Focal Point

"Therefore, I pray, let my Lord's forbearance be great, as You have declared, saying, 'Adonai, slow to anger and abounding in kindness; forgiving iniquity and transgression; yet not remitting all punishment, but visiting the iniquity of fathers upon children, upon the third and fourth generations.' Pardon, I pray, the iniquity of this people according to Your great kindness, as You have forgiven this people ever since Egypt." And Adonai said, "I pardon, as you have asked." (Numbers 14:17-20)

D'var Torah

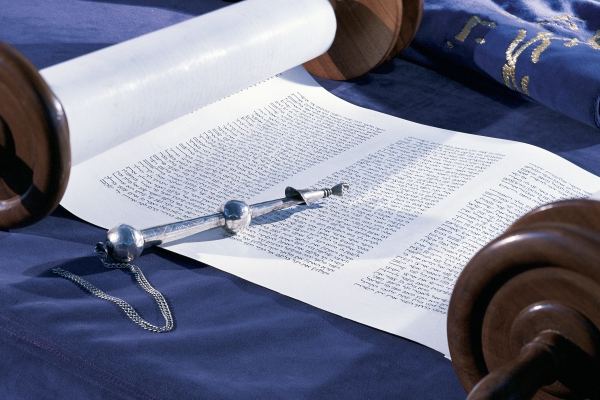

The concept of gaining God's forgiveness from sin, which we ask on Yom Kippur, hearkens back to the Exodus story of the Golden Calf. At least, so I thought. Yet, upon reading Parashat Sh'lach L'cha, I see that the Yom Kippur liturgy—specifically that having to do with God's granting pardon from sin—comes from this portion in Numbers.

The popular account of the origins of God's forgiveness on Yom Kippur comes from the story of the Golden Calf. We read that Moses pleads to God to spare the people after they sin and build the idol. And finally, after much such pleading by Moses, God pardons them and adopts a new covenant (Exodus 34:10). Pardon from sin is God's response to Moses' plea for forgiveness, and thus it is the basis we use to ask for atonement on Yom Kippur. But after comparing the Exodus text (Exodus 34:9) and the text from Sh'lach L'cha, it appears that forgiveness—God's pardon, which we recite several times on Yom Kippur (Numbers 14:19-20)—actually comes from the sin of the people who turn against God after hearing the negative report of the spies in the wilderness.

Moses sends twelve spies to bring back intelligence from the land of Canaan. Ten spies report that what lies ahead is not a pretty sight. "The country that we traversed and scouted is one that devours its settlers." (Numbers 13:32) Upon hearing this news, the community rebels against Moses and God, saying, "It would be better for us to go back to Egypt." (Numbers 14:3)

According to God, the people are sinners for not having faith in God despite all the signs and miracles God has performed on their journey thus far. God is ready to "strike them with pestilence and disown them" (Numbers 14:12) before Moses pleads to God that the Almighty should not rush to judgment. "Adonai, slow to anger and abounding in kindness; forgiving iniquity and transgression; yet not remitting all punishment." (Numbers 14:18) Moses reminds God that they had been down this road before. "Remember the Golden Calf incident, God?" Moses might have been thinking. "God, pardon us as You did at Mount Sinai." And God pardons the community using the words that we now repeat three times following the chanting of Kol Nidrei: "Vayomeir Adonai, salachti kidvarecha [And Adonai said: I have pardoned in response to your plea]." (Numbers 14:20 and Gates of Repentance, p. 253)

Moses' plea to God includes a recounting of God's attributes of mercy, which Moses learned from God at Mount Sinai. God expects Moses to retell those thirteen attributes to the people, especially in times of distress. In Exodus, Moses discovers those attributes to be that God is "compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness to the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; yet God does not remit all punishment, but visits the iniquity of parents upon children and children's children, upon the third and fourth generations." (Exodus 34:6-7) But in Sh'lach L'cha, Moses reorders God's attributes as "slow to anger and abounding in kindness; forgiving iniquity and transgression; yet not remitting all punishment, but visiting the iniquity of fathers upon children, upon the third and fourth generations." (Numbers 14:18) In so doing, Moses leaves out seven of God's attributes, including compassion, graciousness, and forgiving of sin. In addition, he begins with "slow to anger." Why is this so?

Rabbi Emanuel Levy of Britain's Palmer's Green and Southgate Synagogue, in an essay on this subject (Daf Hashavua, BRIJNET: The British Jewish Network, the United Synagogue of London, 1996) wrote that Moses leaves out these words because the sin of the people in Sh'lach L'cha is far greater than the sin they had committed regarding the Golden Calf. Rabbi Levy cites Rambam in saying that the sin was so great, God could not completely forgive the people. Therefore, Moses tries to appeal to God's attribute of "slow to anger" in his plea for God to have mercy on the people. According to Levy and Rambam, when God says, "I have pardoned according to your word," it really means "I have pardoned in accordance with Moses' plea for delayed anger."

Would God have pardoned the people anyway, even without Moses' appeal for delayed anger? Levy thinks so, citing the text, which says salachti—the past tense of "pardon"—perhaps to indicate that God had already pardoned the people but was waiting for Moses' plea. It was a test of Moses' faith, just as the true basis of the atonement we ask for on Yom Kippur today is that of being granted God's pardon for the sin of not having faith in God.

By the way. . .

- No sin is too big for God to pardon, and none is too small for habit to magnify. (Bachya ibn Pakuda, quoted in Reaching for Holiness: A Program for S'lichot, New York: UAHC, 2000)

- Rabbi Elazar ben Y'hudah taught: "The most beautiful thing a person can do is to forgive."(Harvey Fields, A Torah Commentary for Our Times, New York: UAHC Press, 1990)

- [In Louis Lewandowski's musical composition of Numbers 14:20, the text is set three times:] "Vayomeir Adonai, salachti kidvarecha; vayomeir Adonai, salachti kidvarecha: vayomeir Adonai, salachti kidvarecha." (And Adonai said, "I pardon, as you have asked.")

Your Guide

- The quote from Bachya urges us to think about our actions. But if God will pardon us for every sin, why should we even try not to sin?

- We are taught that God pardons us for our sins against God. How does Rabbi Elazar ben Y'hudah remind us that it is up to us to ask forgiveness directly from someone we have hurt?

- Why is the Yom Kippur prayer Vayomeir Adonai repeated three times in most musical settings of the text?

Sh'lach L'cha, Numbers 13:1–15:41

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 1,107–1,122; Revised Edition, pp. 977–997;

The Torah: A Women's Commentary, pp. 869–892

Explore Jewish Life and Get Inspired

Subscribe for Emails