Biblical and rabbinic sources make clear that there is something about Joseph that exceeds regular categories. The biblical text depicts him as an over-the-top storyteller or actor who publicly reports on his dreams and stages conflict by bringing "evil reports" to his father about his brothers (Genesis 37:2). His very name ("Yosef") connotes addition or supplement. Despite (or perhaps because of) his tendency to spy on his brothers and tell grandiose dream-tales, Joseph is adored by his father. Jacob gives him a fancy costume to wear for his various "performances": the kutonet passim (Genesis 37:3), a striped cloak that is designated elsewhere in the Bible as the garb not of princes but of princesses (2 Samuel 13:18).

The rabbis in Tanhuma Vayeitzei8 go so far as to suggest that Joseph was meant to have been born a girl. As part of a discussion of whether God answers human prayers with respect to the gender of a fetus, the midrash relates that Leah, "foresaw in a dream that Jacob would ultimately have twelve sons. Since she had already given birth to six sons, and was pregnant with her seventh child, and the two handmaidens had each borne two sons, making ten sons in all, Leah arose and pleaded with the Holy One," and asked for a girl "so that Rachel could at least bear as many sons as their handmaidens." The midrash continues, saying God "hearkened to her prayer and converted the fetus in her womb into a female, as it is said: And afterwards she bore a daughter and called her Dinah (Genesis 30:21)."

The implication of this midrash is that out of extraordinary concern for her sister, Leah prayed for the (preferred) male fetus in her womb to be swapped with a female, so that Rachel's baby could instead be born a son: Joseph.

In her 1983 poem, "And She Is Joseph," contemporary Israeli poet Nuri Zarchi (b. 1941) calls to mind this midrash. but rejects the idea that this gender swap actually occurred. Instead, she imagines that Rachel gave birth to a daughter, whom she disguises as a boy and names Joseph:

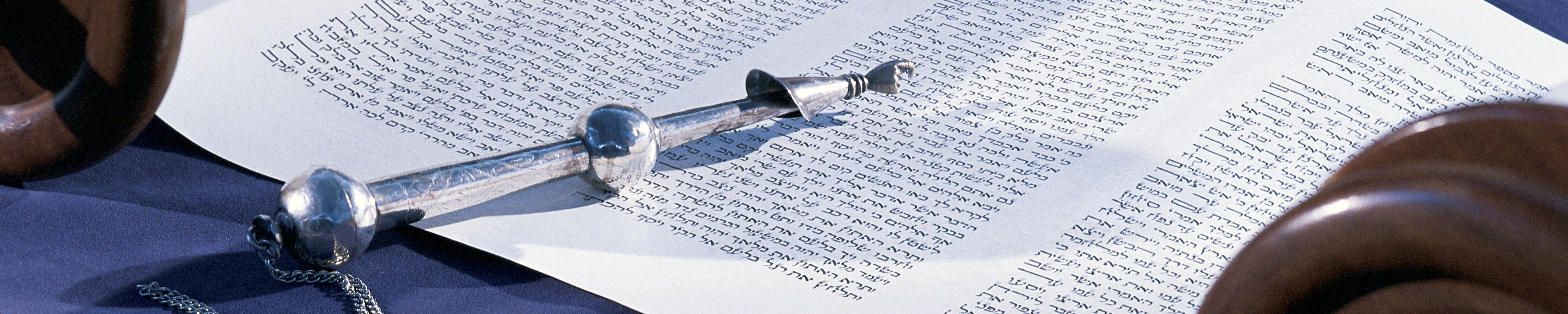

And She Is Joseph Rachel sits in the tent and gathers each curl closer to hide them under the silken cap of her little daughter Joseph, because if you wanted a son and your time was running out, what else would you do but lie to alter the will of God. The little one sits in the tent in a coat of colored stripes. Out in the open, a boy, But in secret, a girl. And now the whole world knows That her disgrace has been removed. Rachel bore an heir for his father and she is her daughter. And the mother stares at her daughter's hair Reads the future in her dark hair dreams will cast you into a pit, and from there, to a foreign court. The little girl sits in the tent, she hears her mother's words, and she's gripped by a spell, and she is gripped by fear, while Rachel continues, stunned, the blows do not cease: you will be locked in prison and be freed once again by dreams. Dreams will save you, daughter, will cast you in a pit. But Rachel's days are too short to solve the riddle of her daughter. The little girl sits in the tent, holds her breath and listens. Out in the open, a boy, But in secret, a girl. | והיא יוסף יוֹשֶבֶת רָחֵל בּאהֶל קְוֻצַּת שְֹעַר בִּתָּהּ הַקּטַנָה הִיא יוֹסֵף לְהַחְבִּיא תַּחַת כִּפַּת מֶשִֹי אֶת שְֹעַר בִּתָּהּ הקְּטַנָה הִיא יוֹסֵף כִּי אִם רָצִית בְּיֶלֶד וְיָמַיִךְ קְרֵבִים לִנְטוֹת מַה יַּעֲשֶֹה מִלְּבַד שֶקֶר אֶת רְצוֹן הָאֵל לְהַטּוֹת יוֹשֶבֶת הַקְטַנָה בָּאֹהֶל בִּכְתֹנֶת פָּסִים מְצֻיָּרה וּבַנִגְלָה הִיא נַעַר וּבַנִסְתָּר נַעֲרָה עַכֹשָיו כָּל הָעוֹלָם יוֹדֵעַ כִּי נֶאֱסְפָה חֶרְפָּתָהּ יָלְדָה רָחֵל בֵּן יוֹרֵֹש לְאָבִיו והִיא בִּתָּהּ וּמַבּיטָה הָאֵם בִֹּשְעַר הַבַּת עָתִיד קוֹרֵאת בּאֹפֶל שֹעָרָהּ הַחֲלוֹמוֹת בִּתִּי יַפִּילוּךְ לַבּוֹר וּמִֹשַם לְחָצֵר זָרָה. יוֹשֶבֶת הַקְטַנָה בָּאֹהֶל שֹוֹמַעַת אֶת דְּבַר אִמַּהּ והִיא אֲחוּזַת קֶסֶם והִיא אֲחוּזַת אֵימָה ורָחֵל מַמְֹשִיכָה נִרְעֶֹשֶת לֹא תַּמּוּ הַמּהֲלוּמוֹת בְּבֵית כֶּלֶא תֵּחָֹבְֹשִי וְתֵחָלְצִי שוּב מִידֵי חֲלוֹמוֹת חֲלוֹמוֹת יַצּילוּךְ בִּתִּי חֲלוֹמוֹת יַפִּילוּךְ לְבוֹר וְרָחֵל יָמֶיהָ קְצָרִים מִכְדֵי סוֹד בִּתָּהּ לִפְתֹּר יוֹשֶבֶת הַקְטַנָה בָּאֹהֶל מַקְֹשיבָה בִּנְֹשִימָה עֲצוּרָה וּבַנִגְלָה הִיא נַעַר וּבַנִסְתָּר נַעֲרָה. |

Early on in Parashat Vayeishev (Genesis 37:2), Joseph is described in grammatically anomalous fashion as "vehu na'ar et b'nei Bilhah ve'et b'nei Zilpah" - and he was a lad with the sons of Bilhah and Zilpah. In an endeavor to understand the phrase, "vehu na'ar et," another midrash (Genesis Rabbah 84:7) asserts that Joseph would act in a feminine way (ma'aseh na'arot) by penciling his eyes, curling his hair, and lifting his heel.

Zarchi's poem, like the above midrash, is a fantasy of gender impersonation and of exceeding ready-made, gender categories, in which the biblical Joseph is somehow both na'arand a (closeted) na'arah.This feminine or multi-gendered Joseph reflects a (20th century) feminist desire for greater access and representation, a desire to populate the biblical family with more girls and genders. The poem also acknowledges the grim reality that had Joseph been a girl, she would surely have been perceived as lesser. She might even have suffered a tragic fate similar to that of Dinah, the one daughter of Jacob mentioned in the biblical narrative.

The only way in this context for a daughter to get respect is to pretend to be a boy. The midrash from Tanhuma quoted above imagines two sisters who were otherwise rivals cooperating in the distribution of sons among them-collaborating against their own feminine interests. Zarchi's poem, by contrast, has Rachel give birth to the daughter she was meant to have all along. Still, Rachel yearns for her daughter to have the status and opportunities that a male child affords both mother and child. Rachel thus resolves to lie and have her child be both daughter and son-to subvert biological necessity by impersonating masculinity in public and maintaining her feminine identity in private. Note how the poem stages this drama of impersonation in a tent and marks it through Rachel's act of hiding Joseph's hair under a silken cap, a scene that recalls Rachel sitting in her tent and hiding the idols (teraphim) that she had stolen from her father in Genesis 31.

The great attention given in the poem to hair-the word se'aris repeated four times- recalls Jacob's impersonation of Esau's masculinity in Genesis 27 by dressing up his arms in goat hair, as well as the brothers' staging of Joseph's death by slaughtering a "se'ir izim." (a goat kid, Genesis 37:31). Both these instances of feigned identity in the Bible give rise to danger and pain, suggesting that this impersonation, too, will carry distinct perils.

Zarchi's portrayal of the young Joseph sitting in her tent decked or "drawn" (metzuyarah) in the "kutonet passim," suggest that Joseph's identity is being artistically sketched by his/her mother, and that Rachel also teaches her child the language of dreams and their interpretation. Rachel's life proves to be too short, however, to offer complete tutelage or interpretation of the riddle that that will be Joseph's life.

Much, then, remains in suspense. Will Joseph be forever closeted? Like the biblical Joseph, who finally unmasks himself to his brothers in Genesis 45:3, will this female Joseph eventually unmask herself as a woman or someone between genders and categories? Will the death of Rachel, who initiated the masquerade, allow for some other truth to emerge? Vayeishev marks the beginning of a gripping extended narrative cycle.

The young female Joseph of this poem listens to her mother's predictions and instructions with bated breath, as do we at the end of this parashah. We await the fate of this exceptional girl trying to play the role of a boy in a world and family that, for many years to come, will refuse to accept her as she is and allow her to assume her destined leadership position.