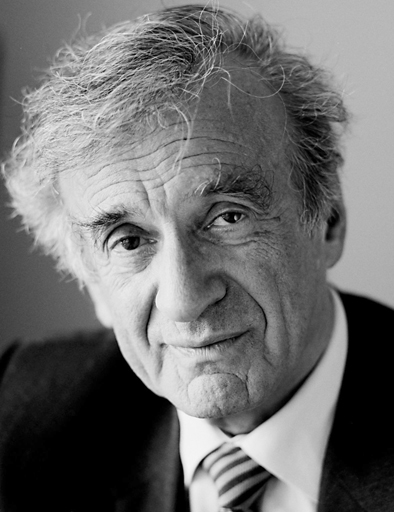

The late author and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel received numerous awards during his lifetime for his human rights activities, including the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1986. A leading voice of the survivor community, he served as founding chair of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council in Washington, D.C. His writing encompasses more than 40 books of fiction and non-fiction, and two volumes of memoirs. In 1986, he and his wife Marion established the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, dedicated to combating fanaticism and hatred in the world.

If there is one imperative that guided Wiesel’s life and work from the time he published his first book, Night, in 1956 until his death in July of 2016, it is this: “I believe that a person who is indifferent to the suffering of others is complicit in the crime. And that I cannot allow, at least not for myself.”

In 2005, I had the opportunity to interview Wiesel for Reform Judaism magazine. Let us contemplate Elie Wiesel's words on the eve of Human Rights Day (December 10, 2021).

Aron Hirt-Manheimer: In awarding you the Peace Prize, Nobel Committee Chairman Egil Aarvik characterized you as "a man who has gone from utter humiliation" to become a "messenger to mankind." Your message, Mr. Aarvik said, is "to awaken our conscience, because our indifference to evil makes us partners in the crime." How central to your thinking is fighting indifference to evil?

Elie Wiesel: One of the central tenets of my life is the teaching in Numbers (19:16): "Lo ta'amod al dam reakha, Do not be indifferent to the bloodshed inflicted on your fellow man." Also in the Bible, Moses rediscovers himself as a Jew and as a man when he defends a Hebrew beaten by an Egyptian and then one beaten by another Hebrew. Had he remained a neutral spectator, he would not have become God's prophet and the leader of his people. Albert Camus expressed this idea eloquently: "Not to take a stand is in itself to take a stand."

You have not only been an outspoken supporter of Israel and Soviet Jewry, but also of victims of injustice and genocide in nations throughout the world. What compels you to take up these causes?

How can I criticize those who were indifferent to Jewish suffering during the Shoah if I do nothing when confronted with the suffering of innocent people today? We Jews suffered not only from the cruelty of killers, but also from the indifference of bystanders.

In your writings and speeches, you have often reflected on the disillusionment of Holocaust survivors upon realizing that telling the world about the Shoah has done nothing to end racism, fanaticism, and injustice.

On June 18, 1981 at the Western Wall in Jerusalem at the closing ceremony of the first World Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, I reflected on our disillusionment:

“We must ask ourselves the painful questions: 'Have we survivors done our duty?' 'Has our warning been properly articulated?' 'Has our message been accurately communicated?' 'Have we acted as true witnesses?' It is with fear and trembling that we often reach the conclusion: something went wrong with our testimony; it was not received. Otherwise, things would have been different…. Had anyone told us when we were liberated that we would be compelled in our lifetime to fight anti-Semitism once more... we would have had no strength to lift our eyes from the ruins. If only we could tell the tale, we thought, the world would change. Well, we have told the tale, and the world has remained the same....

And yet, we shall not give up, we shall not give in. It may be too late for the victims and even for the survivors – but not for our children, not for mankind. Yes, in an age tainted by violence, we must teach coming generations of the origins and consequences of violence. In a society of bigotry and indifference, we must tell our contemporaries that whatever the answer, it must grow out of human compassion and reflect man's relentless quest for justice and memory."

So despite your disappointment and bouts of pessimism, you remain hopeful.

Yes. One must wager on the future. I believe it is possible, in spite of everything, to believe in friendship in a world without friendship, and even to believe in God in a world where there has been an eclipse of God's face. Above all, we must not give in to cynicism. To save the life of a single child, no effort is too much. To make a tired old man smile is to perform an essential task. To defeat injustice and misfortune, if only for one instant, for a single victim, is to invent a new reason to hope.

Just as despair can be given to me only by another human being, hope too can be given to me only by another human being. Mankind must remember too that, like hope, peace is not God's gift to his creatures. Peace is a very special gift--it is our gift to each other. For the sake of our children and theirs, I pray that we are worthy of that hope, of that redemption, and some measure of peace.

Do you still have faith in God as the ultimate redeemer?

I would be within my rights to give up faith in God, and I could invoke six million reasons to justify such a decision. But I am incapable of straying from the path charted by my forefathers, who felt duty-bound to live for God. Without the faith of my ancestors, my own faith in humanity would be diminished. So my wounded faith endures.