In March of 2019, my beloved father was hit by a truck and killed. At the end of January 2020, five days before the eleven-month period of my daily Kaddish recitation for Dad was supposed to end, my mother died. Six weeks later, the coronavirus engulfed the world, subsuming my personal grief in a worldwide drama. Early in this saga, as an extension of my months of Kaddish recitation, I adopted a spiritual/pedagogical discipline based on my area of expertise: modern Hebrew literature. Each week, I chose and translated a different Hebrew poem related to prayer and offered my commentary as a weekly d'var Torah, which I delivered after Tuesday morning services and shared with readers via email. I dubbed this practice "Shir Ḥadash shel Yom" (New Poem of the Day). These teachings coalesced into a Kaddish/COVID memoir, Going Out with Knots: My Two Kaddish / COVID Years with Hebrew Poetry, which will be published in 2025 through the Jewish Publication Society.

The Shir Ḥadash project has continued for exactly five years, having begun immediately after the 2019 High Holidays. To mark this anniversary, I've decided to base my weekly commentaries on a relevant modern Hebrew poem.

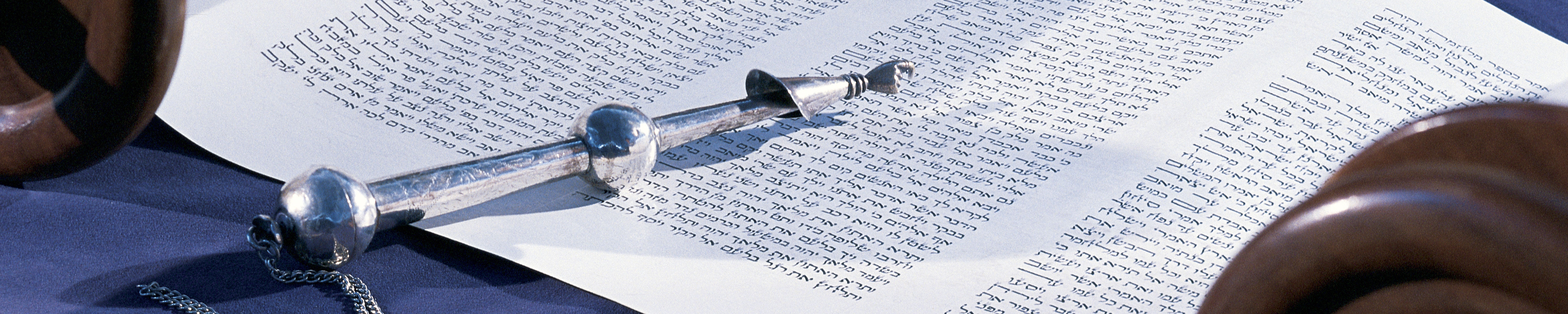

This week, I am reflecting on a poem by Rivka Miriam (penname of Rivka Miriam Rochman, b. 1952). Rivka Miriam is an Israeli poet and artist who has been instrumental in the Jewish secular religious renewal movement in Israel. Her liturgical poetry is part of an effort to bring a new secular, liberal, Israeli voice to Torah study. This 1982 poem, "In the Beginning God Created," based on first verse of the Bible, depicts the creation not just of a physical but also a spiritual world.

In the Beginning God Created By Rivka Miriam | |

| In the beginning God created the heavens that aren't actually and the earth that wants to touch them. In the beginning God created threads stretched out between them - between the heavens that aren't actually and the earth that cries out for salvation, And God fashioned humankind Such that a person is a prayer and is a thread touching what is not with a touch of tenderness and subtlety. | בְּרֵאשִׁית בָּרָא אֱלֹהִים |

The poem first responds to the head-centered nature of the word "b'reishit" (בראשית), often translated as "In the beginning," but which also contains the Hebrew word for head, "rosh" (ראש). The creation account that follows this verse exemplifies a form of creation that begins or comes from God's head.

Before the six-day sequence comes the general statement in verse 1 about God having created, bara (ברא), a unique verb connoting divine creation, which also appears at the head of the word b'reishit (בראשית), the heavens and the earth (et ha-shamayim ve'et ha'aretz). Rivka Miriam's radical poetic commentary on this verse supplants the word aretz (earth, land) with the more human/Adam-centered " adamah," imagining the earth as yearning to touch "the heavens that aren't actually." These heavens symbolize a spiritual, transcendental realm and a play on the word "sham," Hebrew for "over there." The suffix "ayim" indicates a pair. This double-over-there precedes earth and in some fundamental way is beyond it. Yet these same heavens distinguish for all time the earthling, Adam/ish, whom Miriam envisions as "a prayer and a thread / touching what is not / with a touch of tenderness and subtlety."

Rivka Miriam's poem thus depicts the creation of prayer as part of Earth and Earthling's design. Both Adam and adamah are portrayed as being engaged in prayer.

But what does it mean that the heavens, "aren't actually?" Is Miriam suggesting that the earth and its most sapient creatures are caught in an illusion, reaching out to something or Someone that doesn't exist?

In his book, "Creator, Are You Listening?", scholar David Jacobson suggests that "humanity appears here to be well-meaning, but also self-deceiving, as it undertakes an attempt to reach out for contact with the divine that is doomed to fail."

I'd like to offer a more optimistic reading, however, of the poem and of prayer by exploring two distinct word choices Rivka Miriam makes. Typically, words like einam/einenu (aren't/isn't) serve to negate something, but the word einenu also appears in the Bible to refer someone who is currently missing but may yet return. In Genesis 37:30, Reuben returns to the pit where the brothers abandoned Joseph but discovers that he is einenu (gone). Later, the brothers and their father are all reunited in Egypt. Similarly, in Jeremiah 31:15-16, the matriarch Rachel is seen weeping in Ramah over her exiled son(s), " ki einenu" (for he is gone). The singular form perhaps hints at the beloved status of Joseph, Rachel's temporarily missing son. Immediately, God reassures Rachel that all her sons will return. Rivka Miriam's image of touching something she'einenu thus points not to something that doesn't exist, but rather that is currently missing while remaining within the realm of hope.

This notion of hope is underscored by the word chut (חוט), meaning thread. On the surface, chut seems flimsy, but it appears throughout the Bible and rabbinic literature in more substantial contexts. In Joshua 2:18, Rahab ensures the safety of her family by placing a tikvat cḥut hashani (a length of crimson cord/thread) in her window. Here, the association of the word chutwith tikvah creates the impression of a durable thread of hope. Similarly, Song of Songs 4:3 describes the Shulamite's lips as a chut hashani (a crimson thread), endowing the thread with the power of speech and love, two central elements of Jewish prayer.

Rivka Miriam's depiction of Adam/ish (humanity) as a tefilah (prayer) and chut (thread) reaching out to the heavens with softness and dakut (subtlety or delicacy) brings to mind God's revelation to Elijah in 2 Kings 19:12 in the form of a kol demamah dakah (a still, small voice). All this suggests the possibility, however subtle and elusive, that somewhere, sometimes, God is answering us; and that the possibility of this dialogue came into being concomitant with the creation of the whole wide world.