During his lifetime, Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) was frequently confused with another internationally famous photographer: his friend Edward Steichen. So, too, were Stieglitz’s remarkable achievements often overshadowed by the fame of his wife, artist Georgia O’Keeffe.

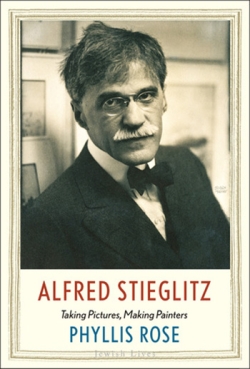

But Phyllis Rose’s book Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters (part of Yale’s Jewish Lives series) brings her subject out of the shadows and into his deserved place in history as the person who made “taking pictures” a respected art form. Rose, a literary critic and a retired professor of English literature at Wesleyan University, has combined her knowledge of photography and modern art with an excellent grasp of the historical trends and events that shaped the artistic world from the Victorian and Gilded Ages to the end of World War II.

Alfred Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey into a wealthy, highly cultured German-Jewish family. His parents had immigrated to the United States from Germany following the failed political revolution in 1848. Alfred’s father, Edward, was a kunstmensch, an art man who “read Schiller, Goethe, and Shakespeare…studied works by Rubens, Rembrandt, and Leonardo…”

Making large sums of money as a wool merchant in America was of secondary concern to Edward, who transmitted to his children the belief that “Art made people better…an idea dealt a terrible blow…when the land of Beethoven became the land of Dachau.”

Many American colleges and universities in the 1870s and 1880s were “notoriously anti-Semitic,” Rose writes. To protect his three sons and two daughters from the debilitating effects of anti-Semitism and for educational purposes, Edward moved his family to Germany.

Seventeen-year-old Alfred spent a year in the city of Karlsruhe to improve his German. He later took courses at Berlin’s Humboldt University with Professor Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, who introduced him to the new field of photography. Thanks to his family’s financial support, Stieglitz was able to spend nearly 10 years in Europe, mostly in Germany and Italy. He returned to New York City in 1890 with no academic degree.

Again, calling upon his family’s wealth, Alfred opened a series of salons and galleries in Manhattan that featured the work of emerging photographers, including William B. Post, Gertrude Kasebier, and A. Horsley Hinton, as well as avant-garde sculptors Auguste Rodin and Constantin Brancusi, and painter Paul Cezanne.

Stieglitz also introduced audiences in the United States and Europe to the paintings of then-little-known modern artists, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Marcel Duchamp. I was astonished to read the remarkable account of how, in 1911, Stieglitz unsuccessfully attempted to interest the Metropolitan Museum of Art in purchasing 81 works by Picasso for $2,000 – only about $25 a piece! The Met’s curator rejected the offer because he was certain the unknown 30-year-old artist would “never mean anything in America.”

The anti-Semitism his father sought to shield him from as a young student was never far from Alfred. In 1935, for example, an American art critic called him “a Hoboken Jew without knowledge or interest in the historical American background.” Stieglitz’s pioneering vision of what constitutes modern art ran counter to conventional thinking. The White Anglo-Saxon Protestant elites who dominated the art scene dismissed him as brash, crass, and disruptive.

The 250-page book includes a generous number of Stieglitz photos, including his best known, “The Steerage,” ostensibly showing Jewish immigrants en route to America, huddled together on the lower deck of a trans-Atlantic steamer. In reality, Rose notes, the ship was actually sailing from New York City to Bremen in Germany, and the crowded passengers, including a man wearing what appears to be a tallit (prayer shawl), were not, in fact, Jews. (Stieglitz himself was traveling first class.)

We also see up-close-and-personal photographs of Stieglitz’s lover and future wife, Georgia O’Keeffe, which, in the 1920s, would have been considered erotic.

In addition to presenting her fascinating biography of Alfred Stieglitz, the author introduces us to some of the history of photography. For example, she gives a detailed description of the intricate process of photography in the years before George Eastman’s creation of photographic film and the invention of the small, portable box camera. Stieglitz’s subjects sometimes had to pose in stillness for three or four minutes in order to create a clear photograph.

Reading Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters gave me a fuller understanding of why Alfred Stieglitz holds such a distinguished place in the American artistic pantheon.

Rabbi A. James Rudin is the former head of the American Jewish Committee’s Department of Interreligious Affairs and author of seven books, most recently, Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Stephen S. Wise. He served as a U.S. Air Force chaplain in Japan and Korea.

Give to the URJ

The Union for Reform Judaism leads the largest and most diverse Jewish movement in North America.