baseball. When he decided not to play on Yom Kippur during a pennant race in 1934 and walked into Detroit’s Shaarey Zedek synagogue instead, the congregation gave him a standing ovation. In Detroit, where Henry Ford and Father Charles Coughlin spewed out virulent antisemitism, Greenberg’s stand of solidarity with the Jewish community was never forgotten. “After Yom Kippur, the Tiger first baseman came to be seen as a muscular six-foot-four-inch bulwark against anti-Semitism,” Kurlansky writes. “Fans and reporters started to ignore the real Hank Greenberg in favor of this image of the mythic super-Jew, the deeply religious man who also played baseball very well.”

In truth, 23-year-old Greenberg struggled over the decision of whether or not to play on Yom Kippur. Only ten days earlier, on Rosh Hashanah, he had hit two home runs, for which the Detroit Free Press thanked him with a banner in Hebrew, “LeShanah Tovah, Hank!” But playing on the holiest day in the Jewish calendar was different; rabbis were consulted and even his father weighed in by telling the press, “Henry [Hank] would never play on Yom Kippur!” With all eyes on the most visible Jew in America, in the most antisemitic decade in U.S. history, Greenberg took his place with the Jews.

The irony is that Greenberg was not religious, although he grew up in an Orthodox home in the Bronx, and was never comfortable being cast in the role of a Jewish hero. At age 19 he left New York University after one semester to play professional baseball over the objections of his parents, who regarded baseball players as “bums.” Baseball, as Greenberg recalled in an interview for the American Jewish Committee’s oral history project, was his ticket out of the Bronx and the predominantly Jewish neighborhood of his youth. The son of immigrant parents, Greenberg wanted to “become American as quickly as possible” and pursue the American Dream of financial success and integration in a “wider world” through sports.

The emphasis on debunking the myth of Hank Greenberg as a religious Jew seems somewhat belabored in this biography, but Kurlansky does ably characterize Greenberg’s discomfort with the “super Jew” image. “In a different decade he probably would have been just a great ballplayer, which was all he ever wanted to be,” Kurlansky writes, but Hank was a Jewish superstar in the 1930s when Jews needed a hero. “When Greenberg’s very Jewish face appeared on a Wheaties box,” Kurlansky notes, “it seemed to American Jews that a barrier had been lifted.”

Later in life, Greenberg recognized that “this special role for Jews was a positive thing,” Kurlansky writes. In his posthumously published autobiography, Greenberg himself offered this assessment of his place in history: “It’s a strange thing. When I was playing I resented being singled out as a Jewish ballplayer, period. I’m not sure why or when I changed, because I’m still not a particularly religious person. Lately, though, I find myself wanting to be remembered not only as a great ballplayer, but even more as a great Jewish ballplayer. I realize now, more than I used to, how important a part I played in the lives of a generation of Jewish kids who grew up in the thirties.”

Bonny V. Fetterman is literary editor of Reform Judaism magazine.

Give to the URJ

The Union for Reform Judaism leads the largest and most diverse Jewish movement in North America.