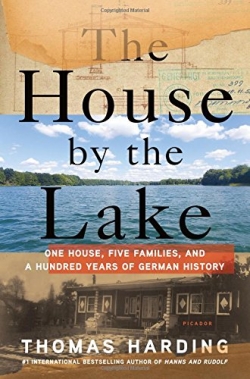

On the outskirts of Berlin lies the charming lakefront community of Groß Glienicke, where locals and summer visitors enjoy swimming, boating and fishing. Nestled among the medieval village’s structures is the lake house where author Thomas Harding’s grandmother once lived. Upon learning of the municipality’s plan to demolish the house, Harding (best known for his bestseller Hanns and Rudolf: The True Story of the German Jew Who Tracked Down and Caught the Kommandant of Auschwitz) sought to rescue it from the wrecking ball. In the process, he uncovered a book's worth of information about each of the five families that previously occupied the house.

His new book The House by the Lake (Picador) begins with Otto Wollank, who purchased a huge tract of land next to the lake in 1890 and gradually shaped it into a productive agricultural estate. In the aftermath of World War I, which decimated the population of working males and the devastating economic impact of the Treaty of Versailles, Wollank resorted to leasing out parcels of land to Berliners looking for a rural escape from the city.

One such family was Harding's great-grandparents, Dr. Alfred Alexander, his wife Henny, and their four children – including Elsie, who would become Harding’s grandmother. The Alexanders were Jews of high status in German society due to Dr. Alexander's service at a field hospital during World War I and his impressive patient list, which included Albert Einstein and Marlene Dietrich. Seeking refuge from the doctor's demanding schedule, the Alexanders leased a parcel of land from Wollank in 1927, upon which they built a seasonal house of dark wood with unique diamond-shaped windows looking out over the lake. It was outfitted with pull-out tables and beds and a large family room. Harding describes the magical effect the house, at once modest and accommodating, had on its guests.

Lakeside life was idyllic for the Alexanders and their neighbors until Wollank died in a car accident in 1929. His son-in-law, Robert von Schultz, a right-wing nationalist, took control of the estate and allowed it to become a training ground for Brownshirts, the Nazi paramilitary wing.

After Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, Jews were gradually barred from their professions. Harding describes the erosion of the rights of Jews through the Alexanders’ experiences – the loss of Dr. Alexander's medical practice and Elsie's inability to practice journalism – and the family's escape to England in 1936, while Germany still was issuing travel documents to Jews.

After the Alexanders’ departure, the lake house became an architectural Forrest Gump, oddly positioned at each major point in German history. Its next occupant was Will Meisel, a renowned composer and music publisher and his wife, Eliza Illiard, a film actress and singer. They first acquired the house through a lease from the Alexanders, and later were able to purchase it through the government's program of Aryanization and the estate manager’s failure to pay back taxes.

As Berlin became the focus of Allied bombing during World War II, Groß Glienicke became a refuge for city dwellers. The realities of wartime soon encroached, however, as a prisoner of war camp was erected near the lake. Realizing that his contributions to popular music were insufficient to exempt him from military service, Will Meisel moved his family to Austria, leaving the lake house in the care of the Hartmanns – a "mixed race" family, Hanns being Aryan and Ottilie Jewish. The Hartmanns were considered "privileged" by the Nazis, due to Hanns' Aryan status and pre-Nuremberg Laws wedding; consequently, they were relatively free from persecution. By the winter of 1944, however, the Hartmanns were out of money, in poor health, and snowed in at the lake house.

A few months later, the Soviet army descended on Germany. As the Red Army approached Groß Glienicke, the Hartmanns and their neighbors hid in pump houses, but to no avail; the younger women were raped, some repeatedly. The Soviet occupation also resulted in the seizure of homes and the disappearance of young men. The isolation Berlin refugees had enjoyed at the lake was now, according to a young resident, "like falling into hell." The Hartmanns retreated on foot to Berlin.

The Meisels returned to the lake house for a brief period, but frustrated by the drawn-out "denazification" process, they returned to Berlin just as the city, like the rest of Germany, was being divided into occupation zones by the Soviets and the Allies. Realizing that the dividing line went right through the middle of Groß Glienicke and that the house, separated from the lake by a fence (later the infamous Berlin Wall), fell to the Soviet-controlled East, the Meisels rented the house to the Furhmanns, a mother and her two children.

The Furhmanns were joined by the Kühne family, headed by Wolfgang, a Stasi agent (East German secret police). After seven years crowded together, the Furhmanns moved and Wolfgang's step-grandson, Roland, let the house fall into disrepair. Plans for its demolition were announced in 2003.

In his quest to save his family home, Harding personalizes more than a century of tumultuous German history by taking us inside the stories of Groß Glienicke families in an objective and non-judgmental way. His depictions are richly illustrated by musical references and engaging dialogue. Most impressively, he brings the lake house at Groß Glienicke to life and makes us care about its fate.

Courtney Naliboff lives, writes, teaches, and parents on North Haven, an island off the coast of Maine. She is a columnist for Working Waterfront, and writes about rural Jewish parenting for Kveller.com.

Give to the URJ

The Union for Reform Judaism leads the largest and most diverse Jewish movement in North America.