Avi Hoffman was nominated for a Drama Desk Award for his portrayal of Willy Loman in a Yiddish-language production of Death of a Salesman. He is best known for his award-winning, one-man shows, Too Jewish? and Too Jewish, Two.

We sat down with him to talk about Joseph Papp’s return to his Yiddish roots during the last 2 years of his life.

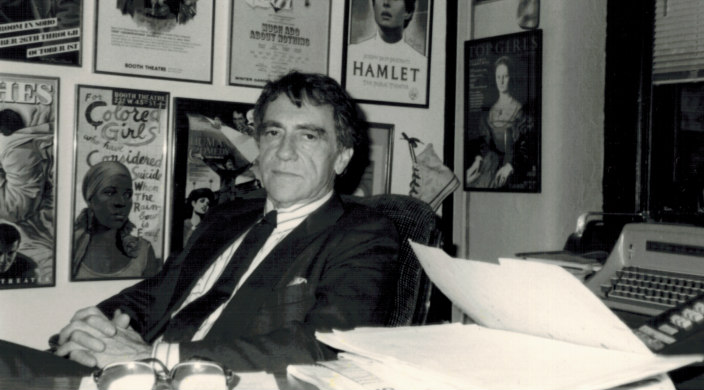

ReformJudaism.org: Legendary Broadway impresario Joseph Papp (1921-1991) is best remembered for creating free Shakespeare in the Park and the Public Theater in New York, for hit musicals like Hair and Chorus Line, and as an activist who saved cherished theater houses from the wrecking ball. What can you tell us about his less known involvement in Yiddish theater?

Avi Hoffman: I had the privilege of working with him in the ’80s, when he re-embraced the Jewish identity of his youth. Born Yossele Papirofsky, he lived with his immigrant parents in a poor section of Brooklyn. His mother, a garment worker from Lithuania, and his father, a trunk maker from Poland, spoke almost no English, which embarrassed their son.

At home, Yossele loved to sing Yiddish songs, and he aspired to become a cantor. Outside, he was sometimes beaten up by antisemites and learned to hide his Jewishness. As he got older, he tried to lose his Jewish accent and changed Papirofsky to Papp, a name many people thought was either British or derived from Greek.

He told his life story at the only concert of his career in 1978, when he sang Yiddish songs at the Ballroom in New York. In his later years, Joe brushed up on his Yiddish, studied Talmud, and connected with many Jewish organizations.

Did Papp share his recovered enthusiasm for Yiddish culture with other theater personalities?

He did. Actor and singer Mandy Patinkin, for example, recalled in an interview how Joe phoned him one day and said, “We're doing this big benefit for the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the Joe Papp Yiddish Theatre, and I want you to come and sing a Yiddish song.”

Mandy said, “I don't know one.” And Joe said, “Oh my God! You have to learn one.” And so he taught Mandy how to sing “Yossel Yossel.”

Joe then convinced Mandy to record an album of Yiddish songs, and thus was born Mamaloshen (Mother Tongue, 1998).

How did the idea of reviving the Joseph Papp Yiddish Theatre project come about?

Joe Papp met my mother, Miriam Hoffman, who was a journalist at the Yiddish Forward. She wrote an article about him, which led to their talking about the idea of creating a Yiddish theater in his name. After several years of developing different pieces, in 1989 he produced and I directed the first modern revolution in Yiddish theater – a show based on Genesis called Songs of Paradise (Lieder fun Gan Eydn). It was about 75 percent in Yiddish and 25 percent in English, featured rock and roll and rap music, a great cast, and enjoyed an eight-month run at the Public Theater.

Sadly, Joe got ill and passed away, and the project was dissolved until three years ago, when Joe’s’ widow, Gail Merrifield Papp, my mother, and I decided to revive the company.

Since then, we've participated in four international Yiddish theater festivals, a production of Death of a Salesman (Toyt fun a Saylsman) in Toronto, Songs of Paradise in Israel, and a Yiddish production of Mel Brooks’ The Producers in Montreal.

How do you respond to those who say Yiddish has no future?

I point out that Yiddish language and culture has become mainstream. You can't turn on a TV without hearing some news anchor use a Yiddish word. Five thousand Yiddish words have been added to the English language in Webster's dictionary.

The largest Yiddish culture festival in North America, the Ashkenaz Festival, takes place every two years in Toronto, Canada. The 2017 Yiddish film, Menashe, won the Critics’ Choice Award at Sundance. The Israeli TV series Shtisel is popular on Netflix. The National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene production of Fiddler on the Roof in Yiddish became one of the hottest tickets in New York.

So I see an enormous hunger in North America and around the world for a thousand-year old culture that not only has survived the Holocaust but, as Isaac Bashevis Singer said when accepting his Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978, “Yiddish is a language of exile without a land, without frontiers, that has not yet said its last word. It contains treasures to be revealed to the entire world.”

When you say Joseph Papp reconnected to his Yiddishkeit, are you referring to the mother tongue, or is there more to it?

To me, Yiddish means Jewish, and kayt means chain – the chain that binds all Jews in the world together. So Yiddishkayt – or Yiddishkeit, if you prefer – relates to everything in the Jewish experience.

For more Jewish arts and culture content, subscribe to the Tuesday edition of our Ten Minutes of Torah series.

Related Posts

Wearing Strength: Jewelry as a Symbol of Jewish Resilience

Nobody Wants This, Season Two: Netflix's Awkward Conversion Class