Freedom is an ideal for humanity that we constantly strive to reach. In 1986, Elie Wiesel (z”l), on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize, said:

“As long as one dissident is in prison, our freedom will not be true. As long as one child is hungry, our life will be filled with anguish and shame. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.”1

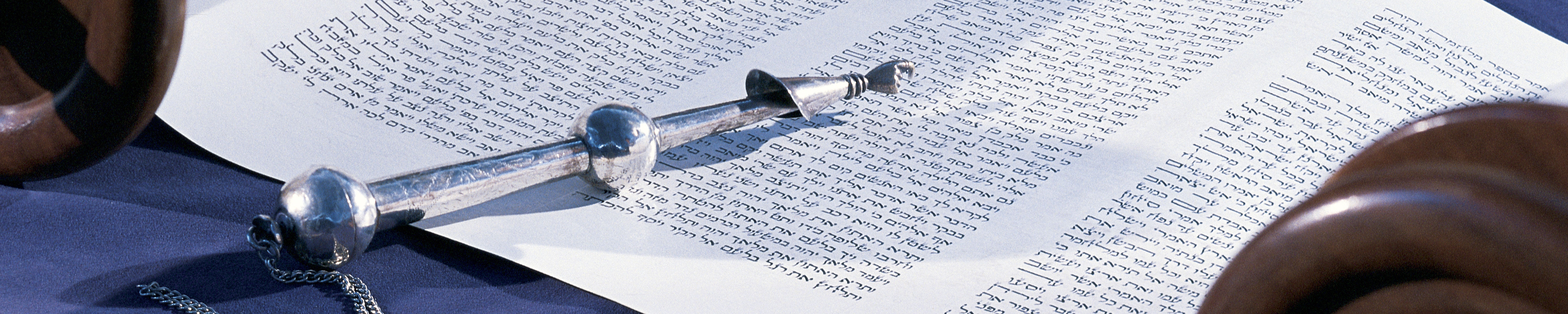

To be truly free is to possess the human power to choose to live by the rules that bind us. To be free of any rules is to be lawless; therefore, the rules that bind us should, at best, hold us fast to principles and ethics that lead us to our greatest human potential. For Jews, the rules that bind us are Torah. Milton Steinberg, writing for the Traditionalist and Modernist, as he categorized them (us), explained:

“Torah becomes everything which has its roots in the Torah-Book, which is consistent with its outlook, which draws forth its implications, and which realizes it potentialities. Torah, in sum, is all the vastness and variety of the Jewish tradition.”2

In Torah this week we read B’har/B’chukotai, a double portion that brings us to the end of Leviticus. In B’har, we find the famous verse, “You shall proclaim release throughout the land for all its inhabitants” (Leviticus 25:10). Inscribed on the Liberty Bell with the word “freedom” instead of “release,” it, nevertheless, connotes the expectation that humanity thrives in places where freedom from hunger, redemption from bondage of any form, and release from tribulations unleash our greatest human potential. Freedom from toil reflected in the weekly Sabbath and cyclical Jubilee year, were chief among the commandments that the Israelites would observe in order to know God’s greatest blessings.

Not unlike our Israelite ancestors, we are also bound to the covenant of teachings and laws within which we seek God’s favor and blessings over the course of our own lifetime. In B’chukotai (Leviticus 26:3ff) we read, “If you follow my laws and faithfully observe my commandments...” then God will cause you to prosper and be blessed.

Our Sages responded. They knew well that prosperity and blessings flowed from God, but they also observed suffering despite faithfulness to God’s covenant. They cited Job, who suffered blamelessly. We find, “His days are determined; You know the number of his months; You have set him limits that he cannot pass” (Job 14:5). (Midrash Tanchuma, B’chukotai 1).3 In citing Job, they raised the question: what, if anything, would forestall the end of our days if all was, indeed, foreseen, and if our days were limited even when we did God’s commandments?

Our Sages affirmed their faith that all life is a gift from God. They embraced what was revealed to them by God, and what they could do with what was revealed to them. Rather than be disillusioned about what remained concealed from them, they grasped for opportunities to do mitzvot, to respond to God’s command, and to know that, even when judgment came instead of mercy, it was God’s will, too. They cited God’s goodness to King Solomon, even above that which God gave to his father, David, “And I grant you also what you didn’t ask for, both riches and glory all your life … and I will further grant you long life, if you will walk in My ways and observe My laws and commandments…” (I Kings 3:13).4

Leviticus ends with a list of curses. “But if you don’t obey me…” (Leviticus 26:14), begins the list of ways that God will spurn the Israelites if they fail to keep faith. Today, biblical injunctions and admonishments have lost their sway over us, whether we’re Traditionalist or Modernists. Instead, we’ve learned from rabbis like Harold Kushner, who taught us in his ubiquitous book, “When Bad Things Happen to Good People,” that instead of expecting from God what we thought we deserved, God also grants what we didn’t know was available in addition. Life is hard, and when (not why) it hurts, we can seek and find compassion, unconditional love, and lessons for living. They are God’s “riches and glory,” too.

