In this week’s Torah portion, Nitzavim, an aspect of the fundamental genius of Jewish existence is illuminated. Three major issues emerge:

In this week’s Torah portion, Nitzavim, an aspect of the fundamental genius of Jewish existence is illuminated. Three major issues emerge:

- What is the meaning of the covenant?

- With whom does God make the covenant?

- What are the roles of Torah—the book of the covenant—and God in the life of the community of Israel?

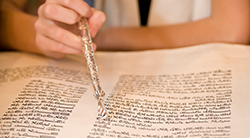

The portion begins with the most dramatic communal ritual since Sinai. In a much more inclusive covenant ceremony, all the Israelites stand together reminded of their journey, of the great blessings, and of their unique relationship with God:

"You stand this day, all of you, before the Eternal your God … to enter into the covenant of the Eternal your God … that God may establish you this day as God’s people and in order to be your God as promised you and as sworn to your fathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob." (Deut. 29:9-12)

Every single person in the community—not just the leaders, but the young and the old, men and women and children, immigrants and the native-born, laborers, and all Israelites—are all called together to renew their relationship with God and to clarify what it means. It is striking that this occurs in Nitzavim, the Torah portion that we read now, right before Rosh HaShanah (and in many Reform congregations, we'll read it again on Yom Kippur) for it portrays a great communal ingathering in which we stand present to renew not only our covenant with God, but also a meta-historical sense of who the community of Israel is and what our role is in it. "And not just with you alone am I reestablishing this covenant.... But with all who are here today ... and all who are not here today" (Deut. 29:13-14, my translation).

The Talmud quotes from this Torah portion in many places, but the most dramatic and famous of them is in a discussion in which different Rabbinic Sages debate the source of their authority. The Talmud explains that "[The Torah] is not in Heaven" conveys that the meaning of the Torah itself is to be revealed and interpreted not (only) by prophets or even by God's miracles, but also by human interpretation and human decision making.

In the famous story of the oven of Achnai (Babylonian Talmud, Bava M’tzia 59a-b), the Sages debate over a new kind of oven and whether it is kosher. One Sage, Rabbi Eliezer ben Hurcanus argues that the oven is ritually pure while the other Sages, including the head of that Rabbinic school, Rabban Gamliel, argue that the oven is impure. When none of Rabbi Eliezer's arguments convince his colleagues, he cries out, "If the halachah (Jewish law) is in accordance with my opinion, this carob tree will prove it." At this point, the carob tree leaps from the ground and moves far away. Of course, the other Sages explain that a carob tree offers no proof in a debate over law. Rabbi Eliezer cries out, "If the halachah is in accordance with my opinion, the stream will prove it." The stream begins to flow backwards, but once again the other Sages argue that one cannot cite a stream—or any other phenomenon of nature—as proof in matters of law. Rabbi Eliezer cries out, "If the halachah is in accordance with my opinion, the walls of the study hall will prove it." The walls of the study hall begin to fall, but the walls are then scolded by Rabbi Yehoshua ben-Hananiah who admonishes them for interfering in a debate among human scholars. Because even the walls of the beit midrash respect Rabbi Yehoshua, they do not continue to fall, but out of respect for Rabbi Eliezer, they do not return to their original places.

In frustration, Rabbi Eliezer finally cries out, "If the halachah is in accordance with my opinion, Heaven will prove it." From Heaven a voice (bat kol) is heard, saying, "Why are you disagreeing with Rabbi Eliezer, as the halachah is in accordance with his opinion in every place that he expresses an opinion?" Rabbi Yehoshua responds, reminding the Sages with the verse from Parashat Nitzavim: "It [The Torah] is not in the heavens that you should say, 'Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?' Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, 'Who among us can cross to the other side of the sea and get it for us and impart it to us so that, we may observe it?' No, the thing [the word] is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart, to observe it" (Deut. 30:12-14).

Rabbi Yehoshua's response confirms one of the most important aspects of Jewish law and life: the work of law is a work of human activity, and we learn this from the Torah itself, which insists upon this kind of human engagement and human authority.

While the Torah may have been revealed in great mystery at a particular time and place, and while throughout most of Jewish history a minority have engaged in its legalistic interpretations, in every age the halachah must be created anew through the human activity of debate and consensus building. This Talmudic passage is often taught to confirm another fundamental aspect of Jewish life and thought: multiple opinions are welcome and important for the process of cultural, legal, and theological development, but some consensus is needed around certain behavioral issues. While the miracles and the drama are enticing, the Jewish community of that time generally followed the ruling of the majority in these kinds of issues.

Ultimately, the renowned Rabbinic Sage Rabbi Yehoshua (an early Rabbinic Sage who lived in the first half-century following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE) affirmed the independence—and even superiority—of human interpretation over and above divine intervention because our biblical text states that it is in fact God’s will that human beings take Torah into our own hands. He brings as his support the statement from our Torah portion Nitzavim that the Torah is “not in heaven” (Deut. 30:12).

The most thrilling part of this text comes when the Talmud asks how God responded to this episode. Apparently, according the Rabbis, upon hearing Rabbi Yehoshua's response that the Torah is “not in heaven,” God smiled and stated, "My children have triumphed over Me; My children have triumphed over Me" (Babylonian Talmud, Bava M’tzia 59b).This famous Talmudic text reinforces three major ideas:

- The covenant is made and remade—or renewed—in every generation, by all of Israel.

- We are not alone: While we stand in God’s presence as individuals, we are also part of a meta-historical collective.

