After the individual sagas that comprise so much of Genesis — Joseph’s story alone consumes the better part of 19 chapters — the speed at which the Israelites’ fortune reverses at the beginning of Exodus is stunning. And all it takes is one verse.

In this week’s portion, Parashat Sh’mot, we read:

“A new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.” (Ex.1:8)

And just like that, everything changes. The Israelites had been numerous ever since Joseph’s brothers and their households arrived in Egypt. But now, their numbers are perceived as a threat. They had been shepherds for generations; their flocks and herds thriving in harmony with the fertile land. But now they are made to build garrison cities from mortar and brick; their labor forced and their lives embittered by overseers and taskmasters.

So how will their fortunes reverse once again? Coming chapters will describe the marvels and wonders that finally convince Pharaoh to let the enslaved Israelites go free. But two separate encounters in this week’s portion set the journey to freedom in motion. Two individuals in particular who otherwise live in comfort witness the suffering and the plight of Israel. Whereas this pharaoh has forgotten Joseph, they take it upon themselves to know his descendants. And once they do, they begin their journeys from being part of the problem to becoming part of its solution, as we read:

“The daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe in the Nile.” (Ex. 2:5)

When Pharaoh’s daughter “came down” to the Nile, she descended in more ways than one. Physically, and humbly, she left the gleaming, looming edifice of the palace to walk down to the river. In terms of social standing, she took her place as one of many on the bank of the Nile, the lifeblood to all of Egypt that sustained both royal and commoner, taskmaster and enslaved servant alike. Rabbi Yochanan, in the name of Rabbi Shimon, suggests a pointed purpose for her descent: “She came down to cleanse herself from the idolatry of her father” (Babylonian Talmud, Sotah 12b). In other words, she came to wash away the impurity she felt as a result of the Pharaoh’s unjust policies. And what did she discover when she descended from the palace and arrived at the bank of the Nile? She found a basket hidden amongst the reeds. She found a baby boy crying. She encountered suffering and despair. And she was moved; she took the child in as her own, and the boy grew up in the royal household. Later, we read:

“Some time after that, when Moses had grown up, he went out to his kinsfolk and witnessed their labors.” (Ex. 2:11)

Like his adoptive mother, Moses didn’t just hear or see news that traveled to him in the palace. He went out among the people and witnessed the ongoing experience of the enslaved Israelites. He got close enough to feel their suffering in his own gut. As the French Jewish scholar and philosopher André Neher wrote:

“Witnessing an injustice and degradation of another, Moses feels the blow dealt to the other as though it were directed against himself. Breaking through the selfishness of his own ego, he discovers his neighbor. It is this discovery that, in the last resort, brings about the Exodus. The estrangement between men [and women] has disappeared. ... Now all men [and women] are neighbors.” (Etz Hayim Torah and Commentary [Philadelphia: JPS, 2001], p. 324)

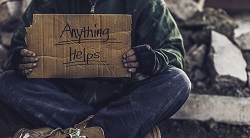

In modern times, civil rights attorney and social-justice champion Bryan Stevenson has worked as diligently as anyone to alleviate suffering in this generation. His motivation stems from the lived experiences of those with whom he sits face-to-face. Those experiences stem from the injustices they have been dealt by a legal system that is suppressing truth, persecuting children, failing those with mental illness, and rewarding wealth. What he describes as crucial to his own journey, he explains as absolutely essential for all us: We have to “get proximate” to those who are suffering — to the poor and vulnerable, the oppressed and weak. We have to get proximate to the injustices we are trying to correct and the people who are living and experiencing them in their daily lives. We have to come down to the water and go out among the people. We have to risk having our hearts moved.

This coming weekend, in the United States and in many of our congregations, we will remember the work of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. We will recall his inspiring speeches, the soaring rhetoric that lifted hearts and souls and, indeed, the general discourse about freedom and liberty. His most enduring quotations will be shared with reverence both in houses of worship and civic spaces. Yet the legacy of King’s deeds far exceeds that of his words. King got proximate with injustice. Though he had the ears of leaders in Washington, he went down to Montgomery and Selma and Memphis. He bore witness to the specificity of injustice: the exhaustion of those forced to schlep to the back of a bus; the degradation of exclusion from democracy by the denial of one’s right to vote; the dismissed humanity of a worker denied fair compensation, and made to risk his life under unsafe working conditions. King stood with the people. He marched, linked arms, and cast his lot with all of the people. And while there would be others who spoke truth to power, King, by being proximate to the lived experiences of those for whom he fought, conveyed the power of their truth.

As King said: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” How does it bend? Those who get proximate to suffering — from Pharaoh’s daughter and Moses to Bryan Stevenson and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. himself — are the ones who bend it.

Rabbi Stephanie M. Alexander is the senior rabbi at Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston, SC. She is a past-president and founding member of the Charleston Area Justice Ministry, a faith-based social justice organization of 29 diverse congregations.

I’m a middle-class Jewish kid from the suburbs of Chicago, raised with all the white privilege that ran rampant and quite unconscious in the 60s and 70s. My folks viewed the world and its burgeoning upheaval from a distance, shaking their heads in dismay over the war, the riots, the protests, trying to shield us kids from the worst of it.

I’m a middle-class Jewish kid from the suburbs of Chicago, raised with all the white privilege that ran rampant and quite unconscious in the 60s and 70s. My folks viewed the world and its burgeoning upheaval from a distance, shaking their heads in dismay over the war, the riots, the protests, trying to shield us kids from the worst of it.

When I was older and more involved in the world, I was taught that it was our job, as Jews, to fight for social justice. My real education on social justice and social action came from my temple youth group. We talked about anti-Semitism and its impact. We worried about the Middle East. We praised Dr. King and mourned his loss keenly.

Still, I learned the broad brushstrokes of activism and change from the safety of my distance. Looking back, my pursuit of social justice was loud and intellectual. I don’t know that it actually touched me. Sure, I was appalled that I had been alive when there were signs on drinking fountains that read, “Whites only.” I couldn’t believe there were quotas and cutoffs for schools and jobs and immigration. I believed the world worked just as we were taught in the history books that there was justice for all. “We, the People,” indeed. I was proud that I was raised colorblind (and religion-blind and sexual-orientation blind). But really, I was raised blind, as only the truly privileged can be.

Then, in the mid-80s, I quit graduate school and went to work for ACORN, a national poor people’s organization. I left my safe ivory towers for the neighborhoods and people that had, until then, been academic realities at best. I knew of them; I did not know them.

And what does this have to do with Sh’mot, this week’s parashah? As Rabbi Alexander has so eloquently described, like Pharaoh’s daughter, like Moshe, I finally stepped outside of my comfort zone — that safe, distant, not-touching space. I got proximate. I got down into the trenches and rolled up my sleeves to do the work that I had been taught was the real work of our lives.

Our text is so clear! Go to Leviticus 19, K’doshim — the Holiness Code, where the Eternal One tells Moses to tell the community, “You shall be holy, for I, the Eternal your God, am holy” (Lev. 19:1-2). That means, “When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall leave them [the fallen fruit and grain at the edges of your field] for the poor and the stranger” (Lev. 19:9). It also means, “The strangers who reside with you shall be to you as your citizens; you shall love each one as yourself” (Lev. 19:33). And read in Deuteronomy, where it tells us not to turn away from the poor among us but to open our hands, lend what is needed, and to leave part of our harvest for widows and orphans (Deut. 15:7; 26:12).

Defend the poor, the widow, and the orphan. Ensure fairness and justice for all, stranger and citizen alike. Feed the hungry, clothe the naked. Answer the need with an open hand and an open heart, not because of some hoped-for reward, but because we are commanded to do so — not just once, but again and again. And why? Because we are created b’tzelem ELohim, “in the image of God.” God tells us, again and again: be holy because I am holy.

Rabbi Alexander argues that we must get proximate, get close, but I think we are required to do something even more radical than that. The Mishnah tells us that whoever destroys a single life is considered by Scripture to have destroyed the whole world, and whoever saves a single life is considered by Scripture to have saved the whole world. (Mishnah, Sanhedrin 4:5)

We are one. If injustice happens to someone — whomever it is — it happens to me. Mishkan T’fillah, our siddur, says, “When will redemption come? When we grant everyone what we claim for ourselves” (p. 269). Where Torah commands “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Lev. 19:18), it should have continued, "because he [she/they] is you." Like Pharaoh’s daughter, like Moshe, like Dr. King — get close, get proximate! Get radical, and understand that there are no strangers, there is only us. Inspired by the prophets, I wrote this poem that remembers Elijah’s encounter with the “still, small voice” of the Eternal (I Kings 19:11-13) and Isaiah’s call that we, “Learn to do good: Devote yourselves to justice” ( Isaiah 1:17). Who knew that they too believed in getting proximate and beyond? The time for being idle has passed; it's time to move and change and grow — and heal.

There was no voice,

or perhaps a voiceless voice —

so soft, so small,

if could only be heard

just beyond the edges

of hearing.It sang anyway,

that voiceless voice.

It ran through my body

and burned my hands

that lay idle at my side.It drummed a beat

that moved my heart,

that moved my feet

in surprising syncopation.

Not a waltz,

nor a tango,

but my idle feet,

idle as my hands —

my idle feet

Moved.They danced with the

voice that was no voice

that had no sound,

but it sang in my heart

and burned my hands

and beat in steady rhythm

and so I danced.and sang the song

of the voiceless,

and stumbled on broken bits

of shattered tablets.(Stacey Zisook Robinson, “My Idle Feet Moved,” for Isaiah 1:17)

Stacey Zisook Robinson is a poet and essayist who lives in Chicago. She works as a Poet/Scholar-in-Residence, creating workshops to explore the connection between poetry, prayer and text. She blogs at, and is a regular contributor to kveller.com, the Reform Judaism blog and Ritual Well. Her book, Dancing in the Palm of God's Hand, was published in 2015, and her newest, a book of poetry, A Remembrance of Blue, was released in November 2017.

Sh’mot, Exodus 1:1−6:1

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 382−414; Revised Edition, pp. 343–374

The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, pp. 305–330

Haftarah, Isaiah 27:6–28:13; 29:22−23

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 692−695; Revised Edition, pp. 375−378