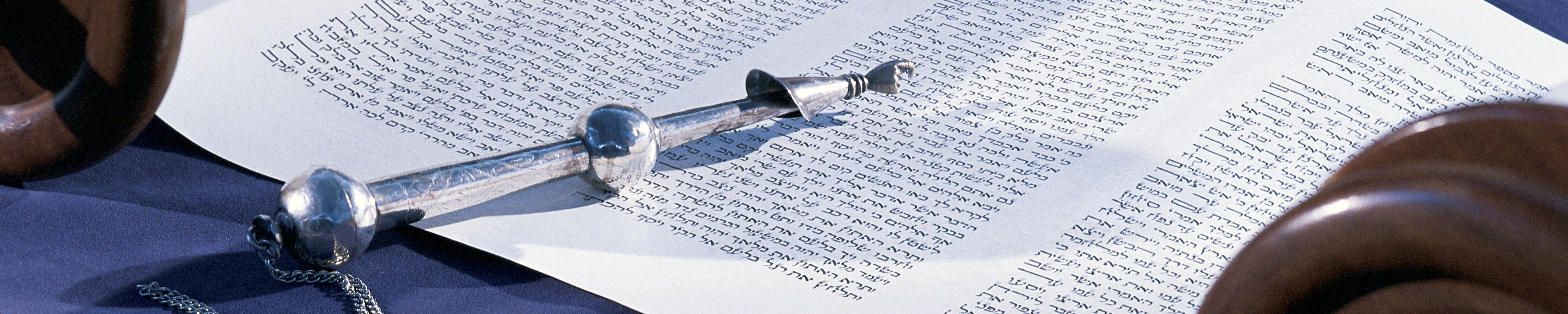

What was the Tachash?

Certain words in the Bible are relatively easy to decipher, and their meanings have been relatively consistent and well preserved since ancient times; others are a bit more opaque, their original significance unclear. Indeed, the most frequent footnote in the Jewish Publication Society's 1985 biblical translation is "meaning of Hebrew uncertain," instilling in readers a sense of humility and perspective.

One of these words makes an appearance in the enumeration of materials used in constructing the Tabernacle: tachash (Exodus 35:7). Sandwiched between "ram skins" and "acacia wood," we have little certainty about what it is beyond that context.

This, of course, leads to some fantastic speculation and wildly divergent interpretations. among both modern and ancient sources.

Contemporary scholars and translators are at odds. Modern research believes that tachash refers to leather prepared in a specific way, with cognates from Egyptian ("soft-dressed skin") and Assyrian ("sheepskin"). Several translations follow this approach. Everett Fox brings it into English as "tanned leather," while the Birnbaum Chumash has "fine leather," indicating that tachash is the result of a specific procedure and a particular type of skin or leather.

The early rabbis are similarly in conflict. Shabbat 28b of the Babylonian Talmud has an extensive discussion about the tachash's identity:

The tachash that existed in the days of Moses was a creature unto itself, and the Sages did not determine whether it was a type of undomesticated animal or a type of domesticated animal. And it had a single horn on its forehead, and this tachash happened to come to Moses for the moment while the Tabernacle was being built, and he made the covering for the Tabernacle from it. And from then on, the tachash was suppressed and is no longer found.

In other words, the tachash was a singular creature that served for this one moment: the building of the Tabernacle.

From other sources, we draw additional (sometimes divergent) attributes. From the Targum, an early Aramaic version of the Bible, the tachash was multicoloured and took pride in its rainbow-like appearance. The Talmud alludes to an unresolved debate over whether the tachash was domesticated or wild. Ramban suggests that the tachash's skin was waterproof and was used to protect the Tabernacle from rain. Other commentators are impressed by its immense size - what other creature was sufficiently large that its skin could be used to make curtains thirty cubits long?

This takes us through a sampling of the land animals and products that have been linked to the tachash. There's an entire other school of thought that names the tachash as some sort of sea creature. The classical Arabic tuchas ("dolphin" or "dugong") hints at this, but recent opinion favours identification with an extinct species of sea cow. Indeed, an abundance of English bibles today use "dolphin skins" or something similar. Personally, I like to combine the sea creature logic with the single-horned description in the Talmud, imagining the tachash as a narwhal.

There are plenty of additional references to and descriptions of the tachash, many of them mutually exclusive: was it domesticated or wild, a land or sea creature, kosher or not? Did it have a horn? What colour(s) was it? Resolution might be elusive here, but I want to zoom out to make a broader point:

Many of our readings and interpretations of biblical text are grounded in uncertainty. Even as some can be cited and spoken of with justifiable self-confidence, others demand to be regarded with humility, a posture of openness, and an appreciation for the multiplicity of meanings they may carry. Moreover, the tendency to divide the world into binaries - kosher or unkosher, domesticated or wild - can be helpful, but may also be inapt and misleading. We are often better off leaning into the ambiguity and gray areas. As we make our way through Jewish texts, we should discern when each of these approaches and distinctions is appropriate and ensure we treat them in a fitting manner.