From the moment many students begin college, they (and their parents) are often wondering "What is the right career for me? How can I best use this time at school to prepare for it?" These questions have many layers, as students are wondering how to create economic stability, find work that is interesting and fulfilling, and make the best use of the talents and gifts God has given them. Rev. Dr. Tiffany Steinwert, who is both Stanford's Dean of Religious and Spiritual Life and my friend, bends the question slightly and reflects it back to students beautifully: "Who are you and who do you seek to become for the sake of the world?"

While the lure of especially lucrative, cutting edge, or glamorous careers is understandable, I am always particularly proud of students who choose to focus on public service. Whether they pursue careers as teachers, diplomats, soldiers, healthcare workers, safety officers, lawyers, administrators, or elected officials, these students are answering Rev. Steinwert's question by saying "the best use of my time, talents, and skills are to care for, protect, and defend other people."

My mother was a public school teacher and my father was a family law commissioner, so appreciation for the work of public servants started early and close to home. It expanded immensely during the time I served as rabbi for a congregation in Washington D.C. Hundreds of our congregants were public servants. They worked at every level of local, district, state, and federal government in virtually every agency and branch of service. They voted blue, red, and occasionally green. They were career civil servants of no party and political appointees of both parties. I cannot recall a single one who was not a person of integrity, dedicated to their work and to pursuing the public good to the best of their understanding. Knowing them and hearing about their work regularly made me feel proud to be an American, and especially to serve as one of their rabbis.

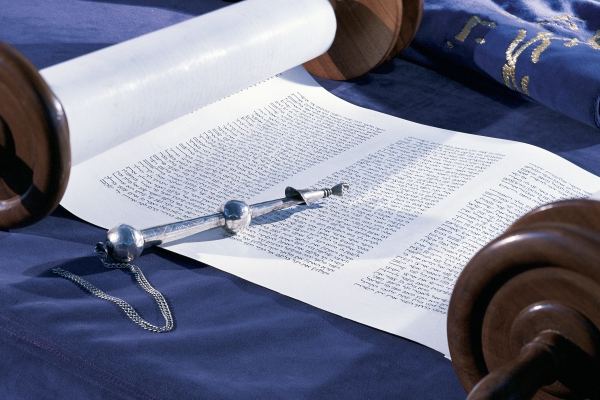

This week's Torah portion, while on its surface largely a reiteration of details of the construction of the Mishkan, is a tribute to public servants like these - -people who honor our trust by performing their jobs with care, transparency, and fear of God. Moses provides the model, as he carefully records each gift given for the building of the Mishkan. He checks his list against the others made by artisans and builders. He then rechecks each entry, ensuring nothing has been misplaced or overlooked. All of this repetition is to provide accountability. In Tanchuma, P'kudei 7, the rabbis say that Moses insisted that his accounting books be public and open to all the Israelites to avoid potential gossip or suspicion.

Moses understood that public officials must be beyond reproach, and that the people needed to trust that the individuals charged with public administration were working in the interests of the community, not for their own personal benefit.

Awareness of the corrupting potential of money and power is at the heart of Jewish wisdom about public administration. Officials of the Temple treasury wore special garments without pockets or long sleeves so no one could suspect them of pocketing public funds. The rabbis were aware that "if such officials become rich, others will assume they have taken money from the Temple treasury themselves" (Shekalim 3:2). The Mishnah further teaches that collecting charity for the poor must be done by at least two people jointly (Peah 8:7). It is to be distributed by a committee of three to assure just criteria and fairness. In the Talmud, we learn that "if collectors of charity must make change or invest surplus funds, they must do so with others present so that no one way suspect them of deriving personal benefit from their transactions"

Integrity in public service was a family affair for the Israelites. The families of the bakers of the bread offering could not give it to their children; the women of the family that prepared the Temple incense never wore perfume, even as brides, so that no one could suspect that they prospered or took advantage of their service to the Temple (Yoma 38).

Maintaining these standards is all the more important for public servants who are already well off. It can be easy to mistake public and private resources, and to lose the public trust by abusing offices for personal gain. Responsible leaders took action to demonstrate that they were beyond reproach. For the rabbis, the core assumption was not that most people are corrupt and therefore no one can really be trusted, but rather that the public trust is sacred and everyone involved, up to and including Moses, must act transparently to preserve it.

In the upcoming spring quarter, we'll be doing what many campus Hillels do - teaching a series for graduating seniors designed to help them prepare for the next stage of adult Jewish life. We will look at this Torah portion to help us talk about the importance of service, sacrifice, and integrity. We will talk about the challenges of being new again, building community, setting up Jewish homes, shifting out of student life and into the working world, managing finances, balancing competing priorities, and the importance of leaving people and places gracefully. We will use Jewish models, including Moses and Aaron, to enrich our thinking. We will all be asking and answering Rev. Steinwert's question: "Who are you and who do you seek to become for the sake of the world?" It's a great question. Just like the Torah, I hope students come back to it again and again throughout their lives. And I hope you do too.

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails