Crossing the Threshold

"As soon as you have crossed the Jordan into the land that Adonai your God is giving you, you shall set up large stones. Coat them with plaster and inscribe upon them all the words of this Teaching. When you cross over to invade the land that Adonai your God is giving you, a land flowing with milk and honey, as Adonai, the God of your ancestors, promised you..." (Deuteronomy 27:2-3)

Today when you drive down any highway from town to town or state to state, you pass signs announcing exactly where you are and what the local authorities want known about the place: "Welcome to Aberdeen, MD, Home of Cal Ripken!" "Welcome to New York, the Empire State. The Honorable George Pataki, Governor. Speed Limits Strictly Enforced!" With a placard or a billboard to mark the border, each locality identifies itself, letting you know that where you are now is not where you were only a few moments before.

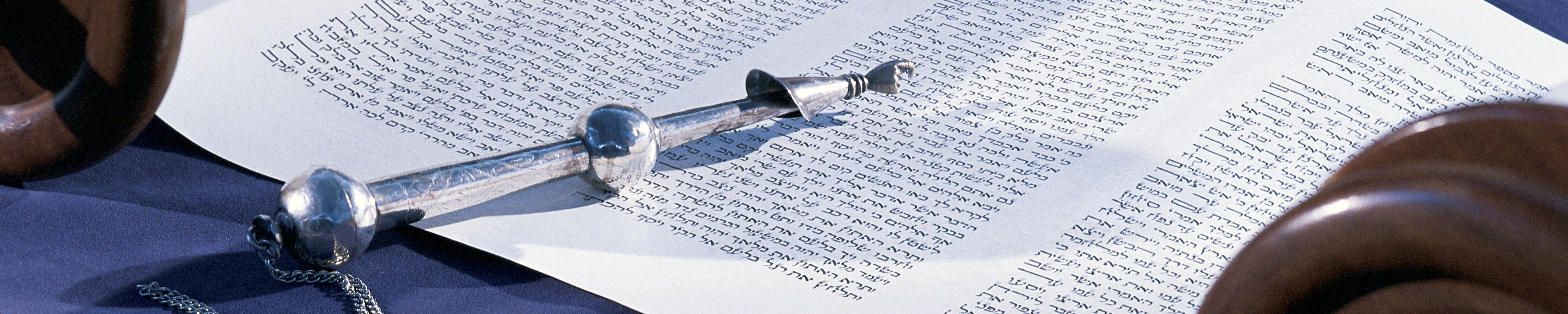

Such is the purpose of the extraordinary "billboards" that this week's Torah portion discusses. According to the Mishnah (Sotah 7:5), each of these stone pillars was inscribed with the entire Torah.

They must have been quite an impressive sight. But the impact on our ancestors would have been far more than merely visual. Imagine the associations made by those passing these pillars as they entered the Land of Israel for the first time. Here were monumental stone inscriptions all could see that were profoundly and mysteriously linked to the stone tablets hidden within the Ark of the Covenant. There stood a statement in stone reminding them that behind them was desert and wandering and before them was a homeland and nationhood. Etched in durable rock was a promise that those who had known the cruelty and injustice of slavery would now live according to an eternal Torah that taught compassion while promoting justice and peace. Perhaps the Israelites would have been most impressed by the inscription of words spoken by God to Abraham in Genesis 15:13-14, 16: "Know well that your offspring shall be strangers in a land not theirs, and they shall be enslaved and oppressed for four hundred years; but I will execute judgment on the nation they shall serve, and in the end they shall go free with great wealth.... And they shall return here in the fourth generation." Carved in stone was God's promise, and before that pillar marched our ancestors, each a unique expression of the ancient promise fulfilled-each and every one of them responsible for maintaining the covenantal obligations to God, who enabled them to cross the border between hope and historical reality.

Not all the borders we cross are so clearly marked, either by road signs or great stone pillars. Yet there are countless experiences in our lives during which we move from one place to another. In those instances, we recognize that we have come to a place we have not been before. Such transitions are not only physical. They can be emotional, spiritual, social, or intellectual. Professor Neil Gillman of the Jewish Theological Seminary refers to the most significant of these instances as "liminal moments." He teaches that as we cross critical thresholds in our lives, ideas, values, priorities, or hopes that are often subliminal (below the level of continuous conscious awareness) come to the fore. It is easy to identify such "liminal moments" with life-cycle events: crossing the border from childhood to adulthood, from single-life to married-life, from being a couple to being parents, from life to death. Every time we cross such thresholds our Judaism provides us with ritual, customs, and celebrations that, like great stone pillars, mark the border. They remind us of where we have come from and where we are headed, linking us with our heritage and history and calling to mind those teachings that will best sustain us in the new territory of our lives.

But lest we think that such moments are limited to life-cycle events, we Jews are provided with other reminders of the thresholds we cross and with symbols to bring to consciousness the Torah teachings that will best guide us. The mezuzah, placed literally at the threshold that separates our homes and other important locations from the rest of the world, brings to mind the values that we obtain within those walls and the values we should carry with us when we venture beyond the boundary of our own gates. As we rise in the morning, crossing the threshold between sleep and wakefulness, the discipline of prayer (with or without the accompanying physical symbols of talit or tefilin) makes each morning a "liminal moment." Our tefilah calls us to a conscious awareness of the sacred purposes that infuse daily living with both meaning and sanctity.

This week's Torah portion, Ki Tavo, includes other accounts of "liminal moments" in addition to the one associated with the great stone pillars. Each depicts a threshold experience in the life of our ancestors that can have resonance in our own life. We could think of the great stone pillars on the border of the ancient Land of Israel as a national mezuzah, marking a threshold in the historical and spiritual experience of our people, impressing upon them the lasting significance of the boundary they were crossing. Upon reflection, we might be able to identify a number of thresholds we ourselves cross every day. We can then create markers for ourselves (mezuzot of one form or another) that transform those occasions into "liminal moments," sacred instances in which we call to mind and consciously apply the teachings of Torah and the wisdom of Judaism and give lasting significance to our own life's journey.

Questions for Discussion

- Can you imagine how our ancestors felt upon viewing the stone pillars and the text of the Torah as they crossed into the Land of Israel? How do you think a non-Jewish traveler might have felt or thought?

- Can you identify some other "liminal moments" described in this Torah portion? Across what borders and over what threshold do the participants pass?

- What do you consider the major threshold experiences in your life? How did you mark them? From where did you receive guidance? What was it? Was it enough?

- How many thresholds do you cross in one day? How do you acknowledge those transitions?

Jack Luxemburg is the rabbi of Temple Beth Ami in Rockville, MD.

The Book of Deuteronomy contains three recurring themes. First, we are reminded repeatedly of the centrality of the tabernacle, which is to be located in Jerusalem. Second, we are confronted with the concepts of reward and punishment. Third and finally, we read of a fervent assault on idolatry. This week's parashah, Ki Tavo (Deuteronomy 26:1-29:8), deals with all these themes in a fairly straightforward way. But in our reading, we also encounter a seemingly benign passage that we must examine in order to determine its relevance to this otherwise cohesive book of the Torah.

In Ki Tavo we are told that after we have harvested our first fruits, we should say the following to God: "We cried to Adonai, God of our fathers, and God heard our plea and saw our plight, our misery, and our oppression. Adonai freed us from Egypt by a mighty hand, by an outstretched arm and awesome power, and by signs and portents. God brought us to this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. Wherefore I now bring the first fruits of the soil that You, Adonai, have given me." (Deuteronomy 26:7-10)

In simple terms, we are being reminded to say "Thank you." Elsewhere in Deuteronomy, we are instructed to thank God after we have torn down the markers and signs of the idolatrous inhabitants of the land that God has given us.

Why must we be mandated to say "Thank you"? And why must we thank God for those things that we seem to have accomplished ourselves? In the question lies the answer. We are reminded in this passage and others like it that we have not accomplished anything if our success was not achieved in partnership with God.

For close to fourteen years, I have worked in the field of education. In that time, I have worked with many families and seen many tears-tears of joy and tears of sorrow. Parents crying for themselves and for their children as they watch their own marriages dissolve. Children living in fear because they lack an understanding of their own handicaps and an ability to see what they could offer the world. Parents learning how to compensate for a child's or their own special learning needs. So many pressures, so many uncertainties that plague the crucial years of a child's development. But we struggle on, and we learn how to compensate for our weaknesses and how to challenge and enhance our strengths. That is not an accident of life: It is an act of God. And for this we must be thankful.

We spend years looking for love. We seek the one person who will support and comfort us during the hard times and share our times of great joy. We fall in and out of love, experiencing much pain and happiness along the way. Yet a marriage ceremony is not a private event: It is also filled with ritual and references to God. Why? Because, as Midrash teaches us, a marriage is not only a partnership between two people: It is also a bond between two human beings and God. It is with the guidance and support of God that we are able to find the person who will love us and care for us for the rest of our days. And so we say "Thank you" to God, our other true partner in life.

When we speak of tikkun olam, we do not claim that we work alone: We recognize that we work in partnership with all humankind and with God. The process of tikkun olam is bigger than any one person, and during our efforts and struggle to repair the world, we should say "Thank you" to God for continuing to be our partner.

Why does this reminder of the importance of giving thanks to God occur in this parashah? Its purpose is to remind us that as we enter this new land, filled with idolaters of all kinds, we must not succumb to the greatest form of idolatry, namely, idolatry of the self. In a critical evaluation of our accomplishments in life, we must never see ourselves alone: We must also see the hand of God and remain humble. In the Book of nevi'im, the prophets are constantly disparaging those who say that they accomplished some feat on their own. We must consciously recognize the existence and constant presence of God.

And when we do, we should say "Thank you."

Aviva Davids, R.J.E. is the director of Education at Sha'arei Am, Santa Monica, CA.

Ki Tavo, Deuteronomy 26:1–29:8

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 1,508–1,537; Revised Edition, pp. 1,347–1,367;

The Torah: A Women's Commentary, pp. 1,191–1,216