The Talmud (Hebrew for “study”) is one of the central works of the Jewish people. It is the record of rabbinic teachings that spans a period of about six hundred years, beginning in the first century C.E. and continuing through the sixth and seventh centuries C.E. The rabbinic teachings of the Talmud explain in great detail how the commandments of the Torah are to be carried out. For example, the Torah teaches us that one is prohibited from working on the Sabbath. But what does that really mean? There is no detailed definition in the Torah of “work.” The talmuidc tractate called Shabbat therefore devotes an entire chapter to the meaning of work and the various categories of prohibited work.

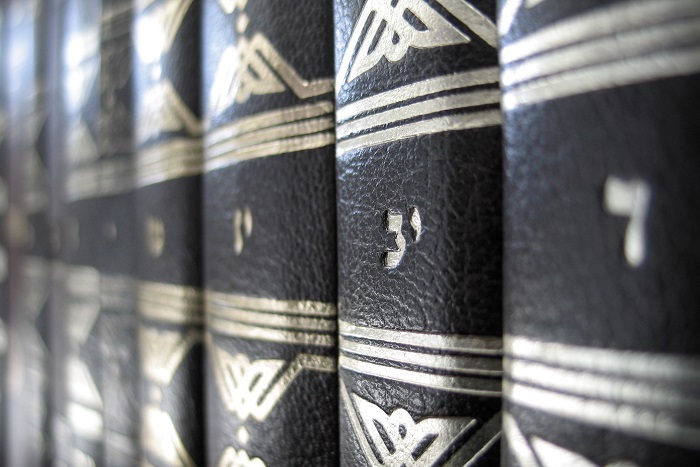

The Talmud is made up of two separate works: the Mishnah, primarily a compilation of Jewish laws, written in Hebrew and edited sometimes around 200 C.E. in Israel; and the Gemara, the rabbinic commentaries and discussions on the Mishnah, written in Hebrew and Aramaic, which emanated from Israel and Babylonia over the next three hundred years. There are two Talmuds: the Y’rushalmi or Jerusalem Talmud (from Israel) and the Bavli or Babylonian Talmud. The Babylonian Talmud, which was edited after the Jerusalem Talmud and is much more widely known, is generally considered more authoritative than the Jerusalem Talmud.

Rabbi Y’hudah HaNasi (Judah the Prince) is thought to be the editor of the sixty-three tractates of Mishnah in which the laws are encoded. The main editor of the Gemara is generally assumed to be Rav Ashi, who spent over fifty years collecting the material. The final revision and editing were most likely undertaken by Ravina (500 C.E.)

The Talmud’s discussions are recorded in a consistent format. A law from the Mishnah is cited, followed by rabbinic deliberations on its meaning (i.e., the Gemara). At times, the rabbinic discussions wander far afield from the original topic. The Rabbis whose views are cited in the Mishnah are known as Tannaim (Aramaic for “teachers”), while the Rabbis quoted in the Gemara are known as Amoraim (“explainers” or “interpreters”). The Talmuds, especially the Talmud of Babylonia, also contain a good deal of aggadah: commentary on biblical narratives, stories about biblical figures and earlier Rabbinic sages, and speculations concerning physical reality and human nature. In short, anything that was of interest to the Rabbis wound up in the Talmud, which in turn became a kind of encyclopedia of the Rabbinic mind.

As books of law, the Talmuds differ greatly from the Mishnah in style and approach. The Mishnah states its rules in a straightforward manner, usually not supporting them with scriptural references or other argumentation. The Talmuds (and this is especially true of the Babylonian Talmud) are dialectical: their predominant form is debate, in which propositions are raised, attacked, refuted, and modified through the give-and-take of argument and counterargument.

Thus for example, if a person wanted to find out about the laws related to Rosh HaShanah, one would go to the tractate called Rosh HaShanah and would find there numerous laws and customs related to the festival. Likewise, if one wanted to find the laws and customs about Shabbat, one could go to the tractate of the same name.

“Correct” answers emerge out of the process of argument that fills the Talmud and all the books written to explain it. They are tentative conclusions whose rightness is based upon the ability of one school of thought to persuade the community of Rabbinic scholars that its point of view represents the best understanding of Torah and of God’s demands upon us.

As the earliest rabbinic interpretation of the Bible, the Talmud is indispensable to understanding the laws and customs still practiced today. The Talmudic discussion and its conclusions provide us with the origins of our many laws and customs. Studying the Talmud can help us search for the many important issues and values that are essential to a thinking and committed Jew. To study Talmud is to take one’s part in the discourse of the generations, to add one’s own voice to the chorus of conversation and argument that has for nearly two millennia been the form and substance of Jewish law.

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails