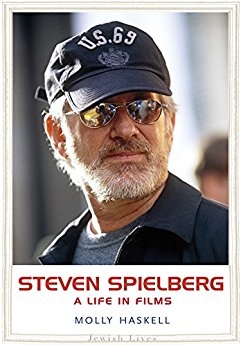

The venerable film critic Molly Haskell may seem to be a curious choice as the author of Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films for the Jewish Lives Series (Yale University Press). As she bluntly puts it in her preface, “I had never been an ardent fan.” Her esteem was reserved for European films, which trade in shades of gray, while genres like science fiction, fantasy, and action adventure were “stay-away zones.”

Despite her misgivings, Haskell slowly unveils a warm respect for the blockbuster filmmaker, discussing his evolution from wunderkind to serious filmmaker through the lens of his very personal struggle with Judaism.

Haskell portrays Spielberg’s early life as a flat-out rejection of his Jewishness. Though he grew up in a strong Jewish community in Cincinnati, OH, surrounded by Jewish immigrants who recounted tales of the Holocaust, Spielberg buried these memories for most of his young adulthood. His mother, wanting to assimilate and join the American middle class, eventually convinced his father to move the family to the “white bread” suburbs of Phoenix, AZ.

In Phoenix, Spielberg discovered his love of movies and moviemaking, a welcome outlet from school, where “he felt more like an outsider than ever, “a wimp in a world of jocks.” His ears stuck out and his nose was too long; bullies called him “Speilbug.” He joined the Boy Scouts, “a place where he found the belonging and fraternity he didn’t find in school or Judaism.” Haskell underlines this turning away from Judaism by mentioning his disdain for Hebrew school and recounting how he spoiled his own bar mitzvah by throwing oranges at guests from the roof.

During his teenage years, Spielberg’s parents became more estranged, eventually divorcing when he turned 19. Haskell explains that although it was Spielberg’s mother who broke up the marriage, he blamed his father, Arnold, for the failed union. Arnold was an engineer and intellectual, but Spielberg viewed him negatively, finding that his “intellectualism was synonymous with wimp, which in turn seemed equated with Jewishness…” Joseph McBride, another Spielberg biographer, is quoted as saying, “Spielberg once said he wanted to be a gentile with the same intensity that he wanted to be a filmmaker.”

Spielberg found it difficult not to infuse his early work with the emotional baggage of his childhood, Jewish and otherwise. In Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, each given their own chapters in the book, Spielberg cast Richard Dreyfuss, who, for the director, “represented the underdog in all of us.” But according to Haskell, Dreyfuss was “a natural Spielberg stand-in: Jewish, smart, hyper, and a rapid-fire talker.” In Close Encounters, Dreyfuss plays a character who seems “out of his element in white-bread America, an alien cut off from his tribe,” much like Spielberg growing up in Phoenix.

If Spielberg’s early films are successful commercially, Haskell is quick to point out that artistically, this wasn’t so. She interjects snippets from her own reviews, which are often critical, penalizing his films for their lack of seriousness.

All this changes with the making of Schindler’s List.

He bought the rights to the book Schindler’s Ark in 1982, but it would take another 10 years for him to make the film, despite appeals from survivors saved by Oskar Schindler. After finally committing to filming, Haskell writes, he “comes home to his rented house, surrounded by Kate [his wife] and his children, he weeps. The film has opened a floodgate of memories and stories, hitherto repressed, of relatives who died or suffered in the camps.” It’s as if he can no longer repress the truth of his own life story, the buried resentments of his childhood give way to a sense of belonging to a larger purpose.

Not necessarily thought to be commercially viable (Spielberg gave up his salary to make the movie), Schindler’s List went on to be a box office and Oscar juggernaut, earning seven Academy Awards and bringing him artistic and international laurels long denied. Haskell sees a different filmmaker from here on, one committed to social justice and civic-minded work instead of just dishing out popcorn fare. In fact, Spielberg took three years off from filmmaking to set up the Shoah Visual History Foundation to document survivors’ accounts of the Holocaust, something he says was “the most important job I’ve ever done.”

From this point forward, the biography touches on his later works of artistic ambition, Amistad, Saving Private Ryan, Munich, and Lincoln; biographer and subject find common ground in Spielberg’s more ethically focused films. Yale University Press has put forward a lively and poignant appraisal of a filmmaker whose embrace of his Jewish identity led to the artistic depth that had long eluded him.

Wes Hopper is a writer and reviewer living in Los Angeles. Read more from him.

Give to the URJ

The Union for Reform Judaism leads the largest and most diverse Jewish movement in North America.