The reading for the Festival of Sukkot comes from Parashat Emor in the book of Leviticus. The very end of the Sukkot portion contains the rationale for the festival of Sukkot, literally “booths.”

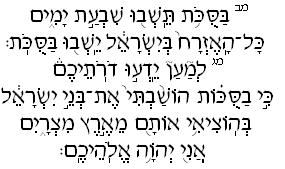

You shall live in booths seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt, I the Eternal your God. (23:42-43)

One challenge we have with this verse is that if we review the account of the Israelites' journey since they left Egypt, we have no record of them living in booths or God commanding them to live in booths. The one mention of “Sukkot” is in Numbers 33. It refers to a specific place: The Israelites set out from Rameses and encamped at Succoth. They set out from Succoth and encamped at Etham, which is on the edge of the wilderness (33:5-6).

Our tradition thus understands the verses above in different ways. “Rabbi Akiva interprets the verse literally—that is, they are huts. Rabbi Eliezer, however, says that the sukkot of the verse refer to the clouds of glory that accompanied the Israelites in the desert” (Strassfeld, The Jewish Holidays, 142). What of the practical question: if they built structures while they journeyed, did they take them down every morning and put them up every night? Some modern scholars note the connection between sukkot and the agricultural aspect over the wandering aspect of the holiday, pointing out that workers lived in temporary huts during harvest time (Strassfeld, 125). Today, these two Biblical verses are interpreted rather literally, and there are many Jews who erect a sukkah and live in them for the entire festival. In Israel and in various other communities, sukkot dot the landscape. Some synagogues build communal sukkot. Rabbinic literature covers in great depth the specific laws pertaining to the building of sukkot, including the design and materials that are permitted and forbidden. Whatever the sukkot were during the time of the wandering, and beyond the rabbinic requirements, the symbol of the sukkah continues to be rich with meaning and significance. These booths are a physical representation of God’s commandment. They are a visual reminder of the exodus from Egypt and of the agrarian society that was prominent during much of Israel’s initial settlement. In addition, they can teach us moral and spiritual lessons: “Rabbi Eliezer [who interprets sukkot to refer to God’s guiding pillars of cloud] sees us as wanderers who need the feeling of that sheltering presence. Rabbi Akiva, on the other hand, is concerned that we are too secure in our shelters and need to recapture some of the sense of insecurity that comes from being wanderers” (Strassfeld, 145). The fragility of the sukkah reminds us of the fragility of life, and the covenant with God that stabilizes us in an uncertain world. In The Tapestry of Jewish Time, Rabbi Nina Beth Cardin teaches us about the symbol of the sukkah:

Sukkot is a holiday of paradoxes: We erect a building to mark the holiday of journey; it is the last in the pilgrimage holiday cycle but comes first, after Rosh HaShanah; and we leave the sturdy shelter of our homes for the flimsy shelter of the sukkah…just as the weather is turning colder (in much of the Northern Hemisphere) and rainy (in Israel). Those paradoxes combine to pose the question: Where is the true shelter in our lives? Is it in the human constructs of bricks and mortar, in the security of walls of wood and locks of steel? Is it found in the consistency of our thinking? in filtering things out? in not letting other things in? in knowing which is which? … Sukkot reminds us that ultimate security is found not within the walls of our home but in the presence of God and one another. … The walls of our sukkot may make us vulnerable, but they make us available, too, to receive the kindness and the support of one another, to hear when another calls out in need, to poke our heads in to see whether anybody is up for a chat and a cup of coffee. … Sukkot reminds us that freedom is enjoyed best not when we are hidden away behind our locked doors but rather when we are able to open our homes and our hearts to one another.”

Sukkot is called “the season of our joy,” Z’man Simchateinu. Being free, feeling joy, takes courage. It is a risk to walk through your fear and experience life. This year, let the sukkah remind you to take that risk and try something new, feel deeply content and sincerely connect with another person.

- In our plugged in, turned on, always daylight, always on-the-run society, what are the merits of having time to live in a sukkah? What are the challenges?

- The sukkah is open on the sides and to the elements. So too is the wedding chuppah, the canopy under which a couple stands to be married. How are these two structures similar in purpose? What can we gain from spending time in either?

- A pilgrimage holiday involving sacrifices in the Temple, the festival of Sukkot was suspended during the exile in Babylon. When the Israelites returned from exile, Nechemiah ( 8:17) describes the entire community rushing to observe Sukkot, building booths and rejoicing. In what way might this holiday symbolize religious freedom?

Related Posts

Dear Israel: A Story of Love and Longing

Becoming B’nei Mitzvah at Any Age