In “Gates of Prayer” we read, “Just because we are human, we are prisoners of the years. Yet that very prison is the room of discipline in which we, driven by the urgency of time, create.”5 Freedom from that prison doesn’t come from seeking immortality; rather, freedom continues to be the privilege to choose the rules that will bind us. As Jews, we still choose to bind ourselves to the b’rit, the “covenant” that God made with our ancestors and with us for “our life and the length of our days” (Deuteronomy 30:20).

Now, at the end of the Book of Leviticus, we say, chazak, chazak, v’nitchazeik, “be strong, be strong, and let us strengthen each other.” As one book closes and another book opens, our studies of the Bible continue. We have been taught to learn so that we may teach. Let us be teachers of our sacred texts that the world may hear our words, benefit from our deeds, and be inspired by our hopes.

Thank you for joining me in the Book of Leviticus. Chazak, chazak, v’nitchazeik!

1 Elie Wiesel, acceptance speech, Nobel Peace Prize, Oslo, December 10, 1986

2 Milton Steinberg, “Basic Judaism” (NY: Harvest, 1947], p. 22)

3 Midrash Tanchuma, Parashat B’chukotai 1

4 Ibid.

5 Gates of Prayer (New York: CCAR Press), p. 625

Rabbi David A. Lyon is Senior Rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel in Houston, TX. Rabbi Lyon serves on the Board of Trustees of the Central Conference of American Rabbis and chairs its professional development committee. He can be heard on “iHeart-Radio” KODA 99.1 FM, every Sunday at 6:45 a.m. CT, and is the author of God of Me: Imagining God Throughout Your Lifetime (Jewish Lights 2011) available on Amazon.com.

Yasher koach to my colleague, Rabbi David Lyon, on his insightful comments on this week’s parashah, B’har/B’chukotai. I believe he begins to explore the distinction between the ideas of “freedom within” and “freedom from.” It is here where I believe that Judaism embraces the latter ethic as a driving force in making sacred and informed decisions. The great sage Maimonides taught that all is foreseen, yet freewill is given (see Mishneh Torah, Hilchot T’shuvah, chapter 5). Leviticus and especially the last few chapters, lays out for us the opportunities and challenges we have to choose to live a sacred life.

Yasher koach to my colleague, Rabbi David Lyon, on his insightful comments on this week’s parashah, B’har/B’chukotai. I believe he begins to explore the distinction between the ideas of “freedom within” and “freedom from.” It is here where I believe that Judaism embraces the latter ethic as a driving force in making sacred and informed decisions. The great sage Maimonides taught that all is foreseen, yet freewill is given (see Mishneh Torah, Hilchot T’shuvah, chapter 5). Leviticus and especially the last few chapters, lays out for us the opportunities and challenges we have to choose to live a sacred life.

- Freedom within: Leviticus 26:3 begins; “If you follow My laws and faithfully observe My commandments.” The Holy and Blessed One sets out a series of blessings that will emerge thought our covenantal choices. Verse 26:12 concludes with; “I (God) will be ever present in your midst; I will be your God, and you shall be My people.” When we live within a covenantal contract with God, we find in our daily journey a life filled with blessings and opportunities for elevating our soul.

- Freedon from: And the opposite holds true if we choose to free ourselves from the Divine covenant. In Leviticus 26:15-16 we read: “if you reject My laws and spurn My rules, so that you do not observe all My commandments and you break My covenant, I in turn will do this to you: I will wreak misery upon you…. ” Setting aside for a moment the absolutes that Leviticus presents, it does suggest the importance of keiruv, “coming closer.” Freedom from the covenant or sacred choices that Judaism embraces puts a barrier between us and holiness.

Maimonides understood this choice implicitly when he presented us with the challenge to choose. Of course, he embraced more fully the idea of choosing within a system of sacred choices rather than abandoning covenant completely. When he states that “all is foreseen” he elevates the idea that impact of the choices we make (whether within or from), will lead to a defined point already known.

As Rabbi Lyon’s draws his commentary to close, he reminds us that our freedom within a covenantal system empowers us to make sacred choices, to make our lives more sacred and to live our days soulfully connected to the Holy and Blessed One. If we engage in this covenantal encounter, if we follow the teachings, if we listen to our hearts, if we trust in the world, if we sense the power in the unknown and unseen, then God will be our partner and guide. That which is weighty will be made light, that which is empty will be made full, he who is hungry will be sated, she who is needy will become rich. All we need to do is stand up and be counted among God’s partners and live the covenant. That is the b’rit to which we all want to belong.

Rabbi David A. Lipper is the rabbi at Temple B’nai Torah in Bellevue, WA.

B’har/B’chukotai, Leviticus 25:1-27:34

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 940-970; Revised Edition, pp. 849-879

The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, pp. 747-786

Haftarah, Jeremiah 16:19-17:14

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 1,006-1,008; Revised Edition, pp. 880-882