One of my prized possessions is an illuminated, silver-bound Szyk Haggadah. Until recently, though, I was unaware that its creator, the renowned book illustrator Arthur Szyk, was also known for his scathing political caricatures and cartoons.

A selection of his works are now on exhibit through January 7, 2018, at the New-York Historical Society in Manhattan. “Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art” underscores the Polish-born Jewish artist as a “one-man army” who used his drawing board to battle fascism, anti-Semitism, racism, and injustice during the Holocaust and beyond.

The exhibit features his “Four Sons” illustration from the Szyk Haggadah, in which his depiction of Passover’s “wicked son” bears a strong resemblance to Adolf Hitler. Szyk’s satirical caricatures take aim at the Nazi Fuhrer, Mussolini, Hirohito, and Stalin, picturing them as boorish, cruel masters of evil.

Though Szyk might have thought of himself as “but a Jew praying in art,” as he once said, the Nazis viewed him as a threat – and put a price on his head. Szyk escaped to Canada in 1939 and a year later settled in the United States, where he cherished the freedom to “speak of what my soul feels.”

Szyk, whose mother and brother were murdered at the Chełmno death camp in 1942, used his freedom and artistic arsenal to try to sway American public opinion toward entering the war against Nazi Germany and stopping the annihilation of European Jewry. He was also passionate about advancing the Zionist cause, decrying the British blockade preventing Holocaust survivors from reaching Palestine, demanding an end to racial segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces, and opposing McCarthyism.

His 1946 drawing “Pilgrims” (also known as “Mayflower” and “‘Illegal’ Passenger Ship”) draws a parallel between the Pilgrims’ seeking religious liberty in British colonial America and the Greek ship Smyrna, carrying Holocaust survivors to British-occupied Palestine in defiance of a naval blockade. Syzk decorated the space separating the two ships with symbols of Jewish pride and identity, including a menorah, a large Star of David, and the tribes of ancient Israel.

Szyk’s drawing “And What Would You Do with Hitler” depicts two American soldiers, one Black and one white, pondering what would be a suitable punishment for Hitler. The Black GI says, “I would have made him a Negro and dropped him somewhere in the U.S.A.”

Born in 1894 to a cosmopolitan Jewish family in Lodz, Poland, Szyk left home at the age of 15 to study art at the renowned Academie Julian in Paris. Five years later, while on a trip to Palestine, he was introduced to the Bezalel Academy of the Arts and Design in Jerusalem, dedicated to creating a national style of art blending classical Jewish and Middle Eastern traditions.

The young artist experimented with different styles, but was drawn to the intricate and decorative style of medieval illuminated manuscripts, which remained his signature illustrative method. One of his early works – a 45-page Statute of Kalisz (1929) honoring the 13th-century king’s edict granting Poland’s Jews the right of citizenship – is composed of miniature scenes and portraits, illuminated initial letters, decorative and symbolic border patterns, and calligraphy.

Szyk’s illustrated books often focused on religious themes, including The Book of Job (1946), Pathways through the Bible (1946), The Book of Ruth (1947), and The Ten Commandments (1947). He also illustrated classic secular literature, such as Andersen’s Fairy Tales (1945).

The immigrant artist gained recognition and popularity in the U.S. after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the war. His work now appeared in a variety of leading newspapers and magazines, including the New York Times and Collier’s. One of his biggest fans was First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who described him as a "one-man army against Hitler."

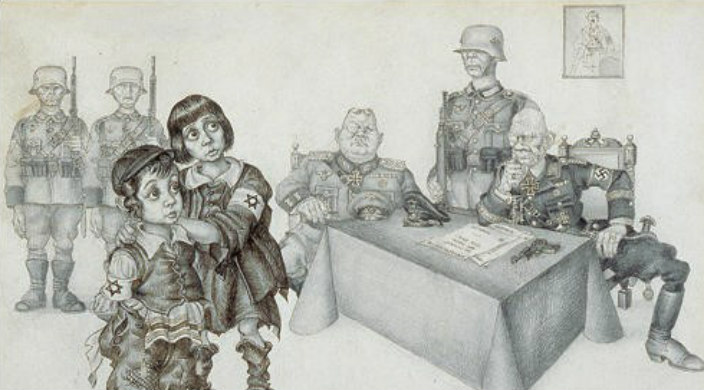

Szyk's 1943 cartoon “To Be Shot as Dangerous Enemies of the Third Reich,” which shows a young Jewish boy and girl in a room before two Nazi officers, appeared on prints and fundraising stamps for the Emergency Committee for the Rescue of European Jewry.

His final campaign sought to expose the excesses of McCarthyism. Like many artists and writers, he was suspected of “Un-American activities.” His membership in organizations such as the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee brought him under suspicion. He naturally fought back with his art, mocking the excesses of McCarthy’s crusade.

Szyk received the Ordre des Palmes Academiques (France, 1923), the Gold Cross of Merit (Poland, 1931, and the George Washington Bicentennial Medal (U.S., 1932). He died at age 57 in 1951 of a heart attack at his home in New Canaan, CT.

Related Posts

This Summer's Hottest Jewish Films and Series

“We Were the Lucky Ones:” Bringing The Holocaust Out of History Books and Into Our Homes