I caught her before her head hit the ground. It was close, though. She was about to get her blood drawn at a college screening for Jewish genetic diseases. She met with the genetic counselor, understood the procedure and was just sitting at a chair as the phlebotomist readied the materials to draw the four tubes of blood. Her eyes were fixated on the needle; she felt extremely dizzy and slid out of the chair. As she lay on the floor and was able to speak after a few whiffs of smelling salt, she said, “I am OK, but I prefer not to move.” One of my colleagues quickly assembled the privacy curtain, and she remained prone. The phlebotomist kindly kneeled on the ground and drew her blood in the position she desired. It was at this point I realized perhaps why she was so nervous. Many people are squeamish about blood draws, and I have witnessed many patients fainting, but this young lady was different. A young member of her family had just died of Tay-Sachs disease. We rarely hear about Tay-Sachs disease in the Jewish community; testing for the illness has been around since the 1970s, and its presence is virtually eradicated in the Jewish community. To our knowledge, though, the parents of her relative had not been tested.

Much progress has been made in the genetics world, especially in the last decade. In addition to prenatal screening and testing, we have the capability to test for at least 18 other diseases that specifically affect Ashkenazi Jews. Some of these other disorders include familial dystautomia, Bloom syndrome, Canavan disease, and Niemann-Pick, to name a few. Really, we should rename this group of disorders something like “Genetic Diseases That Have Common Mutations in the Ashkenazi Jewish Population,” but that seems a little bit awkward to state. Mutations are changes in a gene that can result in disease, and they can be transmitted to subsequent generations. Jews – specifically Ashkenazi Jews – are predisposed to a group of disorders that can cause devastating illness and even death in early childhood. These disorders have an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, which means that in order for a fetus to be affected, both parents would have to be carriers. Carriers generally do not know they are carriers unless they are tested. In general, everyone has two copies of a gene. Both parents would have to transmit their mutated copy, not their normal copy, to their child in order for the child to be affected. So if both parents are carriers, each pregnancy carries a 25 % risk.

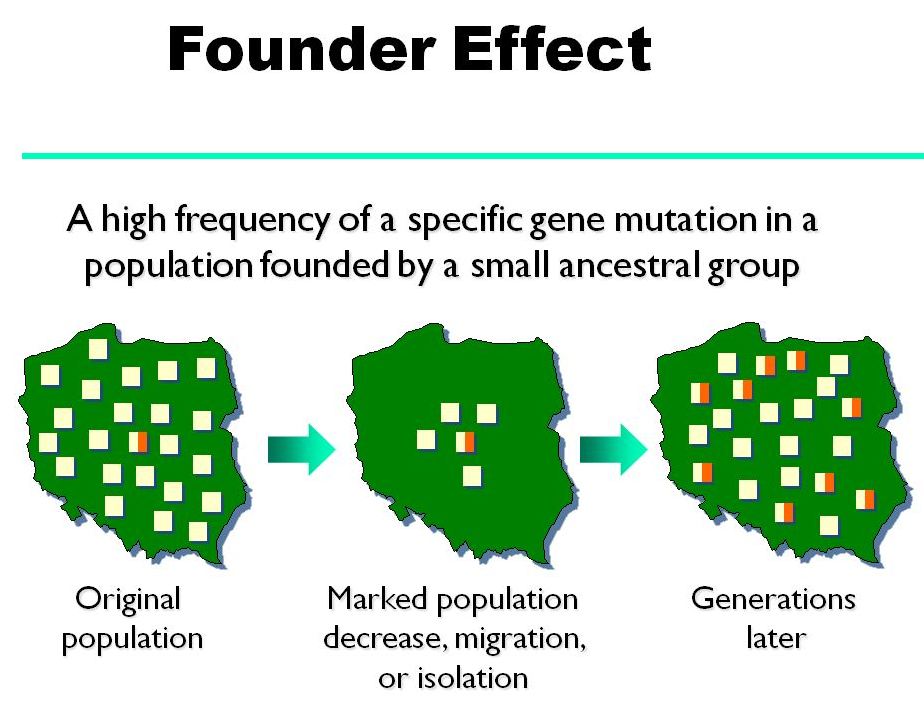

I am often asked, “Why are Jews so prone to so many problems?” A lot has to do with the concept of the founder effect. The founder effect can occur when a population is started with the founder who has a mutation and then that population is severely reduced in size. There are many times in history where Jews migrated and started new populations and, unfortunately, there are many times when the Jewish population was severely reduced. So, when the population is reduced, if the founder with the mutation survives, his mutation is now more prevalent in the reduced population. If the founder passes that “defective” gene on to his or her children, then the children can pass it to the grandchildren, etc. Genetic testing prior to pregnancy is ideal so a couple can be prepared and have the ability to plan ahead. One in three or four Ashkenazi Jews is a carrier for one of these 18+ disorders. Approximately 1 in 100 Jewish couples will be a “carrier couple,” i.e., both carry a mutation for the same autosomal recessive disease. In these cases, medical management options can be discussed with their physician. Today, assisted reproductive technology methods allow carrier couples to have children that do not have one of the known Jewish genetic diseases. I can only imagine that the young woman who fainted was likely thinking of the joy on her relative’s face when her cousin was born and the absolute devastation at the time of diagnosis and profound sadness at the funeral. It’s difficult to imagine these emotions if not experienced firsthand. As Medical Director for the Program for Jewish Genetic Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, I have the privilege of offering screening for patients before pregnancy. Our hope is that families will be able to experience many joyous occasions.

Dr. Susan Klugman is a board-certified obstetrician gynecologist and a board certified geneticist. She is an Associate Professor and serves as the Director of the Reproductive Genetic at Montefiore. In addition, she is the Medical Director for the Albert/Einstein College of Medicine/Yeshiva University Program for Jewish Genetic Health.

Related Posts

The Holy Act of Caring for our Bodies: The Importance of Breast Cancer Testing Early and Often

Navigating Infertility: Resources, Reflections, and Rituals