- Not only are we turning simultaneously in three directions as we seek out a spiritual life—toward ourselves, toward others, and toward God; but we also stand simultaneously in three periods of time—the past, the present, and the future. These three periods of time conflate during the High Holidays creating a moment that encompasses all of existence. This idea of standing in covenant with God and with all Jews of the past, present, and future, offers a transhistorical sense of peoplehood—a core principle in the theology of our great teacher, Rabbi Professor Eugene B. Borowitz (1924-2016). As Deuteronomy explains to the Israelites, we never stand before God just in this particular moment. But rather this is precisely the way in which Jews stand within the covenant—not as individuals but as Jewish selves who stand together as part of the Jewish people: “past, present, and future” (Borowitz, Renewing the Covenant: A Theology for the Postmodern Jew, pp. 288-289). And when we do stand together, even and especially as we debate and argue about the big issues of the day, God is smiling.

Rabbi Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi, Ph.D. serves Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion as the National Director of Recruitment and Admissions, and Assistant Professor of Jewish Thought and Ethics. She was also named President's Scholar in 2013. Prior to this appointment, she served as Vice President of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. Rabbi Sabath earned a Ph.D. in Jewish Philosophy at the Jewish Theological Seminary and has co-authored two books and published numerous articles in the Jerusalem Post, the Huffington Post, the Times of Israel, and other venues. She is currently writing a book on covenant theology and co-editing a volume with Rabbi Rachel Adler, Ph.D. on ethics and gender

“I’m not a good Jew.” This is a phrase we hear far too often. I heard it most recently when one of my 11th grade students shared with the group that someone in her high school’s Jewish club had told her she was a bad Jew. “I guess I’m not a good Jew,” she said. This paradigm often assumes that ritual practice is the sole determiner of what makes someone a good or bad Jew. Attend services often, keep strictly kosher, read more sacred texts and you’re a good Jew; by default, you’re a bad Jew if you do fewer of those things. Yet, in Parashat Nitzavim, we see a Judaism that is democratized, allows for different community roles, opens the door for different interpretations, and makes clear what it really means to be a good Jew:

“I’m not a good Jew.” This is a phrase we hear far too often. I heard it most recently when one of my 11th grade students shared with the group that someone in her high school’s Jewish club had told her she was a bad Jew. “I guess I’m not a good Jew,” she said. This paradigm often assumes that ritual practice is the sole determiner of what makes someone a good or bad Jew. Attend services often, keep strictly kosher, read more sacred texts and you’re a good Jew; by default, you’re a bad Jew if you do fewer of those things. Yet, in Parashat Nitzavim, we see a Judaism that is democratized, allows for different community roles, opens the door for different interpretations, and makes clear what it really means to be a good Jew:

“You stand this day, all of you, before the Eternal your God—you tribal leaders, [your head honchos], you elders, and you officials, all the men of Israel, you children, you women, and even the stranger within your camp, from woodchopper to water drawer—to enter into the covenant of the Eternal your God, which the Eternal your God is concluding with you this day, with its sanctions; in order to establish you this day as God’s people and in order to be your God, as promised you and as sworn to your fathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I make this covenant, with its sanctions, not with you alone, but both with those who are standing here with us this day before the Eternal our God and with those who are not here with us this day.” (Deut. 29:9-14)

What is incredible about this opening line is that it tells us that the covenant is not just for the elites; the covenant of the Jewish people is with everyone including leaders, elders, officials, children, adults, millennials, Gen-Xers, Jews of color, those living with disabilities, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, Jews by choice, the rich, the poor, the engaged, the unengaged, the musically inclined, and the not so musically inclined—our people’s covenant with God is available to everyone. This moment of Revelation and truly being present is not just a moment that happened once and will never happen again. Each Yom Kippur, the Jewish community stands, that day, before Adonai our God. Indeed, this idea is reinforced in the Yom Kippur afternoon haftarah, where the people of Nineveh, “proclaimed a fast, and great and small alike put on sackcloth” (Jonah 3:5). By example, this passage reminds us that everyone has access to God, and that all Jews have access and a relationship with God who established a covenant with us.

There is also a tacit acknowledgement in this moment: each of us will establish and interpret the covenant in our own way. Surely, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob had their own interpretation of the covenant with God: Shouldn’t we assume it is the same for each of us, especially if we, the Israelites as well as all future generations of Jews, were all present at the Revelation? After all, think how different people can experience the same event and have widely divergent understandings of that event.

This passage also tells us what it really means to be a “good Jew” by reminding us of our divine purpose. In the Creation story, humans are created b’tzelem Elohim, “in God’s image.” Therefore, our job is to act on our Godly nature by bringing more goodness into the world. To be a good Jew is to do just that—not much more, nothing less. Our tradition’s rituals, practices, and stories help enable us to realize that goal, but they are tools, not an end in of themselves.

As we stand at the entrance to this new year, to this renewed covenant, to our renewed selves, consider this past year, and the High Holidays ahead. For what do you need to do t’shuvah? Who do you need to forgive? Do you need to forgive yourself? This Shabbat, go up to the Shabbat candles and bring the light of Shabbat into your heart. May the light we bring into our hearts sustain us through this High Holiday season. May we truly see everyone in the community, from the greatest to the smallest. And may we all be good Jews.

Rabbi Jeremy Gimbel is the assistant rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel in San Diego, CA. He is also the editor of Birkon Mikdash M'at: Reform Judaism's Bencher.

Nitzavim, Deuteronomy 29:9−30:20

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp.1,537−1,545; Revised Edition, pp.1,372−1,381

The Torah: A Women's Commentary, pp. 1,217–1,234

Seventh Haftarah of Consolation, Isaiah 61:10−63:9

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp.1,618−1,622; Revised Edition, pp. 1,382–1,385

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails