The opening words of Deuteronomy always remind me that Torah has a sense of humor.

Our fifth and final book begins by stating, “These are the words that Moses addressed to all Israel on the other side of the Jordan” (Deut. 1:1). The Hebrew name for Deuteronomy, D’varim, literally means “words,” and this framing sets the entire book apart from the rest of the Torah.

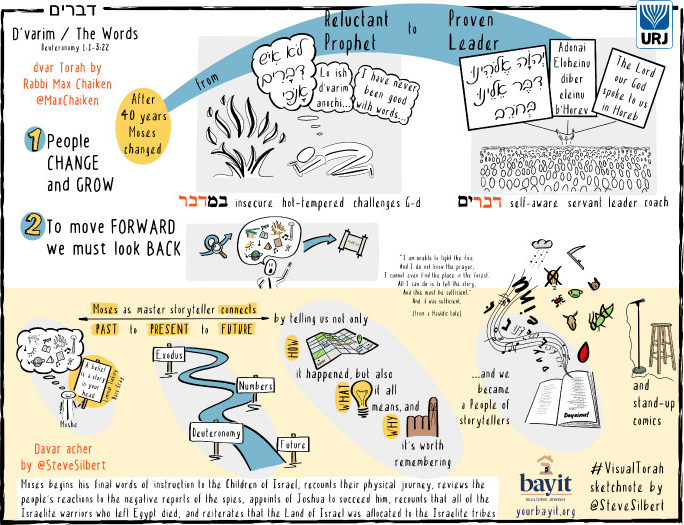

In the previous three books, everything we have seen and heard about Moses has been in the third person, but here, Moses ostensibly speaks for himself. The humor comes from what we know about Moses: In his encounter with God at the Burning Bush, the reluctant prophet needed serious convincing that he was the right man for the job. He pleaded with the Eternal One:

“I have never been good with words, either in times past or now that You have spoken to Your servant; I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.” (Ex. 4:10)

Now here Moses stands, 40 years later, ready to speak an entire book called “Words,” including its first portion, which is also called D’varim. After 40 years in the desert, Moses has found his voice.

Of course, the biblical scholars among us justifiably understand Moses here as “no more than a literary device for supporting the thread of injunction and narrative” (William W. Hallo in The Torah: A Modern Commentary, rev. ed., p. 1,149). The rest of Deuteronomy contains legal material mixed with impassioned sermons, all carefully crafted to reinforce the importance of maintaining the covenant with the Divine, formed at Sinai, with all the people Israel. So, framing the book as Moses’ words certainly would have been a smart choice of the author (or authors) if their goal was to imbue those laws and sermons with prophetic authority.

Yet even if it is a mere literary device, we can still learn from the conceit of the humble prophet who was “never good with words” standing on his soapbox, speaking directly to the people Israel, as we stand ready to move forward.

A first lesson relates to personal growth. Moses’ role as the speaker, if we can suspend our scholarly disbelief, reminds us that people change and grow. Forty years in the desert leading an unruly, cranky bunch of Israelites would take a toll on anybody. Yet even given the difficulties of leadership and prophecy, Moses manages to cultivate and deepen his skills. Even through the personal tragedies of mourning his siblings, Miriam and Aaron, he found a well of resilience within himself, and he turns his weakness with words into a profound way with them.

A second lesson in this portion reminds us that in order to move forward, we sometimes must start by reviewing where we’ve been.

The heart of this portion offers an abridged retelling of the Israelites’ journey through the wilderness. Starting from Horeb (Deut. 1:6), he reminds the people of his own challenges of leadership, and his need to delegate and maintain order (Deut. 1:9-18). He recounts the deep uncertainty and fear the Israelites expressed, leading to the episode with the spies (Deut. 1:22-24) and eventually to God’s decree that the people would remain in the wilderness for an entire generation (Deut. 1:34-38). Finally, Moses turns his attention to review the recent military history of the Israelites’ wanderings. He recounts for the people both the defeats and the victories in their encounters with neighboring tribes and peoples over the course of their trek through the desert (Deut. 1:46-3:22).

In all of this retelling, though, Moses never fails to lose sight of what comes next: crossing the Jordan and entering the Promised Land. He carefully reminds the people that “the Eternal your God has been with you these past 40 years” (Deut. 2:7). The way he crafts the story offers constant reminders that their defeats coincided with their lack of trust in God and their victories were delivered with God’s help.

Sometimes I struggle with these accounts of military battles in our sacred text. I try not to dismiss my own discomfort, but I also try to find the wisdom in Torah and remember that it may have something to offer us today. I’m struck this time not by the particulars of each military engagement, but by the way Moses retells the story to the people as they prepare for the march forward. Their trust in themselves, like their trust in God, grows as Moses reprises for them all that they have already experienced. He accomplishes his goal of girding the Israelites spiritually for the challenges to come by reminding them of all that they have already endured and survived.

This can be a powerful lesson for us, too. While we hopefully do not find ourselves fighting literal battles, each of us faces struggles and challenges in our lives. Each of us will encounter self-doubt or despair, or feel vulnerable to attack; you may even be feeling that now.

Yet like our Israelite ancestors, we need not fear. Instead, we can try to follow Moses’ lead.

As he grew to overcome his fear of words, we too can remember and identify ways we have grown, and weaknesses that we’ve turned to strengths. Like Moses, we too can look back and consider our journey before we advance. We can choose to retell our story in ways that remind us that we are not alone, and that we too have the power to move forward from strength to strength.

In D’varim, the first portion in the Book of Deuteronomy, Moses has found his voice after 40 years in the desert. He has matured from one who asks his brother to speak for him to one who is fully ready to lead his people, and capable of doing so. He’s experienced personal growth and has learned that to move forward you have to look back.

As the affirmed leader, Moses could have simply said “Go over there and settle down, build a nation, and follow the rules I’ve already laid out.” The people might have done just that, the Book of Deuteronomy could have been much shorter, and there would probably be no Jewish people around today. Long ago, they would have taken the facts and created their own story to make sense of the facts.

But Moses chose to shape the development of the Jewish people by telling his story. In Liminal Thinking: Create the Change You Want by Changing the Way You Think, Dave Gray writes that “a belief is a story in your head.” When we tell stories we’re doing more than sharing facts, we’re building relationships - shared beliefs and visions - between storyteller and audience. As a leader, Moses shares the facts with all of the context of places, situations, failures, and successes. Moses tells us a story to give meaning to them. He shares a belief and a vision in terms of what happened, what it all meant, and why it was worth remembering. He connects the past to the present and the present to the future. In doing so, he teaches us to be a people of storytellers; it’s who we are and what we do as a Jewish people. Arguably, it’s what makes us a distinct people, even with all of our diversities.

In Exodus, we become a free nation and build a house (the Mishkan). In Leviticus, the house rules are laid out for us. In Numbers, we walk the dirt tracks in the wilderness growing and searching for home. The Book of Deuteronomy plays out in that liminal moment where we stand on bank of the Jordan River as neither the Children of Israel of the past nor the People of Israel of the future. Moses tells us a story that gives us a shared experience, gets us out of the dirt tracks of the wilderness, and emotionally engages us to pave the road to the Jewish future.

We tell that story every year at Pesach to keep us fired up to build the Jewish future. We tell that story every morning when we say “I am the Eternal your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt to be your God. I am the Eternal your God.” We tell that story to remind us that only by looking back can we build forward.

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails