Dr. Yael Danieli, a clinical psychologist, victimologist, traumatologist, author, and lecturer is director of the Group Project for Holocaust Survivors and their Children, which she co-founded in 1975. She served as a founding director of the United Nations of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies and as a distinguished professor of international psychology at the Chicago School of Professional Psychology. I sat down with her to learn more about her pioneering work in understanding and treating victims of genocide and their children.

ReformJudaism.org: What led you to specialize in preventing the long-term and multi-generational effects of trauma?

Dr. Danieli: During the 1960s, while working on my doctoral dissertation on the psychology of hope, I realized that Holocaust survivors and their children suffered from what I would later term the “conspiracy of silence”—most people they tried to speak to about their experiences, including psychotherapists and other professionals, would not listen to or believe them.

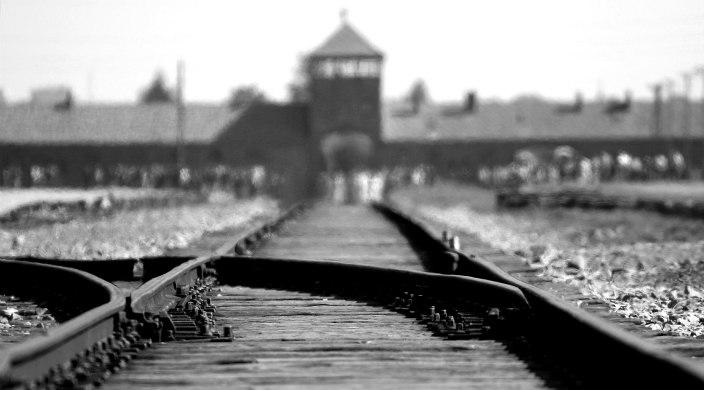

Survivors’ war accounts were too horrifying for most people to hear. Compounding their psychic pain, survivors also encountered the pervasively held myth that they had participated in their own destiny by “going like sheep to the slaughter” and the suspicion that they had performed immoral acts to survive.

The conspiracy of silence intensified their sense of isolation, loneliness, and mistrust of society. In bitterness and despair, many decided there was no one they could talk to about their trauma except, perhaps, other survivors.

Survivor families tended to exhibit at least four adaptational identity styles: victim families, fighter families, numb families, and families of “those who made it.”

In numb families, little or nothing was said about their Holocaust experiences. The children of such families were often too frightened to imagine what could have led to such constriction and lifelessness in their parents. The parents protected each other, and the children protected the parents.

Victim families were characterized by pervasive depression, worry, and mistrust. Joy, self-fulfillment, and existential questions were viewed as frivolous luxuries. Fear of the outside world – of the inevitable next Holocaust – led to clinging within the family. Children were taught to distrust people, especially authority figures, outside the family circle.

Fighter families displayed an intense drive to build and achieve. Parents forbade any behavior that might signify victimization, weakness, or self-pity. Pride was fiercely held as a virtue, relaxation and pleasure were deemed superfluous, and defiance toward outside authorities was sometimes encouraged to the point of peril.

Families “who made it” sought higher education, social and political status, fame, and/or wealth. Some in this group devoted their resources to public acknowledgment and commemoration of the Holocaust, to prevent its recurrence, to ensure that Holocaust victims were treated with dignity, and to aid victimized populations in general.

So many years after the fact, can Holocaust survivors and their children be helped?

Yes. Over time, a fuller understanding of victimization experiences can lead to their gaining the ability to develop a realistic perspective of what happened. That includes no longer viewing themselves and humanity solely based on what happened to them personally during the war.

Recovery also involves a continuous and consistent unraveling and transcending of an individual’s or a family’s adaptation style. Many survivors and their offspring found participating in groups helpful because they could share with others concerns and feelings that would be very difficult to confront alone. Children of survivors have also benefitted from researching the factual events of their parents’ experiences, especially if their parents didn’t speak about the Holocaust or passed on only selective, fragmented accounts.

Is this pathway to recovery unique to Holocaust survivor families?

No. It has been found to be beneficial for victims of other genocides, for children of perpetrators, and for war veterans. Of crucial importance is the empathetic reception of their communities and societies in the aftermath of trauma and tragedy. Societies need to commit to providing measures of acknowledgment, apology, and reparative justice so the trauma becomes a shared rather than a stigmatizing history. The mourning, too, needs to be shared by all, rather than by the survivors alone.

How can we better understand and relate to survivors of trauma and their families?

Listen to them, despite your fear of the terrible things you might hear. To forsake this opportunity is not only to perpetuate the conspiracy of silence and thereby re-victimize the survivors, but to deprive yourself of historic memory that connects you with your own and your people’s history, and allows you to learn from it.

Take the time. You will be forever enriched and grateful for it.

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails