Qian (pronounced Chi-en) Julie Wang is a graduate of Yale Law School and Swarthmore College. Formerly a commercial litigator, she is now managing partner of Gottlieb & Wang LLP, a firm dedicated to advocating for education and civil rights. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times and The Washington Post. She is founder and leader of the People of Color group at New York's Central Synagogue and serves as a member of the congregation's Racial Justice Task Force. Qian Julie lives in Brooklyn with her husband and their two rescue dogs, Salty and Peppers. I sat down with Qian Julie to talk about her acclaimed new memoir Beautiful Country and her Jewish journey.

ReformJudaism.org: It seems ironic that you would choose Beautiful Country as the title of your memoir, given the hard times you and your parents endured as undocumented, impoverished immigrants struggling to survive in America.

Qian Julie Wang: In Chinese, the word for America, Mei Guo, translates directly to "beautiful country." The title at once captures the idealism and the dreams of immigrants who choose to come here and the harsh reality of what it's actually like in America for them and for People of Color. The title captures that duality, that irony, and the grasping on to hope and to the American dream in whatever form one might choose to define it.

The book is dedicated "For all those who live in the shadows: May you one day have no reason to fear the light." Who did you have in mind when you wrote these words and how does it relate to your own experience?

Initially, I was thinking mostly about the undocumented population living in the shadows, but as the book evolved, I realized that phrase has a much broader meaning ; it relates to everyone who is living in the shadows of some early life trauma.

How supportive were your parents in helping you navigate life in your new country?

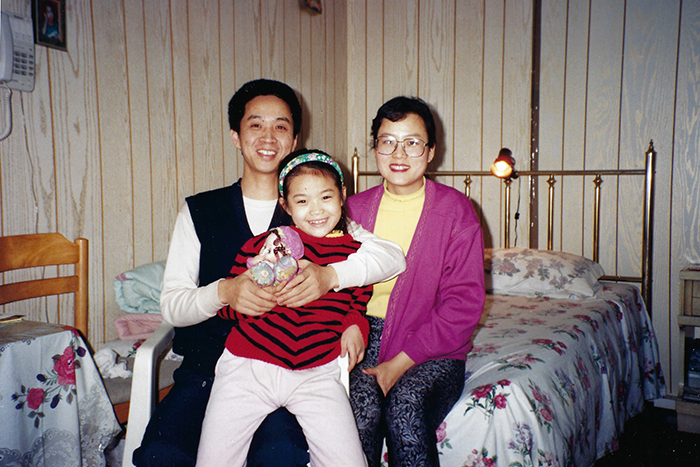

I came with a lot of privilege, the biggest being that my parents had been college professors in China. I was extremely fortunate to have a very strong and willful mother, who taught me from early on that I had agency, that I could create for myself and for us any life I dared to dream of. And while I doubted many things in the world, I never doubted my own abilities.

When I told my mother that I did not see many stories in the library about people who looked like me, she said that maybe one day I could write such a story.

You became a U.S. citizen in May 2016, an election year and a time of escalating rhetoric about undocumented immigrants. How did that confluence of events affect you?

When I became a citizen, 22 years after stepping foot here, I felt that I had a newfound responsibility to speak up and share my story, not because I could speak for the millions of undocumented immigrants, but because I wanted to show the beating heart behind the portrayal of undocumented populations on the debate stage and in the media. Behind hurtful labels like "illegal" are real families with real heartaches, real joy, and real strength. I wanted to remove the stigma.

You and Marc Ari Gottlieb were wed in the archival library of the Brooklyn Historical Society under a chuppah using green books as pillars and a carved Chinese character symbolizing double happiness. What is the significance of these symbols?

That chuppah encapsulates everything that is central to my life: Jewish spirituality, Chinese tradition, and the refusal to let go of happiness and joy, whatever comes our way. Books, of course, are at the center of all of that. They were my friends before I could speak English; they gave me hope and nurtured my dreams.

In an interview for Haaretz, you said, "When I discovered Judaism, I finally felt complete. I realized that I had been Jewish all along. I simply hadn't known it." Is there anything that you want to add?

When I was growing up, one of the books that spoke to me most was The Diary of Anne Frank, which showed me early on that, across conditions, little girls share the same dreams, hopes, and goals. I didn't include Anne Frank in my book because my family had not gone through the Holocaust and I didn't know how much I could own it. I really regret that decision because Anne Frank was the first girl I had found in my beloved books who also grew up in hiding.

The threat to her was much bigger in many ways, but her being marked as illegal because of her Jewishness resonated with me in my undocumented childhood. She was a kindred spirit, and she showed me that I was not a bad girl for wanting little things like toys or an understanding friend, despite living under threat.

Then, the first time I went into therapy as an adult, my therapist gave me a copy of Viktor Frankl's Man's Search for Meaning, and it again resonated with me. I had also read many of Abraham Joshua Heschel's writings because he cared so deeply about social justice. But it wasn't until I went to Central Synagogue and listened to what the rabbi - a Jewish Asian rabbi - was saying on the bimah -- that I realized, Oh, I am Jewish. I am allowed to claim this. My skin color doesn't make me any less American, nor should it make me any less Jewish.

I had always operated according to a certain set of moral principles, but with no spiritual framework. And when I encountered formal Judaism, I found the framework for all the things I was already doing. How wonderful it is to be part of a community that shares one central beating heart and a set of morals to live by.

This past Rosh HaShanah morning, you spoke from the bimah of Central Synagogue and described some of the demeaning comments that you and other Jews of Color have had to contend with in Jewish settings. What inspired you to deliver that message on that day?

I had started a Jews of Color group at Central, and in our conversations realized that my internalized gaslighting -- telling myself things like, "Oh, you're just being too sensitive. No one's staring at you in services. They didn't mean that. They meant well." -- was something all of us Jews of Color were doing over and over. If every Jew of Color that I've met has felt the same thing, then how can it be that we are all uniquely too sensitive?

It is the job of all Jews to speak out against these systemic barriers. Even so, I was not sure if I should start the new year with a message that was in many ways angry, but also very honest. And I never would've had the guts to do it, had I not spoken to Rabbi Angela Buchdahl, the senior rabbi at Central Synagogue, who advised, "People need to hear this. They need to understand. This is a time for reflection and to reflect on it, we need to first be aware of it."

How was the response?

Overwhelmingly positive and supportive. It has given me so much hope for change.