Focal Point

- The men went up from there and gazed down upon Sodom, Abraham going along with them to send them off. The Eternal then thought: "Should I hide from Abraham what I am doing?" (Genesis 18:16-17)

- "For I have selected him, so that he may teach his children and those who come after him to keep the way of the Eternal, doing what is right and just, so that the Eternal may fulfill for Abraham all that has been promised him." (Genesis 18:19)

- Abraham then came forward and said, "Will You indeed sweep away the innocent along with the wicked? Suppose there are fifty innocent who are in the city. . . . Must not the Judge of all the earth do justly?" The Eternal One said, "If I find fifty innocent people in Sodom, I will pardon the whole place for their sake." (Genesis 18:23-26)

- And the Eternal rained upon Sodom and Gomorrah―brimstone and fire from the Eternal―out of the heavens, overthrowing these cities and the entire plain, all the cities' inhabitants and what grew in the soil. (Genesis 19:24-25)

D'var Torah

The story of Abraham's discussion with God about the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah is usually described as Abraham bargaining with God. But a close reading of the text shows that God is not bargaining with Abraham!

The discussion begins, after all, with God's rhetorical question, "Should I hide from Abraham what I am doing?" (Genesis 18:17; italics added). The question is not, "Should I hide from Abraham what I am considering doing?" which would suggest that God is open to other possibilities. No, the text clearly tells us that God knows what will happen to Sodom and Gomorrah.

Still, God engages with Abraham in a lengthy discussion about the presence of righteous people among the wicked. Why?

A clue to the answer can be found in the preface to the bargaining discussion. Following that rhetorical question in Genesis 18:17, we continue to eavesdrop on God's thinking, as the Eternal notes that Abraham has been chosen as the source for blessings for all humanity, and further, that Abraham ". . . may teach his children and those who come after him to keep the way of the Eternal, doing what is right and just . . . " (Genesis 18:19).

If Abraham is to teach his descendants "what is right and just" he will have to know those things himself. So God tells Abraham that the wickedness of Sodom and Gomorrah requires their destruction.

Here, Abraham sets himself apart from his ancestor, Noah, who, upon being told that the whole world must be destroyed because of its wickedness, remains remarkably silent (Genesis 6:9-7:5). So instantly Abraham shows his colors, asking whether the innocent should perish with the guilty. Knowing that he himself and his family and entourage are "innocent," and knowing that his nephew Lot and his family are residents of Sodom, he is confident that there are good people among the evil ones of that wicked place.

But he does not ask God to save only the good people. He bargains for the forgiveness of the whole place. And God clearly accepts Abraham's terms, as Genesis 18:26 shows: "The Eternal One said, 'If I find fifty innocent people in Sodom, I will pardon the whole place for their sake.'"

But God says this knowing that there are not fifty good people, nor forty-five, nor forty; in fact, there are not even ten good people in Sodom (Lot, his wife, daughters, and sons-in-law total eight).

The bargaining concludes when Abraham proposes that the cities be saved for the sake of ten righteous people, and God agrees (Genesis 18:32). God departs and the good people (at least those who accept God's advance warning) are saved, but the cities are destroyed, as per the discussion with Abraham. Had there been ten good people, the cities would have been saved.

Interestingly, the saving of the good people was never at issue. The point here seems to be that goodness must reach a critical mass in order to offset the evil around it. The critical mass is apparently ten, the number of people required for a minyan, which represents a Jewish community. But even when that critical mass is not achieved, goodness is preserved and evil is punished.

So, if God knew all along that there were not enough righteous people to save the cities and that the righteous ones themselves would nonetheless be saved, what is the point of the whole discussion with Abraham? It is not to change the predetermined outcome, but rather to offer Abraham the opportunity to demonstrate his own righteousness, by pressing God to save the cities for the sake of the righteous among them.

The God who knew that there were not enough righteous people in Sodom to save it must also have known that Abraham would rise to press the point of justice. Perhaps that explains why God chose Abraham to be the source of blessings for all humanity.

By the Way

- [Robert Alter points out that the term Abraham uses for God, "Judge of all the Earth" echoes the reference to justice in what he describes as "God's interior monologue" that prefaces the actual discussion between the two.] The Judge of all the earth. The term for "judge," shofet, is derived from the same root as mishpat, "justice," which equally occurs in God's interior monologue about the ethical legacy of the seed of Abraham. (Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses [New York: Norton, 2004], p. 89)

- Why does Abraham stop at 10? Perhaps it takes a critical mass to generate an alternative way of living; isolated individuals cannot. The number 10 may be psychologically related to the stipulation of 10 people for a minyan, the quorum for public worship, the point at which an assembly of individuals becomes a group, a congregation. (Harold Kushner, editor of the d'rash commentary, Etz Hayim [New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001], p. 104)

Your Guide

- What does it take to speak out in the face of injustice?

- If God knew that there weren't enough righteous people to save Sodom, and if God knew that Abraham would challenge the justice of its destruction, did Abraham actually accomplish anything noteworthy in his argument? How does this relate to the matter of free will and predestination?

- Did Abraham stop bargaining upon attaining agreement for ten people because he knew that his own family in Sodom only numbered eight? If so, does this discount the positive influence that Lot might have had on his community, the way Abraham is credited with influencing his own community when he left Haran for Canaan (Genesis 12:5)? If so, is this a comment upon Lot's having chosen to live in "sin city" in the first place?

At the time of this writing in 2005, Rabbi Carla Freedman was serving the Jewish Family Congregation of South Salem, New York.

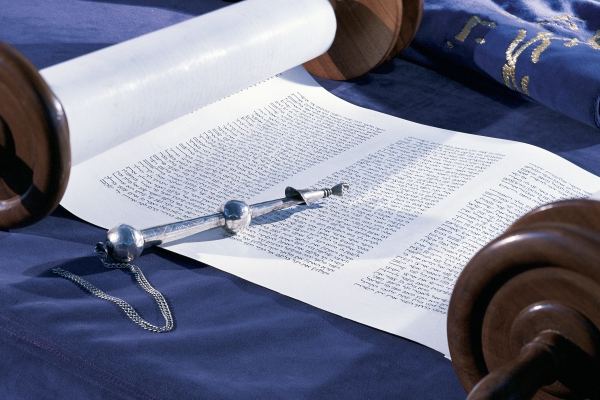

Vayeira, Genesis 18:1–22:24

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 122–148; Revised Edition, pp. 121–148;

The Torah: A Women's Commentary, pp. 85–110

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails