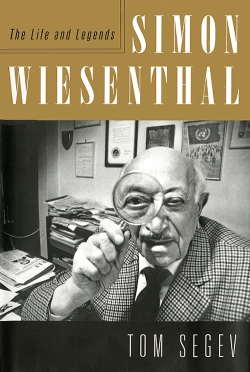

Within days of his liberation from Mauthausen, Simon Wiesenthal gathered the names of more than 150 Nazi criminals he knew must be brought to justice. Over the next five decades, Wiesenthal became the most famous Nazi hunter in the world—the man who located Adolf Eichmann, chief of the Gestapo’s Jewish Department, in Buenos Aires; tracked down Franz Stangl, the commander of Treblinka, in São Paulo; and discovered Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan, “the Mare of Majdanek,” in Queens, New York. Summing up the meaning of his career, Wiesenthal said that when he meets the millions of Jews who died in the Holocaust in heaven, he will say, “I did not forget you.”

“More than anything else, Wiesenthal deserves to be remembered for his contribution to the culture of memory,” writes Israeli journalist Tom Segev in this definitive biography. “Nobody did more than he did in this respect.”

Segev, who had access to previously classified documents, reveals that Wiesenthal worked as an intelligence agent for the Israeli Foreign Ministry’s political department in the pre-state period and for the Mossad after statehood. In the 1950s, however, the Israelis were less concerned with pursuing Nazi criminals than building a nation, and the Western Allies, after a round of war crimes trials, soon became preoccupied with the Cold War. Wiesenthal was angered and frustrated that his leads were ignored. When in 1953 he informed the Mossad that Eichmann was in Buenos Aires, his memo was filed away in an archive. (As Segev puts it, “only the file knew” that Eichmann was in Argentina.) Seven years later, when the Mossad—prodded by tips from a Jewish official in the West German government—captured Eichmann, Wiesenthal’s years of relentless sleuthing finally came to light. With the trial of Eichmann in Jerusalem, Wiesenthal became a cultural icon for the generation that “discovered” the Holocaust in the 1960s.

Running a one-man operation—the Jewish Historical Documentation Center—from his Vienna office apartment, Wiesenthal gave the impression of being at the nexus of a worldwide dragnet. He knew how to approach world leaders and how to work the media. But he was also a lightning rod for attacks from expected sources (Holocaust deniers and neo-Nazis) and unexpected sources—such as the World Jewish Congress, which harshly criticized Wiesenthal for his refusal to join their campaign against former U.N. secretary-general Kurt Waldheim in 1986. Waldheim was running for president of Austria when evidence started to emerge that he had lied about his wartime past. Wiesenthal, however, refused to condemn Waldheim without a thorough investigation to determine whether he had been involved in war crimes. Segev comments: “Wiesenthal’s public stance did not meet the requirements of the sensationalist atmosphere surrounding the affair.” His position, considered a betrayal by some American Jewish leaders, most likely cost him the Nobel Prize.

This insightful biography explores the complex personality of Simon Wiesenthal and gives us a new context for appreciating his legacy: “Ironically, the more years went by and the more unlikely it became that the surviving Nazi criminals would be brought to justice, the more the Holocaust became a universal synonym for evil, a warning sign for every nation and every person,” he writes. “This happened, to a large extent, thanks to the efforts of Simon Wiesenthal.”

Bonny V. Fetterman is literary editor of Reform Judaism magazine.