This week’s Torah portion, Ki Tavo, presents a choice to the Jewish people. A Jew can follow God’s commandments and be rewarded, or can somehow go astray, risking harsh punishment. Ki Tavo is, in a word, a deterrent. It’s impossible to study Ki Tavo and walk away feeling good about the bacon cheeseburger you ate a couple of weeks ago. However, the supposed result of your indulgence—perhaps years without rain—doesn’t seem to carry a true threat. Not many of us can say we believe our dietary choices are going to affect whether or not we have enough to eat in the years to come. What does Ki Tavo teach us then, by listing these awful punishments, that it’s safe to say will not befall the vast majority of liberal Jews?

Mitzvah. More literally translated as commandment, this Hebrew word is often tossed around instead of the Yiddish word mitzveh, which means good deed. There is a Mitzvah Day at my temple every year, which focuses more on social action than on ritual observance. I participated in the North American Federation of Temple Youth (NFTY) Bay Area Mitzvah Corps this summer, certainly not an experience tailored towards those wanting to continuously uphold the 613 mitzvot of the Torah. Although I know through my Reform experiences that the more precise translation of the word mitzvah is commandment, for many practical purposes within Reform Judaism, mitzvah has meant good deed.

If we consider the mitzvot as commandments, which we can choose to keep or abandon, it is easy to understand the logic between the cause and effect punishment system laid out in Ki Tavo. However, if we consider the laws of the Torah to be good deeds, it seems as if not performing them is the consequence in itself. The kindness of a mundane restriction may be hard to find, but following mitzvot enables us to become better people, in ways we would not have expected. In my confirmation class, Rabbi Adam Spilker likened observing mitzvot to running a marathon: by restricting our behaviors and choosing to adhere to certain traditions, we are freeing ourselves to become better people, just as by training for many months and restricting their behaviors, runners are able to successfully complete marathons.

Translations are interpretations, it is often repeated. The significance of the widely used somewhat inaccurate translation of the word mitzvah within American Reform Judaism says a lot about what we consider important. It is not our duty to abide by every rule, but rather to seek in ritual observance, as in all areas of our lives, ways to become better human beings.

Related Questions

- What if rituals don’t have significance in my life?

There is a wide range of ritual observance within Reform Judaism. Most likely, you don’t need to worry about whether your community will accept the amount of tradition you choose to practice. However, you may be surprised at how observing a simple ritual, even if it seems irrelevant and meaningless at first, can grow to become significant and spiritual.

- Does social action (or our obligation to do good) ever conflict with ritual obligations?

In Judaism, it is likely that you can find something opposing almost any concept or statement. There are times when doing what you truly feel is right may trump observing a tradition, however a lot of times you can find textual support for your righteous action as well. In general, conflict between our ritual and our moral actions isn’t something to worry about.

Taking Action

- Redefine Mitzvah Day…or Rename It

If your youth group is involved with the planning of Mitzvah Day within your congregation, discuss what message the name sends. At my temple, we used to call it “Tzedakah Day” but recently changed the name to “Mitzvah Day.” There is still some concern over the significance of the name. Meet with whoever else would be involved: temple committees, board members, youth groupers…as you plan actions for the day, discuss what kind of event name best showcases the action.

- Look at How You Use Hebrew

Start reexamining how Hebrew is used in Jewish settings you are a part of. We speak a lot about the importance of making sure all participants understand the seemingly hundreds of acronyms used in NFTY regions, youth groups, and camps. The Hebrew words we throw around are also important to think carefully about. Plan a discussion based program in which you examine how translations also provide interpretations. Discuss whether using the word mitzvah to mean “good deed” is a Reform Movement interpretation of the more literal translation.

Food For Thought

What were you taught as the translation of mitzvah in your Jewish education? How does this affect your practice of Judaism?

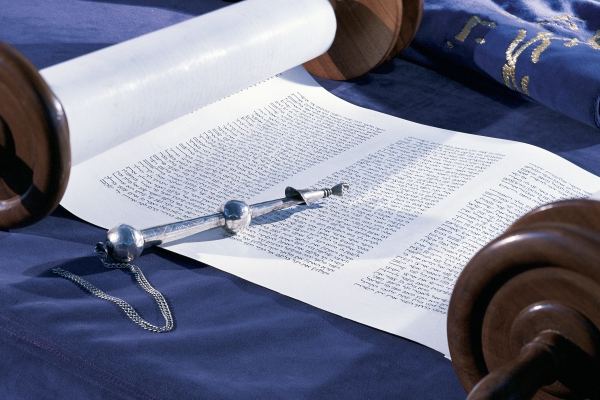

Ki Tavo, Deuteronomy 26:1–29:8

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 1,508–1,537; Revised Edition, pp. 1,347–1,367;

The Torah: A Women's Commentary, pp. 1,191–1,216

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails