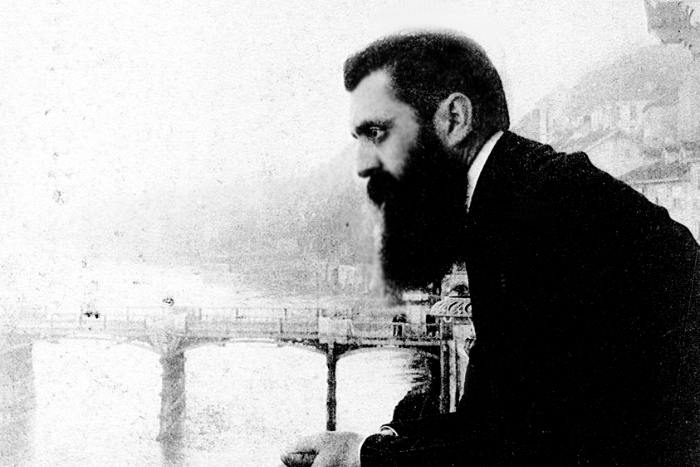

1897. Theodor Herzl leaning over the balcony of a conference center in Basal, Switzerland (E.M. Lilien - The Bettman Archive via Corbis)

Rarely in modern history does a single book change the course of human events. But that is exactly what happened 125 years ago, when in 1896 the Viennese playwright and journalist Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) published "Der Judenstaat" ("The Jewish State"). What makes his achievement all the more fascinating is that Herzl was a thoroughly assimilated Jew.

The story of his transformation into a Jewish national leader and a major player on the global stage of history began a year earlier while he was in Paris covering what became known as "l’affaire Dreyfus" (the Dreyfus affair) for the Neue Freie Presse newspaper.

Like other progressive thinkers of his time, the 34-year-old Herzl admired France’s revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The arrest, trial, public disgrace, and imprisonment of an innocent French Jewish army officer, Alfred Dreyfus, shattered Herzl’s confidence in the ideals and progress of the French Enlightenment.

Captain Dreyfus was, like Herzl, an assimilated Jew. In 1894, he was falsely accused of selling French military secrets to Germany. To Herzl, making a Jewish officer the scapegoat for someone else’s crime reeked of antisemitism. Dreyfus was court-marshalled for treason and stripped of his rank in a degrading public ceremony while the crowd shouted, “A bas les juifs” (“Down with the Jews”). The spectacle was a wake-up call for Herzl, who noted in his diary that the hostile crowd did not shout “Death to the traitor” or even “Death to Dreyfus,” but “Death to the Jews.”

Disillusioned, Herzl concluded that there was no future for the Jewish people in Europe. Antisemitism was not a curable social disease. He wrote in his diary, “We shall not be left in peace.”

After considering a number of solutions, including the conversion of Jewish children en masse to Christianity, Herzl decided that the best course was “…the restoration of the Jewish state.”

Herzl had some doubts about the timing of his revolutionary solution to “the Jewish question:"

“Am I ahead of my time? Are the sufferings of the Jews not yet acute enough? We shall see.”

Any doubts he might have had were short-lived. Once he committed to the idea of a mass emigration of Jews from Europe to their ancestral homeland, nothing would stop him from making his dream a reality. In his words, “If you will it, it is no dream.” Herzl was convinced:

[T]he world needs a Jewish state; therefore, it will arise...No human being is wealthy or powerful enough to transfer an entire people from one place of residence to another. Only an idea can achieve that. The state idea surely has that power.”

In his pamphlet "Der Judenstaat," Herzl outlined his plan for the Jewish statehood in great detail. Some of his ideas reflected his Austrian background. He imagined German as the national language of the Jewish state and proposed the establishment of dueling societies. He was a product a society which, at the time, considered sword fighting to be an ennobling activity.

The publication of "Der Judenstaat" catapulted Zionism into the world arena of Realpolitik.

Herzl met with world leaders to convince them of that solving the Jewish question through emigration was in their self-interest and established the World Zionist Organization to rally world Jewry to his cause. As Herzl was a newcomer to the Zionist idea, his charismatic brand sparked sharp divisions within the Jewish community even as it inspired a revival of almost messianic intensity among many Jews in Eastern Europe and Tsarist Russia, where Jews endured government-sanctioned antisemitism and deadly pogroms.

Herzl knew little about the rich Jewish religious tradition that focused so intensely on a return to Zion – Jerusalem and the Land of Israel. What set him apart was how he was able to majestically (he was always fashionably dressed and sported a long, regal beard) move an oppressed people toward the Zionist goal:

“We shall live at last as free men on our soil, and in our homes peacefully die.”

Herzl was prescient both about the fate that awaited the Jews of Europe and in his prediction that a Jewish state would arise within 50 years of the appearance of "Der Judenstaat." Another Austrian, Adolf Hitler, became Chancellor of Germany in 1933 and launched a campaign to annihilate Europe’s Jews – and nearly succeeded. On May 14, 1948, three years after the Nazi's defeat, Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, standing under a portrait of Theodor Herzl, declared the birth of the State of Israel.

Herzl didn’t live to see that day, but his prediction was off by only two years.

Related Posts

Marking this Moment: Resources for the Release of the Hostages

From Scared to Sacred: Healing Our Collective Trauma in the New Year