Maxwell House and the Haggadah

It is perhaps fitting that in the United States, where Jews have found unprecedented freedom, Passover is the one holiday that a vast majority of American Jews celebrate. The level of observance might vary, but the recognition of the significance of our ancient liberation from Egyptian bondage resonates strongly with our own Jewish identity. The account of liberation from Egypt is supposed to be understood and experienced on a personal level, and that is one of the reasons why the Passover meal - the seder - is such an appealing and effective tradition. As with all the major holidays, American Jews have fused their ancient traditions with symbols rooted in the cultural milieu of North America.

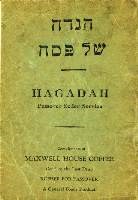

Perhaps the most widely known symbol of Passover in the United States is the Maxwell House Haggadah. For years this popular paperback was distributed as a free gift at supermarkets nationwide. Yet few of us know its origins.

In the 1920s, a New York advertising genius named Joseph Jacobs pursued a program to have big companies market more aggressively in the Jewish community. He approached Maxwell House Coffee Company about advertising in the Jewish press. At this time the coffee company was trying to expand its sales in cities such as New York, which had large Jewish populations. Interestingly, many recent immigrants thought that coffee beans, like other beans, were not kosher for Passover. After consulting several rabbinic authorities, who informed him that coffee beans were technically berries and therefore kosher for Passover, Jacobs began marketing the coffee aggressively during the Passover season. So successful were coffee sales that the Maxwell House company began printing their Haggadah in 1931--a sign of the significance of the Jewish consumer. Thus a mainstay of American Jewish culture was born out of a fusion of two vital instincts: Jewish traditional observance and the desire to succeed financially in the competitive world of American commerce.

Many different Haggadot are used today by American Jews. Some are produced by rabbis and theologians, under the various denominations such as the Central Conference of American Rabbis; some are written by laypeople and represent a variety of ideologies: Black-Jewish relations, interfaith dialogue, and modern feminism. All have one common feature: the reconciliation of traditional Jewish practice with those features of the modern American landscape we consider to be the best.

Dr. Fred Krome is Associate Professor of History at the University of Cincinnati. For more information, visit the American Jewish Archives.