More than 100 years ago, Abraham Bezbrosh, my great-grandfather of blessed memory, fled from his home in Russia. He was part of a wave of immigrants that came to the United States of America, in part for economic opportunity, in part to flee persecution. At that time, Jews in Russia endured violent, hateful, state-sanctioned pogroms (terror attacks), and my great-grandfather also fled from a lifetime draft in the czar’s army – part of an unjust targeted recruitment of Jewish boys and young men.

I do not know if his ship passed under the Statue of Liberty or if he ever read the ending of that beautiful poem by Emma Lazarus at Lady Liberty’s base: “Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Even though he came here with empty pockets; even though at the time he spoke not a word of English and always retained a Yiddish accent; even though his faith and culture were different from the “mainstream” – I am sure that he came to know the spirit of those words. Indeed, for his family and for so many others, this land has been a place of refuge.

At night, when I look in on my sleeping children, my heart is full of gratitude for being able to raise them in the United States, a nation that not only gave my family economic opportunity, but also safety and acceptance as members of a religious minority.

Events of the past month have again brought a conversation about immigration to the forefront of our country. And, oh, how my heart has been hurting.

How can I look at my peaceful sleeping children and not see and hear the images and cries of children forcibly separated from parents at our nation’s border? Even though this hateful practice of family separation has been stopped, some 2,000 children remain separated from their parents, and many parents have been deported without their precious children.

Currently, children are being placed in detention with their parents – but this detention is also unacceptable: The American Academy of Pediatrics has stated (in both 2017 and 2018) that children seeking safe haven in the United States should never be placed in detention because of the physical and psychological trauma that children placed in detention experience.

Beyond the harmful effects of these inhumane policies upon children and families, I fear the effects these policies may have upon our nation’s spirit. For undergirding these policies is a fear, a distrust, and sometimes even a hatred of those perceived to be different, or “other.”

As a rabbi, I look to the scripture and thousands of years of Jewish teaching for guidance. In the Book of Leviticus, which was written originally in Hebrew, we read the commandment to love the neighbor as ourselves. We also read the commandment to love the ger as ourselves. That Hebrew word, ger, is sometimes translated through an older English usage as “stranger,” but in our modern usage, it would read “foreigner” or “immigrant.”

Indeed, the commandment to love and treat the stranger with justice is repeated again and again in the Hebrew Bible – at least 36 times, if not 46, according to Jewish tradition. For instance: “You shall not wrong or oppress the stranger, for you were strangers in the Land of Egypt” (Ex. 22:20). Again in Leviticus: “The strangers who reside with you shall be to you as your citizens… for you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (19:34). And in Deuteronomy: “For the Eternal your God… upholds the cause of the fatherless and the widow, and loves the stranger, providing food and clothing -- you too must love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (10:18-19)

Why emphasize loving the stranger, the immigrant? Why teach both – to love the neighbor and the immigrant? Because it’s relatively easy for us to empathize with people who seem, at least on the outside, to be like us. On the other hand, it can take far more effort on our part to understand people who appear to be different from us.

Despite these so-called differences, there is, in truth, no difference in our common humanity. As a Jewish person, this teaches me that we manifest God’s love when we treat neighbor and immigrant alike in our love. Indeed, we turn the immigrant – the outsider – into our neighbor by demonstrating kindness, compassion, acceptance, and justice.

Are not so many of us immigrants ourselves? Or the children or grandchildren or great-great-great-grandchildren of immigrants? Would we not want this neighborly treatment for ourselves and our families? Even if some of the families who come to our nation’s southern border commit a misdemeanor in the way that they try to enter this country, certainly no misdemeanor ever justifies humiliating, inhumane, traumatic, or unjust treatment.

More than this, what happens when we let unfounded fear of one another obstruct our nation’s heritage of acceptance and of fair treatment under the law? Hatred that is allowed to manifest as deed and, and even worse, as law, rarely knows a limit. What then of our precious lamp of liberty beside the golden door?

Want to help families separated at the border? Check out the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism's recent post, "#FamiliesBelongTogether: Update on How to Take Immediate Action," for three ways to help.

Related Posts

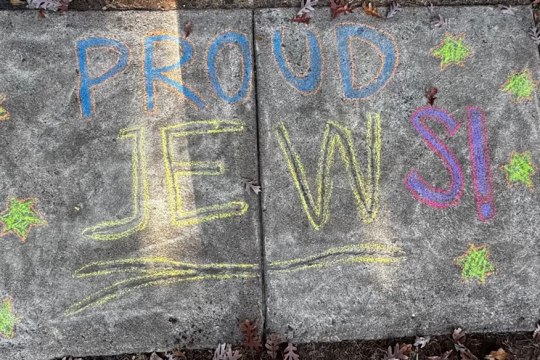

Proud JEWS

Sacred Spaces, Sacred Responsibility: Practical Lifesaving Steps