I met Leonard Nimoy in his Beverly Hills office, an unpretentious, spacious room filled with light from wall-to-wall windows which enlivened the memorabilia of Nimoy's long and eclectic career. Nimoy is known in Hollywood not only as an actor of stage and screen, but also as a director and producer.

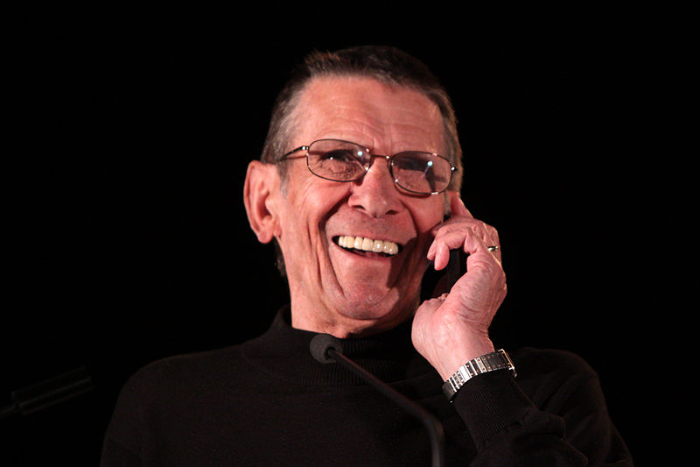

His stage career includes performances as Tevye in Fiddler On The Roof and starring roles in Twelfth Night and Camelot. He produced, directed, and starred in a one-man show, Vincent, about Vincent Van Gogh; other directorial credits include The Good Mother and Three Men and a Baby. In the '50s and '60s, Nimoy appeared on virtually all the top TV shows, including Rawhide, Wagon Train, and Perry Mason. His portrayal of Spock, the logical, intellectual Vulcan in Star Trek, has earned him three Emmys and worldwide fame. For this interview with Reform Judaism magazine, Nimoy was casually dressed in a black sweatshirt and khakis.

Many of us are asking, "How can I express my Judaism and still be involved in the commercial, predominantly Gentile world?" How does one find the right balance? Apparently you have done this - you are an active member of a Reform congregation, and you take your Judaism seriously.

That's right. My wife Susan and I are very involved with Temple Israel in Los Angeles, CA. In fact, the rabbi, John Rosove, is my wife's cousin.

How about your growing-up years? Were you involved Jewishly?

Yes. I grew up in an Orthodox neighborhood in Boston, went to an Orthodox shul, and sang in the choir. We spoke Yiddish at home. I was in AZA (a Jewish youth group) as a kid, and when I was 14 or 15 years old I was performing at war bond rallies run by B'nai B'rith.

I also read Jewish stories on the radio as a teenager. Later I worked with Maurice Schwartz, the founder of the Yiddish Art Theater. In the '20s he staged a dramatization of a play written by I.J. Singer. Schwartz brought I.J. to New York to celebrate the success of the play, and I.J. brought his brother, Isaac Bashevis Singer. And that's how Isaac Bashevis Singer came to America.

Isaac Bashevis Singer's life was in a way a parallel to yours. His parents didn't want him to be a writer; you have said your parents didn't want you to be an actor. What did they want you to be?

They had great faith in me and thought I could be a doctor, lawyer, scientist, chemist -- something with stability. Their lives were so fragile. They escaped from Russia to the United States, not speaking the language. My father was a barber all his life. They were hoping their kids would get educated and live a better life. My brother did. He graduated from MIT and became a chemical engineer. And I set out to be a kind of wandering Jew for a while.

You didn't wander too long, it seems.

It took a while to make a living.

No question, it paid off. Looking ahead, Passover is soon approaching. What kind of Pesach experiences did you have as a child?

I have strong memories of my childhood in Boston, sitting around the kitchen table at my grandparents' house with my parents and my older brother Melvin. I remember a lot of food and candles and wine, pieces of chicken and boiled eggs and matzah, of course, and the . Whoever found the matzah got a quarter. I remember opening the door for Elijah, and that was always a very special, magical moment for me. Those moments in Judaism somehow captured my imagination, those ritual moments that have to do with something mystical.

How do you celebrate your seders now?

We do seders for large numbers of people, friends and relatives, and we invite all the traveling people who aren't connected to a family here in town. Melvin comes with his two sons and a daughter. My daughter Julie and her three children come, and my son Adam comes with his two children.

One year we were planning to get a tent in the backyard and have 70 or 80 people, but I was called away and we had to cancel it. But we're trying to do it again. And my wife is very committed to finding the feminine aspect of these rituals. She reads from a feminist and assigns readings from it.

Do you use different Haggadot at your service?

Yes, we extract from several.

So you create your own service. Do you lead the service?

We split up the service, having different people participate. I lead the service, and so does Melvin -- he's the patriarch of the family.

People at your seder, then, are active participants.

Yes. It's very important to spread the idea that coming out of Egypt, out of bondage, was a liberation process. We need to emphasize that every person is somehow in bondage, so we ask everyone at the seder table to think about what they have liberated themselves from in this past year. What growth, what discoveries have they had? What liberation from previous burdens or commitments or binding concepts that have held them back?

Is there something in your life that was a burden, from which you've been liberated?

Yes, I feel particularly in the past 10 to 15 years I've come out of a cocoon in which I was bound up by obsessive career goals at the expense of personal life. I've lately given myself the license to be much more engaged with my family and our personal activities, and let the career be equal or at best hold second place.

What are some of those activities that you enjoy now?

Taking family vacation and family gatherings, communicating more, being aware of each other more. For years I was so obsessed with work and traveling so much that I missed many aspects of my children's growth. Now each year I try to unbind a little more, spending less time working and more time living a personal life.

