I have avoided Germany for almost 15 years. My last visit was a business trip in 1985 when I was asked by my studio to help promote a Star Trek film, my first feature film as a director. The visit was modestly successful in terms of helping the film, but I went carrying a lot of emotional baggage about the country and the people, and I was still carrying it when I returned.

Our time in Germany was spent in Munich. One day when I had a break from work, my wife and I were given a brief tour by a young lady familiar with the area and its history. "Here you can see," she said pointing upward, "where some of the buildings have been reconstructed on top...such a shame," she added sadly, "so much damage from the war...a shame for these beautiful buildings." I took this away with me as a testament, a proof that my feelings were valid. Her sadness for the bricks and mortar made me ill. I bit my tongue.

My first invitation to Germany had come in 1968. German TV was carrying Star Trek, and my Spock character was a hit. I was asked to make an appearance on a TV variety show. The invitation had an odor of kitsch about it; I was expected to appear as Spock in full makeup and costume. I wouldn't do it. To appear as Spock outside of Star Trek might have satisfied a certain public curiosity, but I would no more consider it than I would appear as "Hamlet" at public gatherings if I were playing the role in a theatrical production. But I didn't handle it well. I took refuge in the argument that only my personal makeup artist could do the Spock character justice and that would make my appearance impossible. To my dismay, I received a fast response by telex informing me that they would happily pay the cost of bringing the appropriate makeup person. Then they added, "you will come...and you will put on the funny ears." The tone was not only imperious; it was also tasteless! I didn't go.

I was 10 years old when America entered the war in 1941. The four-year struggle had an intense effect on me. My brother and I sold and delivered newspapers all through the period, including Pearl Harbor Day, and I've often wondered if I might have internalized so much of the war because I was in daily contact with the newspaper headlines. Was my family caught up in the physical struggle, or in the Holocaust? Not that I was aware of at the time, but we were part of a strongly identified Jewish community in Boston and my sense of tribal connection was deeply felt. I grew to hate the Germans and their country. I hated their language and delighted in comedy which lampooned their obsession with precision and conquest. Hitler was at once a terrifying power and a good joke. Above all, the plight of European Jews and the need for a homeland where no Jew would be refused entry held a strong place in my heart.

In the late '80s, I came across a story about a Holocaust survivor named Mel Mermelstein who lived in Southern California and had become embroiled in a legal battle against a group of professional Holocaust deniers with connections to David Duke of Louisiana. Mermelstein had won his fight in the Los Angeles Superior Court in 1979 when the judge declared the Holocaust to be an indisputable legal fact. With a co-producer I was able to bring his story to TV, portraying his struggle for justice on TNT. I took great pride in the story.

Two years later I was invited to go to Moscow. A film that I had directed, based on a story I had created on the plight of humpback whales, was being shown there. The Russians were declaring a moratorium on whale hunting and my film was to be part of the World Wild Life Fund commemoration of the event. My parents and grandparents had illegally slipped out of Russia in the early 1900s, and I was eager to see their homeland and touch my roots. Despite the pogroms, I found it difficult to be angry at the Russians because they had stopped the mighty Wermacht at Stalingrad. I accepted the invitation when it was agreed that my wife and I would be taken to Zaslav, the village in Ukraine where my family had lived. The emotional journey culminated in our finding a sizable remnant of the Nimoy tree. Zaslav is close to the Polish border, and my newfound cousins explained that the German military had arrived in town only three days after the German invasion of Russia began. They stayed for three and a half years. The only Jewish men who survived were those who were away at the front as soldiers in the Russian army. It was the first evidence that my family had suffered under the Germans.

In the mid '90s, invitations to appear at Star Trek conventions in Germany arrived with drumbeat regularity and went quickly into the trash. I was intentionally rude and didn't bother to reply. "Been there, done that!" But the drumbeat continued and was accompanied by my Star Trek colleagues' animated reports on the massive German crowds attending the show. My curiosity aroused, I discussed my ambivalence about going to Germany with my wife's cousin John Rosove, our rabbi at Temple Israel in Hollywood. "Do young German fans know that you're a Jew?" he asked. "Perhaps a small number," I replied. "Do they know that you introduced the Vulcan hand salute based on the letter SHIN and that it comes from your experience watching the kohanim (the priestly descendants of Aaron) at synagogue services?" "Perhaps only a small number would have heard about it," I responded. He then said, "If you were to go and tell the story and identify as a Jew, it might have a profound effect. It might be a transforming experience for some of those young people to discover that this person whom they admire is Jewish." And the moment he said it, I knew that I was headed for Germany.

In short time, I made arrangements to attend the convention in Bonn, May 1 and 2, 1999. During the weeks prior to the trip, I began to think about the possible consequences of my decision. I had told the story of the Vulcan salute to American audiences, where it had always been well received, but how would it go down in Germany? Would they feel put upon and resentful? Or might they welcome it as a cleansing opportunity, a chance for healing?

On the morning of April 30, my wife Susan and I arrived in Frankfurt, where we were met by one of the show producers and driven to Bonn. I was scheduled to speak twice, once on Saturday morning and again on Sunday. Since a large percentage of the audience would attend both sessions, it was necessary to prepare two programs. I determined that I would show two behind-the-scenes videos on Saturday and save the SHIN story for the Sunday session. The producers assured me that their projection equipment was capable of playing my U.S. tapes.

On Saturday morning, the auditorium was packed. Every seat was taken and some people were sitting on the floor--over 3,000 fans in all. I handed my tapes to the stage manager and waited for my introductions. Soon the stage went dark and a well-produced collection of video clips appeared on a screen, recapping the highlights of Spock's career in Star Trek. The crowd was enthusiastic. Then it was over and my name was announced. I hesitated backstage, heard the applause, and walked on. Nothing I had been told or experienced could have prepared me for what followed. The applause and cheering rose to a roar, continuing even when I gestured for silence. Cheers, whistling, shouts mingled with rhythmic clapping went on for several minutes. I stood quite paralyzed and deeply touched. Finally the room became nearly silent. I stood still and stared at the audience for a moment, and then they served up more applause mixed with laughter. Eventually they became quiet and I said, "You are so human." The laughter that followed told me that they recognized the Spockian joke, and we were on our way.

I began the session with perhaps ten minutes of Star Trek anecdotes I have told many times over the years, and, to my relief, they had the anticipated effect. When it was time to show the first video, I asked that the house lights be dimmed and gave the start signal. The lights went down, the picture flickered up onto the screen, but it ran at about twice the normal speed! It was unwatchable. The voice sounded like a Mickey Mouse cartoon. I called for a halt. The picture disappeared from the screen and was followed by a tense silence. I was furious, stopped in my tracks in front of 3,000 expectant fans. The seconds ticked by interminably. The audience started tittering. My mind raced for a way to recapture the mood.

When the house lights came up, I asked for questions from the audience. I thought I might buy some time, perhaps a few minutes, until the projection problem was solved, but there would be no video--and the program was about to be taken out of my hands.

The first questions were easily and quickly handled and fell into expected categories. "What did you enjoy most...?" "Did you ever think that...?" And suddenly, someone at a balcony microphone was asking about Never Forget! "Mr. Nimoy, you made a TV show about a man whose family was lost in the Holocaust...." I was caught totally by surprise. I don't think the film ever played in Germany, but fans do find a way to weed out the work. Thanking the questioner, I promised to respond to that question tomorrow. I didn't want to get ahead of myself with the Jewish story, but what I wanted turned out to be irrelevant. Within a few moments someone asked if I would talk about the origins of the Vulcan salute. Was it true that it had Jewish origins? Well, I thought, the time has come. And so I launched into my story.

People have flashed the Vulcan salute to me in all manner of places and circumstances for many years. It began within a week of the first airing of the Star Trek episode titled "Amok Time," in which it first appeared, and it has never stopped. Kids on the street, waiters in restaurants, cops in police cars have offered it, and I salute back. Do they know its Jewish origins? In most cases, no, but this audience now heard the story. I spoke about the Orthodox shul in Boston, of sitting with my grandfather, father, and brother in the men's section during the High Holidays. I described the kohanim wailing their chant under their great tallisim, their hands extended toward the congregation, fingers splayed. I told of my fascination and my peeking in spite of my father's admonition. I told of how I introduced the salute into Star Trek and the Vulcan culture; and each time I demonstrated the gesture there was a blinding blizzard of flash bulbs popping, followed by friendly laughter. And when I was done with the story, the applause went on and on and on. I was moved to tears.

The reaction was at once much more than I expected and greater than I could have hoped for. It was welcoming, enthusiastic, and enormously generous. How could I have so miscalculated? How could my expectations have been so far afield from the reality I encountered? Could this indeed be a new Germany? After all, this audience ranged from teenage to mid-fifties, essentially a post-World War II generation. Could I have prejudged them on a false assumption? In any case, it was I who felt transformed.

On the closing night of the convention, all the celebrity guests were brought on stage to say goodbye and take a final bow. I came out last, and once again the overwhelming roars, cheering, and applause washed over me. I introduced Susan, who also received a wonderful welcome. And then I concluded: "I have been hearing about your generosity and your warmth and enthusiasm. I will take home memories which will be with me for a long time. I am often asked if there is anything I still would like to do. I have been blessed. My hopes and dreams have all been fulfilled. May your lives be full of adventure, may your dreams come true...and may you live as I do, in the warmth of love. Leben sie lange und in frieden... Live long and prosper."

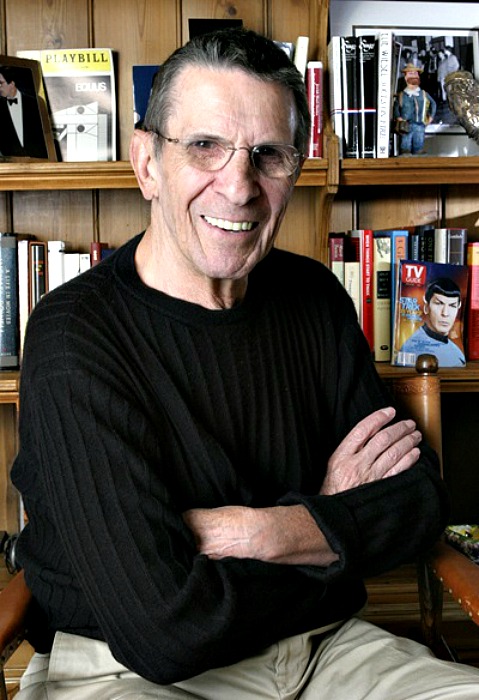

Leonard Nimoy, z"l, was a member of Temple Israel in Hollywood, CA, and an actor, director, and producer of stage and screen. His stage career includes performances as Tevye in "Fiddler On The Roof" and starring roles in "Twelfth Night" and "Camelot." In the mid-50s, he starred opposite Yiddish theater star Maurice Schwartz in a Los Angeles production of Sholem Aleichem's "Hard To Be a Jew." He produced, directed, and starred in a one-man show, "Vincent," about Vincent Van Gogh; other directorial credits include "The Good Mother" and "Three Men and a Baby." In the '50s and '60s, Nimoy appeared on the TV shows "Rawhide," "Wagon Train," and "Perry Mason," among others. His portrayal of Spock, the logical, intellectual Vulcan in "Star Trek," has earned him three Emmy nominations and worldwide fame.

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails