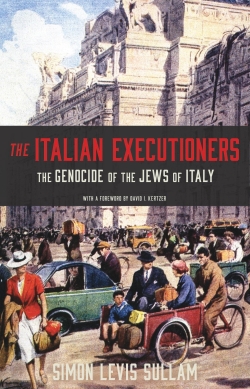

Simon Levis Sullam, who teaches modern history at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, has written a well-researched book that shatters the widely-held belief that Italians were brava gente, “good people,” who protected their Jewish fellow citizens from the horrors of the Holocaust.

The postwar government in Rome nurtured the false belief that the inherent “tolerance” of Italians rendered them incapable of collaborating in “the genocide” of the nation’s Jews. Not surprisingly, this characterization struck a responsive public chord among Italians. Western societies, too, were receptive to the benign, almost comedic image of Italians. The fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, was often portrayed as a strutting buffoon, a farcical refugee of the operatic stage.

In fact, on November 17, 1938, (a week after Kristallnacht took place in Germany and Austria), the Mussolini regime adopted a series of harsh laws that denied Italian Jews their civil rights and removed them from public office and institutions of higher education. Other Fascist laws deprived Jews of their assets, limited their travel, and forbade sexual relations and marriages between Jews and “racially pure” Italians.

The official adoption of those cruel laws was accompanied by a full-throated anti-Jewish propaganda campaign and the publication of a pseudo-scientific manifesto claiming the superiority of “Aryans” over all other “races.”

The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy focuses on the Italian Social Republic (RSI), the Mussolini-led regime supported by the German occupation forces. It was established a few weeks after Italy’s capitulation to the Allies in early September, 1943, and lasted 19 months until the end of the war in 1945. During much of that period, the RSI controlled northern Italy, including the cities of Milan, Venice, Florence, and Brescia.

Because the RSI’s foundational manifesto legally defined Jews as foreigners and enemies, authorities immediately embarked on a program of rounding-up Jews and interning them in Fossoli, a concentration camp 12 miles north of Modena. From there, some 9,000 Jewish prisoners were turned over quickly to the Germans for deportation via railroad boxcars to Auschwitz. Among the 980 survivors was the famous chemist and author Primo Levi (1919-1987).

Since it was frequently difficult to identity who was Jewish and who was not (Jews have lived in Italy for more than 2,200 years), RSI officials offered informers a significant monetary reward for each captured Jew. Sullam notes that informing, “…always involves our closest, even intimate, neighbors…”

Many desperate Jews paid “guides” to shepherd them safely out of RSI territory – usually to neutral Switzerland – but the escapees often were betrayed for a reward.

Expropriation of Jewish property (real estate, art work, furniture, jewelry, rugs, clothing, and much more) was fair game once the original owners were dispatched to Auschwitz. Sullam describes how Mario Cortellini of Venice, who “had supervised most of the seizures of Jewish property… was… put in charge [after the war] of the Office for the Recovery of Jewish Property…. The very person tasked with returning these assets to the Jews who had been his victims.” Sullam found that “Almost 10,000 of the 13,000 people who had already been convicted [of wartime crimes against Jews] or who were still on trial [in 1946] were granted amnesty.”

The Italian Executioners was painful reading for me because my 32 years of international interreligious work took me many times to Italy and the Vatican, where I grew to know and admire many leaders of the historic Italian Jewish community who had suffered such great losses.

Levis Sullam believes Italy “…has moved from the ‘era of witness,’ which placed the victims’ experience and memories in the spotlight, to…an ‘era of the savior’ [of Jews]….It has bypassed the ‘era of the executioner,’ which would have necessitated an examination of the misdeeds of the past – which have now faded into guilty oblivion.”

Sullam’s meticulous scholarship, enhanced by his use of Italian language source material, has cast light on a sordid record of bigotry, prejudice, and hatred that until now has remained largely in the shadows.

With the current rise of overt anti-Semitism in many parts of Europe, Sullam’s book is a powerful call for Italians to confront their troubled past.

Rabbi A. James Rudin is the former head of the American Jewish Committee’s Department of Interreligious Affairs and author of seven books, most recently, Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Stephen S. Wise.

Give to the URJ

The Union for Reform Judaism leads the largest and most diverse Jewish movement in North America.