Fortunately, I am able to do this, economically. Some people can't. But at least they should be aware that there are great family and life experiences going on that you cannot recapture. You cannot recapture the years, but you can repair and rebuild the quality, and that's what I'm trying to do.

I understand you also write poetry, that in fact, you've written three volumes of poetry. What are your themes?

Mostly love poems. A celebration of love and life. I write from a place of appreciation. I'm about ready to do more poetry. I'm getting close.

Your appreciation of Judaism has also found its way into Star Trek.

Well, the Vulcan greeting in Star Trek is the Jewish hand sign I saw as a little kid at services with my parents - the sign the Kohanim make when they give the priestly blessing. There are some Kabbalistic interpretations of this gesture. Old prints show the hands with various numerological symbols on them, so there's that interpretation. The one I find simplest to relate to is that it represents the "shin," the first letter in the word Shaddai (one of the names for God).

What was it like narrating the new documentary, A Life Apart (about the Hasidim).

I have mixed feelings about the Orthodox. I value the Hasidim greatly as a people. They are in a sense the keepers of the flame. I also liked the people in that movie. I met them, and I felt comfortable with them. But I am very troubled by this horrible issue of "who is a Jew?" I'm very simplistic about it. I ask, if Hitler were here, would he consider me a Jew? And of course he'd say yes, and that's the end of that. If we were all in line to go to Auschwitz, would the Orthodox pull us out of line and say, "You're not a Jew"?

It wouldn't matter.

It wouldn't matter. Exactly. I don't consider myself a politician or a sociologist, but just from the point of view of a Jew, I'm terribly pained by this - what seems to be a flagrant battle for "territory."

What do you think we can do about it?

Oh, it's not the first time we've had this divisiveness; we've had this problem for centuries among Jews, but I think a little common understanding would be helpful, wouldn't it?

Let's talk about your portrayal of Mel Mermelstein in Never Forget (the story of how Mermelstein successfully sued the Institute for Historical Review, which claimed the Holocaust never happened). There is a gripping scene in the film where Mermelstein is being deposed by the lawyer for the opposition. The attorney is mocking and tormenting Mermelstein, who is falling apart in one way, but in another way, he refuses to respond to this obscenity, and he just cries. It's a wonderful, powerful scene. What was going through your mind?

By the time we got to production, I'd spent hours reading the transcripts and depositions. Almost every word in that scene came from the actual transcript. At rehearsal I became caught up in it, and I was really inside this character. A week later we shot it, and it played exactly as we'd rehearsed. I felt touched, angry, moved, speechless -- there was a rhythm, a flow of emotional ideas in the piece that caught me so fully, and I thought, "What's going on here? This man is asking me these questions, teasing me and taunting me...."

The attorney acted like a Nazi. Did you think you would have actual tears? Did you plan it?

I just found myself choking up. I thought it might happen - yes, I did.

You met with Mel Mermelstein many times. How did he strike you?

He's a quiet, soft-spoken gentleman, solid, feet planted on the ground. He was determined to see this thing through, despite a tremendous expenditure of time and money. People told him to let it go, but he wouldn't. And I understood that. I kind of hope that I'd behave the same way if I were in that situation. I admire him. He's another keeper of the flame. I wish "Never Forget" had had more of an audience. I'd be happy to make tapes available to any organization that wants to use it.

You would really give tapes?

Yes. It's a very important story. The revisionists are still at it. And I'm very concerned that the further we get away from the Holocaust, the easier it seems for them to make their case. I'm not one who believes in living in the Holocaust, but I believe it's important that the issue be protected. We can never forget. Never again. That's what the film is all about.

It seems to me that for a long time in this country there was an attitude of "don't rock the boat -- keep a low profile." For example, in the '50s, you didn't go around wearing a Mogen David -- I mean, yes, you were a Jew, but you didn't broadcast it. Was that your experience as well?

Yes, don't make waves. When I came to Los Angeles, into the movie business, I found there was a strong stream of Judaism here. I actually felt more at home here than I had in Boston, where very often people were overtly anti-Semitic.

How so?

People would talk about the "kikes." When I came out here I discovered that it wasn't good for people's careers to be openly antisemitic. So this was a comfort to me, not that I went around promoting the fact that I was Jewish, but it was a different kind of environment, freer and more tolerant.

Do you still travel much?

I've been invited to many "Star Trek" conventions. Lately I've had a number of invitations to go to Germany. I just can't get myself to go. I went once years ago, for an opening of a "Star Trek" movie that I directed. People were very nice to me, but I felt very uncomfortable.

You know, I understand that feeling. I'm from Germany, and I never wanted to go back, but eventually I did go, not as a tourist, but as a missionary, a teacher, so the people can see a real Jew and hear our story.

That's exactly what my rabbi has been telling me, that I ought to go. I really want to think about this further. My rabbi said: go and talk about yourself as a Jew in "Star Trek," and about what you find of Judaism in "Star Trek."

Tell me about that.

"Star Trek" promotes meritocracy, social justice, the values of education, of principles and ideals. These are Jewish values.

You wouldn't want to be involved in anything that doesn't promote these values.

Exactly. When I told Rabbi Rosove that I didn't want to go to Germany, he said maybe I should re-think it, that it might be transforming for those people to see me there.

And maybe it shows the universality of Judaism. I mean, if you can play this far-out person from another planet, and as you said, people do form these strange associations -- why not let it be good for the Jews?

Yes. I'm going to re-think it. It might be good for the Jews.

For more Jewish content, subscribe to the Ten Minutes of Torah series.

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails